This year for Pollinator Week (6/17 – 6/23) we’re doing a 7-part series about native pollinators on Edisto Island!

We, as a civilization, need pollinators. They keep the gears of agricultural and ecosystem services turning behind the scenes, rendering an invaluable service to plants, which yield these values to us. Pollinators need our help. Thankfully, pollinators are everywhere and anyone can lend them a helping wherever they are.

Pollinators are a diverse group of animals adapted to a wide range on ecosystems, habitats, and environmental conditions. They’re able to fend for themselves and don’t need any special treatment as a whole. However, they are all being hit from every angle with overwhelming forces they can’t overcome on their own. The biggest threats to pollinators right now are misuse of insecticides and habitat loss. As an individual, these threats are easy to dissipate at the small scale. Don’t fog for mosquitos, don’t spray insecticides in your garden, leave leaf litter around the edge of your yard, create a brush pile, leave dead flower stems alone, don’t mow as often, and plant native plants where ever you can.

However, the biggest contributor to both these threats in the Lowcountry is suburban sprawl. The best way to curb sprawl is by supporting local land conservation efforts. Land conservation is what we do here at EIOLT. We protect dirt from destruction. We save special places for tomorrow. We humans rely on natural ecosystems and agricultural crops for food and natural resources. Food crops and natural ecosystems need pollinators. Pollinators need native plants. Native plants need soil. Soil is the land. In order to protect our native pollinators and safeguard our futures, we need to first protect the land that we all rely on. Protect places for plants, for pollinators, for people, for the future, forever. The work of the Edisto Island Open Land Trust protects the capacity of land to support pollinator habitat, our native plants, our wildlife, our natural resource economy, and the intrinsic beauty of Edisto Island. We need your help to conserve land, and everything that relies upon it. If you’re not a member already, please considering joining EIOLT and, if you are, thank you, sincerely, for all that do to protect the one-of-a-kind Edisto Island.

Pollinator Week 2024: Pollinator Plant Recommendations for Edisto Island

This year for Pollinator Week (6/17 – 6/23) we’re doing a 7-part series about native pollinators on Edisto Island!

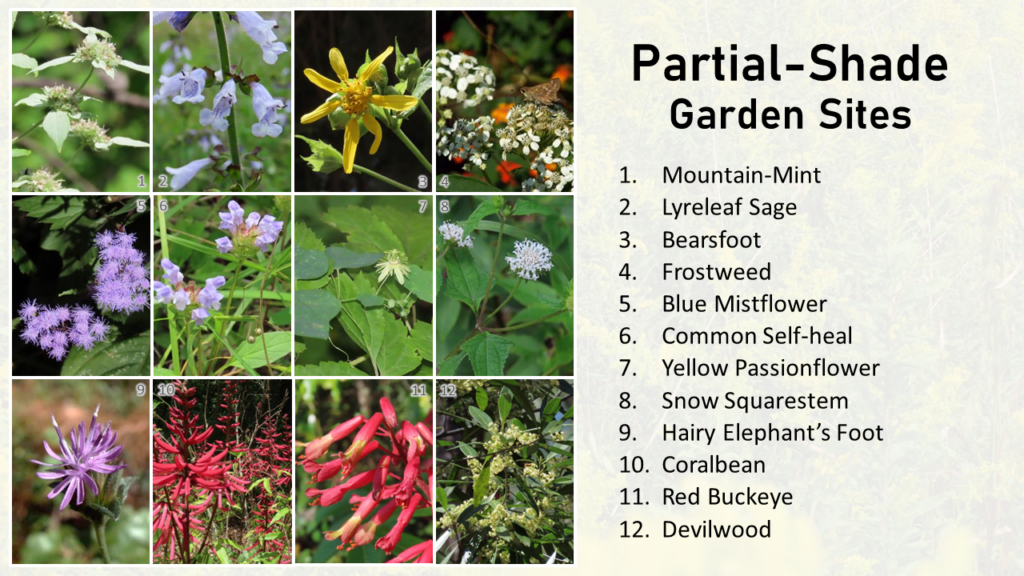

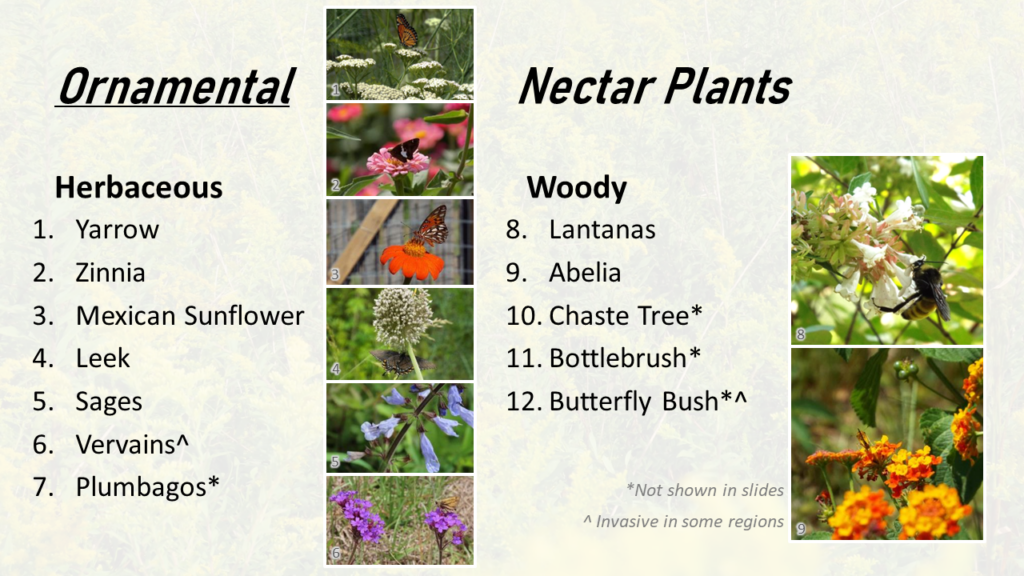

If you’re considering building a pollinator garden, bringing native plants into your yard, or managing land for pollinator habitat, you’re going to need to know which plants work best for Edisto Island. Here, we’re in the borderline subtropics of the Lowcountry, meaning many plant recommendations you’ll find online for the Southeast US often aren’t worth much of anything. However, lucky for you, I’ve spent the better part of the last decade planning, planting, and managing native plant gardens in the Edisto area. So, I’ve got a good handle on what works and what doesn’t here and I know the plants that are specialized to our unique sea island soils and climate. I also spent all of this spring building out a set of slides and a pollinator garden plant recommendation list focused on Edisto Island.

If you’d like to give them a gander, check out the link below:

These plant recommendations of mine are specifically focused on butterflies (because, as a butterfly researcher, I’m biased) but almost all are good for a wide range of our native pollinators. One thing I do want to stress is the importance of using native plants in your pollinator garden, yard, and lawn. Native pollinators are adapted to make use of native plants. Native plants are adapted to our local climate, soils, and wildlife. Native plants, pound for pound, will always be better for our native pollinators and wildlife than any exotic ornamental plant. Further, many ornamental plants, even the ornamental varieties of native plants, have been bred in such a way that they no longer provide all the benefits they should to pollinators. So, plant native and, if you can, plant local ecotypes of native plants. These plants will grow better, require less care, and provide the maximum benefit to our native pollinators and wildlife.

For further information, recommendations, and sources of native plants and seeds, you can also check out the SC Native Plant Society and Xerces Society, both linked below:

https://xerces.org/pollinator-conservation/native-plant-nursery-and-seed-directory

This year for Pollinator Week (6/17 – 6/23) we’re doing a 7-part series about native pollinators on Edisto Island!

If you want to go the extra mile to help our native pollinators, then you should consider planting a pollinator garden or, if you have a bit of acreage, managing a pollinator habitat. A pollinator garden has the expressed intent of maximizing its benefit to native pollinators. A pollinator garden should have the goal of becoming an island unto itself, a microcosm providing everything our pollinators need to flourish and persist or, at the least, a lot of what they need but aren’t getting from the surrounding landscape. To create a full-fledged and functional pollinator garden you need to provide 4 main features.

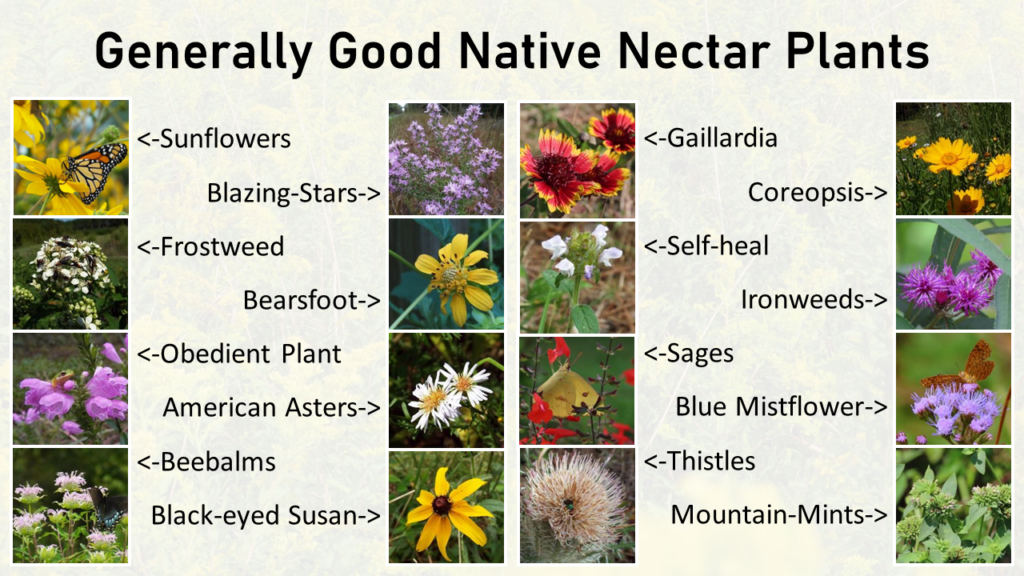

First, nectar plants. Nectar plants provide food for adult pollinators. You need nectar plants of all shapes, sizes, colors, and bloom times to attract the greatest diversity of pollinators. The broader your nectar plant selection, the more reliable a food source your garden will be for pollinators.

Second, pollen plants. These feed baby bees. Bees are the most efficient pollinators and are doing the heavy lifting elsewhere, outside of your garden. You want to make sure you’re also providing bees with ample pollen, in addition to nectar, to feed the next generation of bees all throughout the year. Our native bees come in all shapes and sizes, so a diversity of flower sizes and shapes is a must.

Third, host plants. Host plants are the nurseries for your butterflies, and moths, since their caterpillars eat plant vegetation. Many butterfly species can only eat a specific set of plants. If you want to maintain a diversity of butterflies in your garden, you need to supply the adults with nectar and the caterpillars with leaves. Subsequently, these caterpillars become food for pollinating wasps, who feed them to their own little ones.

Fourth, refuge and nesting habitat. Pollinators need places to hide, to rest, and to nest. Leaf litter, old flower stalks, bare soil, brush piles, and old logs all provide refuge habitat to certain types of pollinators during different stages of the life cycle. So, leaving a pollinator garden messy and debris untouched is often both the best thing for pollinators, and it’s as easy as doing nothing at all!

This week for Flora and Fauna Friday, we have a tropical butterfly with a transparent caterpillar, the Brazilian Skipper (Calpodes ethlius).

The Brazilian Skipper is large for a skipper, at about an inch-and-a-half in length with an elongated forewing. The underside of their wings is a golden-brown with four white cells, the technical term for spots, in a diagonal line towards the outer edge of their hindwing. From above, their wings are a dark brown towards the center with a half-dozen or so large, blocky white cells. Their eye is surrounded with a prominent white eye-ring. Overall a drab butterfly that’s a bit overgrown and with some anatomical quirks. Being a large skipper, Brazilian Skippers are strong and fast fliers, zipping around between flowers and perches. Their large size and an extra-long proboscis allows this butterfly to easily sip nectar from larger flowers, those usually reserved for acrobatic hummingbirds and spelunking bumblebees. Brazilian Skippers are mainly crepuscular, flying at dawn and dusk, and so are scarcely seen during the day. They’re most easily found in close proximity to their host plants or as caterpillars.

Brazilian Skipper caterpillars host on two genera of plants, Canna and Thalia. Here in the Lowcountry, we have two native host plants for the Brazilian Skipper, Golden Canna (Canna flaccida) and Powdery Alligator-Flag (Thalia dealbata). Both are rare with few natural populations in South Carolina. However, they are also both popular and hardy aquatic plants commonly sold by plant nurseries, alongside the even more popular and widespread Canna Lily (Canna indica) from South America. All three species are natural host plants for the Brazilian Skipper, which is adept at eating them! The Brazilian Skipper actually goes by another name in the nursery trade. Its infamous alter ego is the “Larger Canna Leafroller” and they can do some damage, albeit superficial damage, to their ornamental host plants, which has evoked the ire of horticulturalists. Brazilian Skipper caterpillars feed using the leaf-rolling technique. Young caterpillars will cut two slits in the edge of a leaf, then fold it over on top of themselves self like a little caterpillar taco, attaching the folded leaf in place with silk. There the caterpillar is safe from the elements and will poke its head out to chew on the edge of its roof. When it eats itself out of house and home, it will move to a new spot on the leaf to tuck itself into a bigger bed and breakfast. These caterpillars are also very unique in appearance. They have a khaki colored head, transparent skin, and green innards spider-webbed with white tracheal tubes, this insect equivalent of lungs being visible through their see-through skin. Eventually this caterpillar will grow to a chunky three inches in length. At that point, it will move to a new leaf and fold it in half. In this final cozy abode it will pupate into a powdery, pale green chrysalis and eventually emerge a fully formed butterfly.

This year for Pollinator Week (6/17 – 6/23) we’re doing a 7-part series about native pollinators on Edisto Island!

Today let’s dive into one special group of pollinators, the Butterflies. Butterflies are a subset of the moths, the superfamily Papilionoidea. Butterflies all share 2 common features: they fly during the day and have “clubbed” antennae. In the Lowcountry, we have about 130 species of butterfly, which come in a wide array of sizes, colors, shapes, behaviors, and life histories.

Butterflies, to be frank, are mediocre pollinators. They have a long, prehensile proboscis to sip nectar out of flowers at a distance. This means they don’t walk around on flowers much and don’t pick up a lot of pollen. Some plants are specialized for butterfly pollination but, generally, butterflies aren’t moving all that much pollen around. Yet, butterflies have 3 special characteristics that make them valuable to pollinator habitat conservation.

First, butterfly caterpillars feed on plant leaves. This makes butterflies a plant “pest” in some ways but, in reality, they and moths serve as a natural check-and-balance for native plants. If one plant has a banner year, moth and butterfly populations spike, eating more of that plant and keeping it in check, so it doesn’t dominate a habitat. In turn, wasps eat these caterpillars so they themselves don’t get out of hand.

Second, butterflies are a great indicator species for the health of a pollinator habitat or ecosystem. Butterflies are also easy to spot and identify, which is important for indicator species. Butterflies respond quickly to environmental changes, weather, and climatic trends. So, their populations follow conditions that ecologists want to keep track of. Being plant eaters, they are also sensitive to insecticide and herbicide use, declining faster than other species and indicating a problem sooner.

Third, butterflies are the quintessential pollinator ambassador for folks. They’re big, they’re pretty, they’re easy to watch, they’re harmless, and can be raised from egg to adult in a classroom terrarium. Their herbivorous caterpillars demonstrate the inextricable link between insects and plants and their adults like the same big pretty flowers we humans love to plant. They’re the poster children of pollinator conservation.

This year for Pollinator Week (6/17 – 6/23) we’re doing a 7-part series about native pollinators on Edisto Island!

The Hutchinson House is an iconic local landmark and touchstone for interpreting African-American history on Edisto Island from the Emancipation through Reconstruction and onward. EIOLT has worked the last 8 years to restore the house and interpret its history.

Just as the House is significant to interpreting our history, the land it sits on is a stellar example for interpreting sea island Pollinator Habitat. EIOLT purchased the adjacent 9-acre lot in 2019 and have diligently maintained its existing wildflower meadows. These fields burst to life in fall with a profusion of native wildflowers that are inundated in a billowing haze of pollinators! We’ve even built a pollinator garden on site to better showcase the beauty of these meadows.

These wildflower meadows are what are commonly referred to as an “Oldfield” habitat. As the name implies, oldfields are agricultural fields left to go fallow. Often, they’re burned or mowed sporadically to control woody plants but otherwise are left to their own devices. An oldfield’s beauty is in its simplicity and purity. A field gone fallow allows for the local “seed bank”, the native plant seeds persisting in the top soil, to be exercised and showcased. Over time, new plant species will germinate from the bank and duke it out in the oldfield free-for-all until an equilibrium is reached. Throughout that process, plant structures, micro-habitats, complex ecological interactions, and diversity will build, creating stellar pollinator habitat.

“Pollinators” are not a monolithic group, it’s a loose collection of animals that spread pollen. Some need pollen, others nectar, some leaves, others leaf litter, hollow stems, bare soil, wet mud, or dead trees; every species has its own unique list of living conditions. Pollinators are a diverse group and, consequently, a diversity of habitat is needed to support them all. Diverse site conditions breed a diverse assemblage of plants, which in turn create a diversity of habitat, a sprawling miniature metropolis of stems and leaves, to support a diversity of pollinators.

Check out this video about the wildflower meadows at the Hutchinson House:

This year for Pollinator Week (6/17 – 6/23) we’re doing a 7-part series about native pollinators on Edisto Island!

Many of our flowering plants rely on pollinators to spread their pollen far and wide. But why do plants need pollinators? Insect pollination encourages cross-pollination between two unrelated plants, increasing a population’s genetic diversity and resiliency to climatic shifts, disease outbreaks, and environmental changes. It also allows a plant avoid producing the massive amounts of pollen needed for wind pollination, making the process more efficient for the plant. This frees up resources the plant can allocate towards growth, or producing nectar.

Nectar is the currency that plants use to pay pollinators for their hard work. It’s a deep-rooted mutualistic relationship. Native plants rely on insects to keep their populations healthy and insects rely on the plants for food. In the end, both groups are better off. This makes pollinators a lynchpin in the long-term health of our native ecosystems, and many plants need cross-pollination to set seed at all. Pollinators are thus extremely important to human agriculture. Many fruit trees and vegetables need insect pollination to produce viable fruit. If insect populations drop, agricultural yields can plummet even though all other site conditions are ideal. This is why recent trends of insect and pollinator declines are disturbing and worrying to ecologists. European Honeybees have been declining due to a myriad of pressures, such as increased misuse of insecticides in residential settings, foreign diseases and parasites becoming more established, and new invasive species, like the bee-eating Yellow-legged and Japanese “Murder” Hornets. These rising threats are highly damaging for beekeepers and agriculture. In parallel, our native pollinators aren’t able to pick up the slack due to similar pressures, such as systemic misuse of insecticides in residential areas, over-reliance on insecticides in agricultural settings, invasive plants, and habitat loss. The Monarch Butterfly and both the Southern Plains and American Bumble Bees are even candidates for listing as endangered species. However, we can mitigate these losses locally if we all help provide our pollinators with pollinator habitat.

This year for Pollinator Week (6/17 – 6/23) we’re doing a 7-part series about native pollinators on Edisto Island!

First things first, what’s a pollinator? It’s simply an animal that moves pollen from one flowering plant to another. Most often this is a flying insect but birds, bats, and ants will also pollinate. We have 5 main groups of insects that serve as pollinators: Bees, Wasps, Flies, Beetles, and Butterflies.

Bees are the powerhouses of the pollinator world. They do the lion’s share of pollination. Adults eat mainly nectar and feed their larvae pollen and nectar. Our native bees, especially Bumble Bees, do the bulk of the pollination in natural areas and small gardens. Honeybees, an exotic domesticated species, pollinate agricultural fields and orchards.

Wasps are anti-heroes among pollinators. Adult wasps eat nectar and do a lot of pollination in the process. They also hunt caterpillars, spiders, and other insects to feed their young. This helps control insect populations and stabilizes an ecosystem.

Flies are the unsung heroes of the pollinators. They do a ton of pollination on smaller flowers that are not often visited by other pollinators. There are also many plants with extremely specialized pollination tailored to just one species of fly. Another group, the Flower Flies, have carnivorous larvae that feed on pests that plague pollinator plants.

Beetles are our pollinator old guard. The original pioneers now stuck in their ways. Beetles are sedentary and uncoordinated, making them inefficient pollinators. However, some plants take advantage of these bumbling beetles to douse them with pollen and to make unwitting pollinators. Butterflies are the celebrities of our pollinators. They’re good looking and they soak up a lot of energy, resources, and attention, but don’t do all that much.

Butterflies are very well adapted to drink nectar and not get pollen on them. Yet, certain plants make use of butterflies as preferred pollinators. Further, butterfly larvae feed on plants, this helps control plant populations and keeps any one plant species from dominating an ecosystem.

This week for Flora and Fauna Friday we’re on the lookout for a rare, coastal plain endemic, backwater wildflower, Powdery Alligator-Flag (Thalia dealbata).

Powdery Alligator-Flag is one of just two species in its genus found in the United States. That genus, Thalia, is our only representative for the Arrowroot family, Marantaceae. Powdery Alligator Flag is a bona fide rare plant here in South Carolina, with only a smattering of population sites in our coastal counties. Edisto Island is notable in being a population stronghold for this rare plant.

Powdery Alligator-Flag can be found in practically all of our natural freshwater backwater wetlands around Edisto Island. It will most readily inhabit shady marshes and shallow swamps around the Island. It is even mildly salt tolerant, and can handle a touch of saltwater intrusion. Powdery Alligator-Flag is an emergent aquatic plant, growing in mucky soil in a foot or so of water along the water’s edge. It spreads laterally through rhizomes into large clumps, or along an entire shoreline in good conditions. Its foliage can reach three to five feet in height with large elliptical leaves a foot long and half as wide. It’s a perennial plant and can even be evergreen through a mild winter. All and all, it looks a lot like a taller, bulkier Canna Lily. However, the most recognizable feature of this plant is not its prominent foliage but its handsome flowers. In about June, Powdery Alligator-Flag gets into full bloom sending up thin flower stalks five to eight feet high. These are capped with a cluster of powdery platinum-white flower buds that eventually bear delicate deep-violet petals. The plant will continue to bloom until fall and the flowers will mature into a spherical nut-like fruit. These nuts are mostly hollow and float, allowing the singular seed within to journey across the water. Despite its rarity and specialized life history, Powdery Alligator-Flag is actually a very hardy plant and a perfect native addition to any wetland garden, pond edge, or detention basin. Powdery Alligator-Flag tolerates full sun, partial shade, mucky soils, fluctuating water levels, freezing, and even a dash of salt. In return it provides towering foliage, beautiful flowers, and wildlife habitat. Thanks to these traits, it’s grown and sold widely in aquatic plant nurseries. Powdery Alligator-Flag is also a host plant for the Brazilian Skipper butterfly (Calpodes ethlius), a large golden-brown skipper common in subtropical regions where Canna and Thalia plants are abundant. These butterflies are scarce in South Carolina but locally abundant where Powdery Alligator-Flag is established.

This week for Flora and Fauna Friday it’s a long-necked, fowl-flavored, slow-moving slough citizen of the Southeast, the Chicken Turtle (Deirochelys reticularia).

The Chicken Turtle is found throughout the coastal plain of South Carolina. It is scarcely seen in many locales but is particularly common here on Edisto Island. Chicken Turtles inhabit freshwater marshes, bottomland forests, backwaters, and other shallow, vegetated freshwater wetlands. Chicken Turtles share many physical characteristics with other turtle species in the family Emydidae, but have a few standout features of their own. In general appearance, their shell is a bit taller and smoother than other pond turtles. Their carapace has a faint yellow, net-like pattern across its top and their plastron is a solid golden-yellow below. A Chicken Turtle’s front legs have a thick yellow stripe running from toes to shoulder and the side of its head has thin, parallel yellow lines. However, the most standout feature of the Chicken Turtle is its head and neck. The head of a Chicken Turtle is noticeably longer than other pond turtles and its neck is proportionately almost twice as long as its cousins! Chicken Turtles use their long neck to hunt crayfish, small fish, insects, and amphibians. It allows them to reach out and suck up or snap down on prey at a distance in the shallow waters they inhabit, where moving quickly isn’t an option.

Chicken Turtles have some other interesting quirks as well. Unlike most turtles, they nest in fall and winter, rather than spring. Their eggs in tandem have a prolonged incubation time in response to colder temperatures, preventing hatching until spring. Further, rather than moving to a new home when their shallow wetlands dry out in summer, they instead head to the uplands to aestivate underground until the wetland floods again. Aestivation is similar to hibernation but is done in summer, usually by reptiles or amphibians and when the weather is too hot or too dry. Chicken Turtles also grow rather fast for a turtle but have a surprisingly short lifespan of only about 20 years.

Lastly, the name “Chicken Turtle” is a reference to the historical account that these turtles taste like chicken! It also is a fitting description of this turtle’s long chicken-like neck. Chicken Turtles were once a mainstay in the southern delicacy of turtle soup, as they apparently taste much better than our other turtles. Nowadays, turtle soup is no longer on the menu in Charleston. But it’s still a delicacy on the other side of the Earth. Until recently, there were practically no limitations on the collection of wild turtles in South Carolina. This resulted in South Carolina becoming a hotbed for poaching and the black market sale of our native turtles overseas to Asian meat markets. Our turtle populations crashed as a consequence and new laws were passed in 2020 to staunch the decline and crack down on poaching.