This week for Flora and Fauna Friday it’s a tough, lush, turf-grass that’s a possibly native to the Sea Islands, St. Augustine Grass (Stenotaphrum secundatum).

St. Augustine Grass, also called Charleston Grass, is a perennial, occasionally even evergreen, turf-grass. It is tolerant of heavy shade, wet soils, poor soil fertility, drought, and even saltwater intrusion, but does not tolerate full sun nor frost well. It grows as a groundcover with heavy stoloniferous stems that run along the surface of the soil, dropping roots as they go. Its leaves are a lush, deep verdant green, are soft and drooping, and can exceed a foot in length in ideal conditions, if left untouched. Its flowers are a flattened, thickened spike that rises straight up above the ground. It will bloom throughout summer. St. Augustine Grass is a host plant for many of our native butterflies’ grass-eating caterpillars, such as the Carolina Satyr, Southern Skipperling, Whirlabout, and Clouded Skipper.

St. Augustine Grass is found widely throughout the Sea Islands of South Carolina and Georgia and is planted extensively for lawns throughout the Lowcountry of South Carolina, as well as Florida, the Gulf Coast, and other subtropical climates worldwide. The natural range of St. Augustine Grass is something botanists are still debating and contesting. Many sources claim it is native to the coastline of the Southeast, others the Gulf Coast, and others say it is native to South Africa. A clear answer isn’t yet known. What I can tell you for sure is that the first place it was described by science was in 1788 by the botanist Thomas Walter from Charleston, South Carolina. More modern research appears to indicate that this grass is an extensive species-complex spanning from Charleston through the Gulf Coast and Caribbean down to South America and across the Atlantic Ocean to West and South Africa, with various lineages that have spread both naturally and by humans, including into the Pacific. All other species of the same genus, Stenotaphrum, are found in the Pacific Ocean. As it stands, the origin point of St. Augustine Grass as a species is still unknown. In my personal opinion, it likely originated in Africa and was spread to North America either naturally by ocean currents thousands of years ago or by Europeans during colonization sometime during the last five centuries.

Let’s finally address the elephant in the room. (Hello there Mr. Elephant!) Today I’ve spotlighted THE turf-grass of the Sea Islands, Charleston Grass itself. Turf-grass lawns and monocultural turf-grass lawn management have been catastrophic for native plant and insect biodiversity across the entire United States since the 1940s. A traditionally managed turf-grass monoculture contains no native plants and can sustain next to no native insects, let alone wildlife. I do not, and will never, advocate for creating nor maintaining a turf-grass monoculture around your home, business, et cetera. But if I can’t convince you not keep a turf-grass lawn, then at least pick the lesser of the evils. In my opinion, the old wild-type variety of St. Augustine Grass is the closest thing to a native turf-grass we have in the Lowcountry. I’ve inherited some amount of St. Augustine Grass in every lawn or park I’ve ever managed and I can tell you from firsthand experience that, when managed tactfully, it will support some native wildlife and won’t exclude all other native plants. It is by no means a team player and will crowd out many smaller plant species. Yet if left shaggy, and the “weeds” left alone, St. Augustine Grass can provide wildlife value and management utility in our coastal landscape, without exacerbating the harm already done, and can be readily converted to a more natural botanical community later on. However, a native grassland or meadow will always be the best replacement for any lawn.

This week for Flora and Fauna Friday it’s our darling bird on Deveaux Bank, the Whimbrel (Numenius phaeopus).

Whimbrels are a cosmopolitan species, meaning they can be found all across the globe. Yet, they have four subspecies, three that breed in Europe and Russia and then our Hudsonian Whimbrel (N. phaeopus hudsonicus) who breeds in North America. Within the Hudsonian Whimbrel, there are two disjunct populations, one on the west coast of the Pacific Ocean and one on the east coast of the Atlantic Ocean. Here on Edisto Island, we see the Atlantic population of the Hudsonian Whimbrel.

The Whimbrel is a large shorebird, at about a foot high on stout black legs. Their plumage is a camouflaged pattern of mocha-brown and bone-white, each color breaking up the other in dots and dashes into a seamless cryptic checkerboard across their whole body. Their most standout feature is their long black bill that curves down towards the tip and, at the opposite end, blends back onto the head into a set of dark racing-stripes across their dome and a heavy line through their eye. Apart from their larger and scarcer cousin the Long-billed Curlew (N. americanus), there’s nothing else in South Carolina like a Whimbrel! Whimbrels spend their days in our saltmarshes and tidal creeks resting and foraging. Their diet consists largely of fiddler crabs, which they snatch from the surface of the marsh or pluck from deep within their intertidal burrows. Apart from fiddlers, they also eat a good deal of other crustaceans as well as some small mollusks and fish when available. When tides are high, Whimbrels retreat to oyster banks, hammock islands, and sometimes even docks, to rest and digest until the tide ebbs. Whimbrels use their time here on Edisto Island to put on the pounds they need to fly up to the Arctic Circle to nest in the Canadian tundra. Some Whimbrels overwinter here in the marshes of the Edisto Rivers and the ACE Basin. Some younger birds may even spend their first summer on the South Carolina coast, forgoing migration. However, the prime time to find a Whimbrel on Edisto Island is during their spring migration.

Edisto Island is of the utmost importance to the survival of the Atlantic Hudsonian Whimbrel population. During spring migration, nearly fifty-percent of our total Atlantic population will simultaneously use Deveaux Bank as an overnight roost, flying in by the thousands as the sun sets. Deveaux is an undeveloped sand bank at the mouth of the North Edisto River, in between Seabrook and Edisto Islands, which is owned and managed by SCDNR. In 2019 the importance of Deveaux Bank was made known globally to ornithologists and shorebird conservationists through research by SCNDR biologists. From the research, scientists had learned where the Whimbrels were roosting, at an astonishingly high concentration, but not where they were all dispersing to forage during the day. In 2024, new research to answer those questions is ongoing and its preliminary results have revealed the importance of Edisto Island and the ACE Basin to the survival of the Atlantic population of the Hudsonian Whimbrel. Our migrating Whimbrels all roost on Deveaux at night but, in the day, they disperse across the tidal marshes of Edisto Island, Toogoodoo Creek, Bohicket Creek, St. Helena Sound, the Kiawah River, and even all the way over to Beaufort to feed. They are dependent on the entirety of the tidal ACE Basin and its surrounding sea islands’ marshes to survive, with Edisto Island housing the closest all-you-can-eat fiddler crab buffet to Deveaux Bank. Whimbrels use their time here on Edisto Island to put on the pounds they need to fly up to the Canadian tundra in the Arctic Circle to nest.

Without SCDNR’s management of bird sanctuaries like Deveaux Bank and the prior decades’ worth of tireless land protection work by the Edisto Island Open Land Trust and our peers in the ACE Basin Task Force, we could have already lost the Whimbrel on the East Coast by this point. Whimbrels are in steep decline and Deveaux Bank and the ACE Basin represent what may become their last stronghold on the East Coast. With each passing year, South Carolina’s preeminence, cooperation, and forward thinking actions in the arena of landscape-scale conservation are being realized, recognized, and solidified as the standard by which all other regions of the country must compare, the ACE Basin being a crown jewel of those efforts. EIOLT is a proud member of this cooperative conservation community and thanks you, dear reader, for your support that makes it possible for EIOLT to continue our efforts to protect land containing critical habitat for imperiled coastal species, like the Whimbrel, who depend on Edisto Island to survive.

This week for Flora and Fauna Friday, it’s a departure from the norm to talk more generally about an ecological concept, and to highlight some foreign flora and fauna. Today you’re getting a crash course on the major Invasive Species of the South Carolina Lowcountry.

I’ve been writing this series for nearly seven years now and, if you’re a loyal reader, you may have noticed that I tend to look at practically all aspects of our Lowcountry ecosystems with an air of positivity and reverence, bordering occasionally on unfeigned evangelism. I tend to take the side of the scorned and maligned members of our natural world. The vipers, sandburs, spiders, coyotes, thistles, and even the rats; I’ve praised them all and preached of their importance.

Today’s subject is different. There are a select few species that have wrought my utter contempt. Beings so wretched and vile they deserve no safe harbor in this landscape. Invaders from exotic lands who undermine the foundation, tarnish the beauty, and corrupt the sanctity of this Sea Island we’ve toiled so hard to conserve. I’m speaking of invasive species, both plant and animal. Insidious and existential threats to the ecological integrity of Edisto Island and the whole of the Lowcountry.

First, let’s define what an invasive species is. An invasive species is an introduced exotic organism that has a measurable, harmful, damaging impact on native species and, by extension, the natural ecosystem which it invades. To expound upon this we have to also detail what an invasive species is not. Firstly, a native species cannot be invasive within its natural range. This generally extends to “Range Changers” which are native species that expand their range into a new area due to favorable changes in the landscape, for example Coyotes and Cattle Egrets. An “exotic” species is simply an organism native to someplace else, which now exists in a place where it never naturally occurred. Further, not all exotic species are harmful or damaging. An exotic species that establishes in a new area but doesn’t cause any meaningful harm is referred to as a “naturalized” species. So it’s only when things end up where they’re not supposed to be AND when everything else starts to go wrong as a consequence that an “invasive species” manifests.

But, before we continue, it’s important to note that an invasive species is not invasive in its own native range. It has a home where it belongs and where it plays an important role in its natural ecosystem. There, they also have predators and pests that keep them in check and competing species to level the playing field. It’s only when they’re introduced as an exotic in a foreign land that they become freed from these natural biological controls and can usher in an ecological plague.

Out of all the invasive species that occur in the South Carolina Lowcountry, of which there are well over a hundred, there are three plants and two animals that come to my mind as the worst of the worst. These five have precipitated unfathomable ecological destruction and economic burdens throughout the Southeast: Chinese Privet (Ligustrum sinense), Feral Hogs (Sus scrofa), Chinese Tallow Tree (Triadica sebifera), the Red Imported Fire Ant (Solenopsis invicta), and Common Reed (Phragmites australis).

Chinese Privet (Ligustrum sinense) is the poster child for invasive plants, a wanted poster that is. Chinese Privet was introduced to the United States in the mid-1800s. It has opposite, evergreen leaves and showy clusters of white, spring-blooming, fragrant flowers. As such, it was planted widely as an ornamental shrub. However, following the Civil War, many agricultural fields were laid fallow and Chinese Privet began leaching out into the Southern landscape. Its dark blue-purple drupes in summer are attractive to birds, who gorge themselves before flying off, spreading the seeds as they go. Chinese Privet can grow on a wide array of soils, tolerates full sun and partial-shade, spreads clonally, and is evergreen with a dense canopy. These characteristics create the crux of what makes it so terrible. Once established on a field row or roadside, it begins a generational march into the forest understory, creating an impenetrable privet thicket that slowly snuffs out all plant life below it. When a tree falls and light hits the forest floor, it creates a pocket of prime songbird habitat, which Privet then exploits. The birds unknowingly hop-scotch the Privet into these clearings, allowing it to advance its front with ease. Soon the Privet saturates the forest floor and withers away the surrounding biodiversity. Privet is an over-bearing threat in the upstate of South Carolina. Here on Edisto Island, we have a fair bit of privet but, thankfully, it is mainly kept in check by our native Sea Island flora. Our native trees and shrubs often grow fast enough and thick enough to freeze Privet in its tracks before it can spread. Yet, it often still secures a foothold in fallow fields and around human developments. A quick tangent, many of our invasive plants here in South Carolina originate from China or Japan. This is not a coincidence. Certain regions of Japan and especially coastal China have a very similar climate and soils to the Southeast. So, when brought here, their plants grow equally as well, but without the other species that naturally control them.

Feral Hogs (Sus scrofa) are a special kind of blight. They look like a typical pig, albeit more athletic and hairier, because that’s all they are. Feral Hogs are descendants of domesticated pigs, gone feral. Their ancestors escaped from captivity centuries ago and returned to life in the forest. Just the wrong forests on the wrong side of the ocean. Although they’re fully feral, they’ve retained all those traits that make pigs a versatile and adaptable livestock. Feral Hogs can reproduce at an astonishing rate, with sows able to breed at less than a year old and capable of raising 15 or more piglets a year. Under ideal conditions, a Feral Hog population can more than quadruple in a year. Hogs are unbelievably intelligent, being smarter than most dog breeds, and they learn how to evade people, defeat barriers, and avoid traps rapidly. They’re also big, tough, and fast. Weighing over 100 pounds, not much can threaten a full grown sow. Full grown, a boar can exceed 200 pounds and wields a face full of pointed tusks. Hogs, especially boars, can be aggressive and a deadly threat to people and pets. A Hog’s nose is incredibly sensitive to both smell and touch, letting it find food buried underground. Yet it is also strong enough to function like a plow and is capable of upturning the most hard-packed soils and digging under fences. Hogs will eat anything and everything, and I mean that. They are true omnivores and will eat plants, tubers, seeds, nuts, insects, reptiles, fresh carrion, bird and sea turtle eggs, and any mammal or bird they can catch. All these factors combine to make Feral Hogs, by no exaggeration, an existential threat to the conservation of many rare and endangered species in the South. Feral Hogs can single-handedly decimate native plant and wildlife population, and may even extirpate them from the landscape. They destroy farmer’s crops at every chance they get and pollute waterways by upturning, wallowing, and defecating in creeks and wetlands. Their constant digging and eating of native plants plows and primes the soil for invasive plant species to set seed and take root, further destroying an ecosystem. Wherever they go, Feral Hogs wreak havoc and bring destruction. The only silver lining to this blight is that they are at least made of bacon! There are ostensibly no harvest limits or hunting restrictions on Feral Hogs in South Carolina. This is to encourage continuous and relentless population control. However, a sickening trend has developed nationwide, some people have deliberately spread Feral Hogs to new counties and states in order to create sport hunting opportunities. This is a highly illegal and a morally bankrupt practice, but still it continues to spread Feral Hogs within the United States. We are extraordinarily blessed on Edisto Island to not have any established populations of Feral Hogs. However, Hogs do occasionally swim across the South Edisto River. Thankfully, so far, they have been kept off our Island by our responsible local landowners.

Chinese Tallow Tree (Triadica sebifera), or perhaps more widely known as Popcorn Tree, is in my opinion the most destructive invasive plant established on Edisto Island. It has alternate, diamond-shaped leaves, white seedy fruits, and a pale-gray lightly flakey bark. Chinese Tallow was first introduced to the United States in the late 1700s for soap making but later became a popular ornamental tree due to its colorful fall foliage and large white seeds. It is well adapted to growing in coastal wetlands and tolerates shade, full sun, well drained soils, saturated soils, and even occasional saltwater flooding. Once established, Chinese Tallow grows unimpeded, as its foliage is toxic to herbivores. It grows quickly into a small tree and can begin to produce seeds when it is only a few years old. Its seeds are coated in a thick wax, which gives them their characteristic white color and the “popcorn” common name. This wax is an attractive food to many birds, including bluebirds, woodpeckers, and cardinals. They swallow the seeds whole, digest the wax, and pass the seed some time later somewhere else. This disperses Chinese Tallow seeds far and wide. At the same time, seeds that aren’t eaten fall to the ground in winter. Our Lowcountry wetlands are often flooded in winter and these seeds float, allowing them to disperse by wind and floodwater to distant shores. Some seeds inevitably germinate below the parent tree as well. These two dispersal mechanisms result in Chinese Tallow taking root in every inaccessible corner of an intact wetland in as little as five years. That’s when the real problems start. Chinese Tallow is an ecosystem engineer, one that engineers the subversion and destruction of healthy wetland ecosystems. Once established in a wetland, its seeds can lay dormant in the soil. All it takes is one disturbance event, like a flood, a drought, a fire, or salt intrusion, to activate these seeds like sleeper agents, which quickly grow into full blown trees. Each one of these trees acts like a water pump that sucks water from the wetland soils and evaporates it into the atmosphere. This upsets the balance of the wetland, which allows for more Chinese Tallow seeds to germinate. This creates a positive feedback loop where Chinese Tallow starves the native wetland plants for water and then takes their place the following year. This eventually creates a nearly pure stand of nothing but Chinese Tallow, which then wrests control over the wetland’s hydrology. Eventually, if the soil dries out enough, upland plants may try to intrude. The upland plants shade out the tallow and the Tallow stops pumping water, which causes the wetland to flood, which kills the intruding upland plants, which allows the Tallow to repopulate. It is truly a diabolical strategy, a vicious cycle by design.

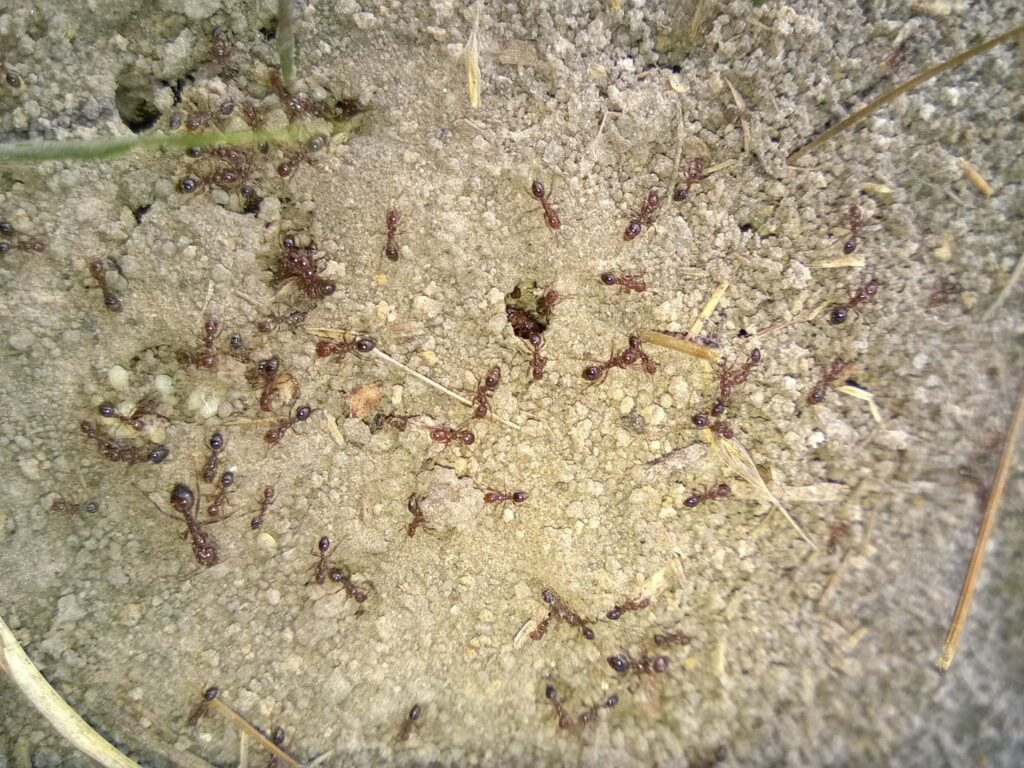

Red Imported Fire Ants (Solenopsis invicta) are small ants with a dark-red head and thorax and a darker-red or black abdomen. They build large, porous mounds with a sponge-like appearance and no central entrance. Fire Ants are likely the single most destructive invasive animal to southeastern wildlife biodiversity, even more so than Feral Hogs. The difference between these two invasive animals is that Hog damage is often isolated and is impossible for any land manager to miss. Fire Ant damage is omnipresent and insidiously hidden. Red Imported Fire Ants were unintentionally introduced into the United States in about 1920. These ants have then spread like a fire across the United States since and can be found in every corner of South Carolina. The full extent of the ecological damage that has been caused by Fire Ants is almost impossible to quantify or gauge. Fire Ants eat practically any animal they can reach and they can live in practically all habitats from fields to savannas, from forests to beaches, from parking lots to even rice field marshes. Over the last century they have systematically invaded every corner of South Carolina and secretly waged an unyielding war of attrition on all fronts against our native wildlife. They’ve imperiled turtles, butterflies, quail, salamanders, bumblebees, snakes, bats, and even our native ants, nothing is safe from the onslaught of Fire Ants. What makes Fire Ants so particularly destructive is multi-fold. To start out with, unlike all our native ant species, they’re violently aggressive, attacking anything they encounter whether it be a threat, potential food, or a human foot just minding its own business. Our native wildlife have no adaptations to deal with these unprovoked swarm attacks. But fleeing does little good as Fire Ants are everywhere. Fire Ants have spread so far and wide because they’re adaptable, but also because of their teamwork. Normally, ant colonies fight with other neighboring ant colonies, even within their own species, over resources and territory. However, Red Imported Fire Ants colonized the United States through just a few isolated introductions. This has resulted in all the Fire Ants being one giant extended family, meaning they see each other not as enemies but as allies. The consequence is that all the Red Imported Fire Ants in the United States operate as one gargantuan, unstoppable supercolony which persists at unnaturally high colony densities and, like an out of control fire, slowly and surely consumes everything it envelopes. This unceasing horde of ants has decimated the populations of many ground nesting birds, turtles, endemic amphibians, pollinators, and native insects. Much of this destruction occurred rapidly and out of sight, before ecologists even knew it had begun. When wildlife populations plummet, it has ripple effects throughout an ecosystem. If there is a population decline in pollinators, herbivores, and/or seed dispersers, their decline can cause native plants to either suffer or grow out of control, creating a positive feedback loop known as a trophic cascade. These ecoregion-wide ecosystem changes caused by Red Imported Fire Ants have been ongoing for over a century now in some places, their scale and severity are so acute yet diffuse as to be nigh incalculable by ecologists.

Common Reed (Phragmites australis), better referred to as Phragmites, represents a threat like none other to the tidal marshes of the east coast. It is a tall wetland grass with bluish-green leaves, a thick cane-like stem, and a large plume-like seed head. Phragmites was introduced from Europe in the 1800s, assumedly by accident. Phragmites thrives in the brackish tidal wetlands of South Carolina where it can grow over fifteen-feet tall and spreads by rhizomes underground to form vast monocultures in our tidal wetlands. A monoculture is when only one species of plant grows in a specific area. This can be normal and healthy, as in the case of our Smooth Cordgrass saltmarsh, but more often than not it is the destructive consequence of an invasive species invading a natural habitat and being left unchecked. The latter is the case with Phragmites. Phragmites has characteristics unlike any of our native wetland grasses which give it an unnatural advantage in our coastal wetlands. Phragmites grows almost twice as tall as any of our native marsh grasses, allowing it to shade out its competition. It forms dense, evergreen thickets that, in addition to the shade, further prevent native plants from competing by raising the elevation of the marsh substrate. It can also tolerate fairly high salinity levels and dramatic tidal fluctuations, allowing it to establish on the margins of saltmarsh or within the brackish zones where native wetland plant populations are naturally unstable. These traits together give Phragmites the ability to elbow its way into even the healthiest of marsh ecosystems, where it runs amuck unfettered, smothering native marshes as it goes. These Phragmites marshes have a much lower species biodiversity and don’t support all the same endemic species that our native marshes nurture. Many of these species being already critically imperiled from habitat loss, over harvest, water quality degradation, and sea level rise. Phragmites also threatens managed tidal impoundments and historic rice fields, which many species of waterfowl and shorebirds depend upon within the Atlantic Flyway. On Edisto Island, the spread of Phragmites is sporadic and so far has been limited to impoundments and brackish systems along the Intracoastal Waterway, where ships and dredging machinery from out-of-state have shed hitchhiking seeds to be swept inland by the tides. Phragmites is not able to survive the full brunt of saltwater like Smooth Crodgrass can, but it certainly is trying to gain a foothold around Little Edisto and deeper into the heart of the ACE Basin. [Phragmites is not to be confused with Giant Cane (Arundo donax). Giant Cane is a very similar looking ornamental exotic that usually exceeds ten-feet in height and grows on moist uplands, rather than marshes. It can also be invasive, just not to the same degree nor in the same habitats.]

The truly insidious thing with these five invasive species is that there is currently nothing that we can do to thoroughly control them. They are all still ever spreading on the American landscape. All have been running rampant, mostly unchecked, for nearly a century or more but some have only truly unleashed havoc in the last 50 years. Once any one of them becomes truly entrenched, they’re practically impossible to stamp out. The only solutions to controlling them so far require expensive, continuous, active management just to keep their populations under control. If these efforts cease, the destruction would be unfathomable. This makes the idealistic concept of preserving ecosystems in their natural state (E.G. taking a hands off approach and letting nature take its course) now untenable in the Southeast. Right now, the damage done by the hands of man can only be staunched with the deliberate and desperate actions of those same hands. Taking a hands off approach with our natural landscapes today is tantamount to throwing what’s left over to the Hogs.

That’s also just the big 5. There are over a hundred more invasive species in South Carolina and more keep appearing with each passing year. Some have even made their debut in the State in our own backyard, for example the Asian Long-horned Beetle (Anoplophora glabripennis) outbreak in Hollywood, SC and the Cuban Bulrush (Oxycaryum cubense) invasion in Green Pond, SC.

However, all hope is not lost! The more people who recognize and rectify these existential environmental threats, the sooner we can snuff them out. Biologists are feverishly working on developing biological controls to wrangle these five pests into submission and one day these efforts will come to fruition. In the meantime, ecologists and land managers toil day in and day out to expunge invasive species from our natural landscapes. You too can play a vital role, especially when it comes to controlling invasive plants. Take a gander around your garden, your yard, your driveway, or your property. You might be surprised to find where invasive plants have already taken root. If they have, cut them down and dig them up. Then keep an eye out for when, not if, they return. If you don’t have land yourself, considering volunteer with SCDNR, USDA, EIOLT, or other local nonprofits on invasive species work days. On the other side of the coin, when you’re perusing plants at your favorite big box store or nursery, double check that that shrub you’re eyeing isn’t a Trojan horse. If we all do our part, if we plant native plants and root out invasive species, we can conserve and improve what we’ve still got left of the Lowcountry’s natural history.

This week for Flora and Fauna Friday it’s the balaclava’d bard of the bottomland, the Hooded Warbler (Setophaga citrina).

Amidst the droning drill of cicadas and bloodthirsty buzzing of mosquitos, a high and piercing warble hacks through the stagnant atmosphere of the floodplain forest. A Hooded Warbler sings his heart out as he darts and dashes from ash to elm, down grape to cane, taking but a moment at you to crane, a curious intruder in his floodplain domain. It’s always a wondrous sight in the Lowcountry spring when a male Hooded Warbler graces you with his presence. He’s a songbird who masks his face in a hood of black and drapes his back in olive, as if an extension of the green-washed shadows below the forest where he lurks. Yet, in stark contrast, down his belly and through opening in his hood beams the radiant glow of golden yellow, like a sunbeam crashing onto the forest floor. It’s an experience that arrests thought and directs attention squarely to it.

Hooded Warblers are found widely within the Southeast and all across South Carolina from spring to fall. They inhabit mature hardwood forests and river valleys. Here in the Lowcountry and Sea Islands, they are particularly fond of river floodplains and swamp margins where they forage within the dense and shaded tangle of understory plants. Hooded Warblers subsist on a diet of insects, spiders, and other arthropods, which they glean from leaves and snatch from the air. Males and females are similar in appearance, being olive-green above and sunflower-yellow below. However, males don a signature black hood across their cap and beard, making him an unmistakable sight. Both sexes also have a black bill, pink legs, and white on their outer three tail feathers. Hooded Warblers spend their winters in the tropics of Central America and the Caribbean before returning to South Carolina in spring to nest. In the Lowcountry, males start staking out their nesting territories in early April. They do so through the power of music. Birdsong, especially with Warblers, is employed as both a fence and a billboard. Each male sings to advertise where he, himself, is to the ladies and to his rivals. He also listens to where his rivals are. If it sounds like the neighbors are encroaching on his turf, he’ll head that way to give them an earful. Although more creative mnemonics exist, in my opinion the male’s song is most accurately described as “weeta-weeta-weet-Tee-o.” It’s a clear song which alternates up and down, before rising sharply in volume and pitch for its penultimate note, then trailing away at the end.

This week for Flora and Fauna Friday, we’re on the lookout for our local Clover, Carolina Clover (Trifolium carolinianum).

Carolina Clover is native to the southeastern United States and found around the coastal plain of South Carolina. In the Palmetto State, one can find over a dozen species of Clover, but only two of those are native. Of those two native species, only Carolina Clover is found on Edisto Island. Unlike its showy exotic cousins, such as Crimson Clover (T. incarnatum) and Arrowleaf Clover (T. vesiculosum), Carolina Clover flies completely under the radar, out of sight and out of mind. It’s a hard plant to spot, even when you know what to look for. Rather than bearing proudly colorful flower spikes and lushly dense, verdant green leaves, Carolina Clover hides amongst its surroundings. Its leaves are trifoliate, with three leaflets, like all our other Clovers, but its leaves are small, muted in color, and sparsely found between its weedy neighbors. Its flowers are tiny and delicate with pink-washed and white petals held limply in a drooping ball of rosy-red flower stalks, down-facing and hidden from sight. Their flowers peak in mid-spring, from April into May, and are visited by myriad native pollinators.

Carolina Clover is one of many of our native legumes that are supremely adapted to sand barrens. It can tolerate acidic and nutrient poor soils, drought, and fire. It also has many wildlife benefits, being a desirable browse to deer and rabbits, a pollinator plant sought after by bumblebees, and a host plant for several of our smaller butterfly species. Clovers, even some of the exotic ones like White Clover (T. repens), also have great value in replacing turf-grass in alternative lawns. As they are legumes, Clovers can fix nitrogen from the air. When they shed old leaves or are mowed, the nitrogen in their leaves is drawn into the earth where it supports healthy soil and the growth of its neighboring plants. So, unlike turf-grasses, Clovers and other native legumes can build soil without fertilizer, all while supporting native wildlife and pollinators. So consider letting Carolina Clover, and our other native legumes, have a home around your home!

This week for Flora and Fauna Friday it’s the homecoming for an odd and ephemeral butterfly, the Yucca Giant-Skipper (Megathymus yuccae).

The Yucca Giant-Skipper is found from California to North Carolina, with a scattered distribution here in South Carolina, and is a fairly rare butterfly across its range. They tend to inhabit dry, open, sandy habitats, and only those where Yuccas thrive. These include the Longleaf Pine savannas of the Sandhills, the maritime fringes of the Sea Islands, and the beach dunes of our barrier islands.

The Giant-Skippers are South Carolina’s largest members of the Skipper butterflies, family Hesperidae. Like most Skippers, they have compact triangular wings and a torpedo-shaped body. Unlike most Skippers, they’re giant! In appearance, our Yucca Giant-Skipper is a rich ebony-brown across the body and wings. Those wings are accented by spots of silver and golden-tan, with tan fringes above and silver frosting below that bleeds down onto the flanks of the body. In profile, they look like no other butterfly. I liken them to a thumb with wings.

The Yucca Giant-Skipper is big for a Skipper and dense for a butterfly. By weight, they’re likely our heaviest butterfly species, despite having half the wingspan of our larger Swallowtails. This barrel-chested bug needs that mass for two things: power and fuel. The Yucca Giant-Skipper is the drag racer of the butterfly world. They’re fast, very fast; all gas, no brakes. From firsthand experience, I can tell you they effortlessly cruise at about 30mph as their baseline speed. There are even anecdotal accounts of Giant-Skippers breaking 60mph! Their speed is thanks to their body size, which allows them to cram in the muscle mass to fly faster than many songbirds. To maintain that speed, they have to burn the body fat they carry around as fuel, but there’s no topping off their tank. Yucca Giant-Skippers, as adult butterflies, don’t drink nectar from flowers. They don’t eat anything at all. Once one emerges from its chrysalis, its only goal is to reproduce and start the next generation. Yucca Giant-Skippers only fly in one brood each year, which emerges in mid-April. Adults are often only active in the morning, resting all afternoon while hidden in the vegetation. Their scarcity, brief flight-time, and speed all make them a very hard butterfly to lay eyes on.

Female Yucca Giant-Skippers lay eggs on, predictably, the leaves of Yucca plants. Eggs are an eighth-of-an-inch wide and pale-green fading to khaki, with a small dark dot at the top. Once hatched, the young caterpillar crawls to the tip on top of a Yucca blade, where it weaves a parasol of silk between the leaf edges and hides within. There it feeds on the leaf tissue, turning the blade tip brown. Once it reaches about an inch in length, the walnut-brown worm wriggles its way to the bud of the Yucca, where it begins to bore a hole straight down into the stem and root of the plant. Here the caterpillar will feed on the starchy wood of the Yucca to pack on the pounds. The caterpillar maintains a hole back at the top of the stem. Around this exit it slowly builds a tubular “tent” out of waste and silk, inside of which it will eventually undergo metamorphosis and emerge a chubby cherubic speed-demon the following spring.

The Yucca Giant Skipper was historically relatively abundant around Charleston, but they practically vanished some decades ago. Then, out of the blue in 2022, they returned home! It’s assumed there was a recent bumper crop of Yucca Giant-Skippers somewhere inland, and those over-crowded butterflies headed straight to the beach for their first and only spring break. Since then, their populations have been strong on the Sea Islands, to include Edisto Beach. It’s almost like they never even left.

This week for Flora and Fauna Friday we have an uncommon member of the maritime forest understory, Wild Olive, or Devilwood (Catrema americana).

Wild Olive is found throughout the coastal plain of the Southeast and all of the South Carolina Lowcountry. It is not a rare plant but scarcely seen in the modern landscape. It can grow on a wild range of soil conditions but seems to do best on the fertile, sandy soils of the Sea Islands and the coastal plain sand ridges. It is especially well adapted to the true maritime forests of our barrier islands. Devilwood is thoroughly an understory plant, thriving in the dappled light filtering through a forest canopy. It grows as a tall shrub, usually ten to twenty feet high, with multiple stems and twisted trunks. Devilwood purportedly gets its common name from its dense wood, slow-grown and twisted, as anyone who attempts to carve it, or even just split it for firewood, is in for a devil of a time! Wild Olive is evergreen and, like other understory evergreens, has dark, inky-green leaves that are simple, elliptical in shape, waxy, and leathery. As a member of the Olive family, Oleaceae, its leaves are oppositely arranged and, like most Olives, it blooms with clusters of small, fragrant, cream-white flowers. These spring flowers are highly attractive to many of our native pollinators. Pollinated flowers mature into dark-blue drupes. These fruits are eaten by birds and the Wild Olive seeds spread in the process.

Devilwood is an excellent addition to most any coastal garden or yard. Its aforementioned flowers and fruits are attractive to pollinators and birds, and its dense evergreen foliage provides protective cover for many songbirds year-round. It accepts a variety of southeastern soils, is practically disease free, drought tolerant, and can tolerate full sun or shade, making it an incredibly flexible option in landscaping. It even takes well to pruning and hedging.

This week for Flora and Fauna Friday it’s the colorful, colonial, and cacophonous Red-headed Woodpecker (Melanerpes erythrocephalus).

With a bellowing and a banging this boisterous bird comes barreling up the bottomland to lit above a beaver dam. Black and white and red all over the dome, this bird is unmistakable by eye. A sold blood-red head, silver bill, a jet-black back and tail, along with snow-white belly and secondaries gives this bird an utterly one-of-a-kind plumage in the Eastern United States. And it’s also unignorable by ear, with startled vibrating screams and resonant barking rattles that ring throughout the canopy as one, then two, then four birds join in. Red-headed Woodpeckers are, sort of, a colony forming Woodpecker. They’re not a close nit family unit, and thus not a true colony, but more a tenuous alliance of neighbors to further self-interested goals, like an HOA, or maybe a street gang, or both. The Red-headed Woodpecker is found year-round throughout much of the South, to include all of South Carolina. They are omnivorous and their varied diet consists of wood boring insects, flying insects, seeds, nuts, fruits, and small vertebrates. They also build seed caches to help get them through the winter. Red-headed Woodpeckers inhabit forests dense with hardwood trees and have a strong preference for floodplains and the margins of large wetland systems. In the Lowcountry, Red-headed Woodpecker colonies can most often be found along river floodplains, bottomland margins, sea island lowlands, ghost forests, and beaver dams. These forest types foster environmental conditions that stress the trees and occasionally kill off a good number of them. These environmental stressors and periodic tree die offs create the perfect little suburban neighborhood for a merry band of miscreant Red-headed Woodpeckers to move into. The stressed trees of these environments are prone to disease, which subsequently invites insect pests, creating a pantry for our Woodpeckers to pursue. The already dead trees harbor insects as well but, more importantly, they collectively create a ghost forest. Here the Woodpeckers can excavate their nest cavities for years going forward. Surrounding these dead and dying trees are generally also some oaks, beeches, and other seed-bearing trees that are doing just fine on the rich wetland soils and produce a bounty of seeds for the Woodpeckers to feast upon each year. Not a bad neighborhood for a Woodpecker to move into! But Red-headed Woodpeckers don’t want neighbors. They have a darker side and they are known to raid other birds’ nests to eat the eggs and chicks, or to injure the parent birds in the process. This harassment continues until the encroaching birds leave or die. This exclusionary behavior and their particular habitat preferences give Red-headed Woodpeckers a sporadic distribution across their range. They concentrate into very specific regions of the landscape and are scarcely found anywhere else. This is unlike many of our other Woodpecker species, which are rather ubiquitous throughout the Lowcountry and coexist in separate niches.

This week for Flora and Fauna Friday we have one of our first flowers of the floodplain forest, Butterweed (Packera glabella).

Butterweed is annual wildflower in the sunflower family, Asteraceae. It is found throughout the coastal plain and piedmont of South Carolina. Butterweed is a wetland plant, typically growing in sunny, disturbed, poorly drained, fertile soils in the lower floodplains of freshwater rivers, to include areas such as fields, swales, clear-cuts, power lines, bridges, or roadsides. It can be incredibly abundant under the right site conditions. It grows from about knee to waist high, generally in disorganized clumps with a weedy appearance. Its stem is thick, ribbed, and hollow with a blush of purple-red darkening towards the base and along the ridges of the stem. Its leaves are pinnately compound with uneven, round, and toothed leaflets that expand in size as you move towards the tip of the leaf. The real defining characteristic of Butterweed, and its namesake, are its buttery yellow flowers. Butterweed bears a prolific profusion of brilliant flowers at the top of the flower stalk. The flowers have lemon-yellow petals and a rich yolk-yellow center. Each flower is about a three-quarters of an inch wide and the flower clusters are mostly flat but with a slight dome. Butterweed blooms throughout March and April, peaking at the start of April. These flowers are frequented by many species of pollinators, of all shapes and sizes.

Butterweed, and the other Ragworts in genus Packera, are avoided by White-tailed Deer and other native herbivores. This avoidance is due to their toxicity and allows Butterweed to grow more or less undisturbed. Butterweed foliage contains pyrrolizidine alkaloids, which cause acute liver damage and impair the nervous system in mammals that eat their foliage, even at fairly low concentrations. This can be dangerous to horses and cattle that are pastured in floodplain fields or fed hay harvested from these areas. So although Butterweed is an easy to grow and fairly pest-free pollinator plant, it is best kept out of home gardens, as it can readily volunteer and could become a hazard to foraging pets.