This week for Flora and Fauna Friday, we have an old world relic of homesteads past, Summer Snowflake (Leucojum aestivum).

On the eve of spring, a blaze of white over a bed of jade peppers the countryside. A vibrant life springs forth in the unlikeliest of places: the edge of a field, a roadside bottom, the corner of a lawn, or a backroad clearing. Summer Snowflake has awoken from its annual slumber. Squat bunches of narrow blue-green tongues arch out from the ground. Above them hangs a mast flying flags, six-petalled bells of white tipped in lime-green, signing across the Lowcountry the surrender of winter into spring.

Summer Snowflake is a perennial wildflower native to southern Europe. It’s a bulb plant long cultivated for its ornamental value and was spread to the eastern United States by European colonists. In Europe, its native habitat is streambeds, floodplains, and other wetland margins. In coastal South Carolina, it thrives in our warm climate and moist soils free from its native pests and predators in Europe. Summer Snowflake is what’s known as a naturalized exotic. A species that isn’t native to our region and thrives without care, but that doesn’t spread so viciously as to invade new habitats and cause harm. Summer Snowflake is far more prone to spread than Narcissus but doesn’t have the wanton wanderlust of Edisto’s African Gladiolus. It will spread into sunny wetlands but stays put on drier, sandier soils. An interesting consequence of naturalized, long-lived, stationary ornamental plants like Summer Snowflake, Daffodils, and Narcissus are that their presence often acts as an archaeological indicator. These plants were commonly planted around homes, graves, driveways, and other human structures to provide a breath of life and a symbol of civilization to generations past. Over time these structures crumble, are dismantled, and their remains swallowed by the earth. However decades or even centuries later, if they’ve not been buried beneath our maritime jungles, Summer Snowflake persists, staking out the ruins of yore and providing remembrance of peoples long since passed.

This week for Flora and Fauna Friday we have the infamous butcher bird, the Loggerhead Shrike (Lanius ludovicianus).

The Loggerhead Shrike is found year-round throughout the southern United States, including all of South Carolina. Despite its broad range, it’s a scarce bird that’s often difficult to lay eyes on. Resident birds are very site specific. Migrant individuals show up suddenly in the winter months and often vanish as quickly as they appear. The loggerhead Shrike is a large songbird, about the size of a Cardinal or Mockingbird. Their body is stocky like a Cardinal but their plumage is very similar in color and pattern to that of a Northern Mockingbird, except with greater contrast and a different hue. The Loggerhead Shrike has an aluminum-blue back and cap, white belly and throat, and a black tail, wings, and mask. More distinctly, their head is unusually large for their size and their heavy bill is sharply hooked at the tip. Loggerhead Shrikes utter a myriad of strange and unique sounds but notably all are loud, harsh, and simplistic and most call are reminiscent of either Jays or Wrens. They inhabit open habitats, such as pastures, fields, golf courses, prairies, beach dunes, orchards, and savannas. They can most often be seen perch high atop a tree or shrub or along a fence or power-line.

What’s most interesting about Shrikes, to include our Loggerhead Shrike, is that they’re a carnivorous clade of songbirds. Their diets mainly consists of large insects, lizards, and frogs but also mice, small snakes, smaller songbirds, and other small vertebrates. They scan their surroundings from up high, looking for prey, before swooping in and immobilizing their quarry by severing it’s spine with their hooked bill. Even more fascinating is that Shrikes hunt constantly and store food for future use. They take their kills and impale them on branches, thorns, yucca needles, cactus spines, or barbed wire for later use. They return to eat their meals one piece at a time. This creates quite the macabre scenery, called a “larder”, and provides clear notice for any bird watchers who wander into a Loggerhead Shrike’s territory.

This week for Flora and Fauna Friday, it’s an economic juggernaut and pollen powerhouse, Loblolly Pine (Pinus taeda).

Loblolly Pine is found throughout the southeastern United States and is ubiquitous in all but the highest reaches of South Carolina. It grows arrow-straight and can get quite tall and wide in ideal conditions. Its needles are about hand length, not too long but not particularly short. These needles skirt their narrow twigs for a foot or more down the branch, often covering the entire branch in saplings. These medium-sized needles and “leafy” branches are key to telling them apart from other pine species. Their cones are also moderately sized with sharp spines and, when dry, have a pale gray color to their exterior. These cones yield a one-winged seed, called a samara, which is blown by the wind into the surrounding area of the parent tree, or is plucked from the cone and eaten by birds and squirrels. Loblolly Pine is a generalist with rapid growth, a relatively short lifespan, ability to grow in poor soils, and tolerance for drought, flooding, and fire. Which is why it has come to be the number one timber species in all of the Southeast. It grows fast, straight, and will tolerate just about any soil long enough to make a harvestable crop of timber. This has made it the most common tree species in the modern South Carolina landscape. Nearly half the trees in South Carolina are Loblolly Pine. Yet, it was not always this way.

Historically, Loblolly Pine was found on floodplains, the margins of swamps, and other disturbed areas with moist soils. The other ecosystems of the Southeast were dominated by longer-lived or better adapted species of pine. Longleaf Pine dominated the fire-ravaged sandhills and flatwoods. Pond Pine dotted the Carolina Bays and depressional wetlands. Those same depressions were ringed with Slash Pine in the south, who also stood firm on the barrier islands. Shortleaf Pine blanketed the uplands. Virginia Pine and Pitch Pine stood upon the mountains. This left only the flood-prone fringes of rivers and swamps and other opportunistic habitats for Loblolly Pine. However, after European colonization, this ecological balance was upset. Old-growth stands of Longleaf and Slash Pine were felled and replaced with pastures and fields. Fire was suppressed on the landscape, hampering the regeneration of most Pine species, but not Loblolly. Loblolly Pine quickly colonized these disturbed areas and established a foothold in abandoned fields and windrows. When the demand for timber eventually outpaced the supply from old-growth forests, silviculture became widely profitable and the Loblolly Pine was the obvious choice for a staple cash crop in the Southeast. It has since been selectively bred to improve its form and growth rate across a wide range of soils, creating the modern Loblolly Pine that saturates the South Carolina landscape. We also have Loblolly Pine to thank for the smothering yellow fog we in the Lowcountry experience every February, as the male pollen cones of millions of Loblolly Pines simultaneously open, powder-coating our cars and waterways in pastel-yellow for weeks.

This week for Flora and Fauna Friday it’s a pair of big and boisterous black birds, our Crows of genus Corvus.

Here in the Lowcountry we have two species of Crow, the American Crow (C. brachyrynchos) and the Fish Crow (C. ossifragus). In the upper reaches of South Carolina the Common Raven (C. corax) is sometimes seen but never here in the Lowcountry. The American Crow and the Fish Crow are almost indistinguishable in appearance, both with plumage as black as coal across their entire body, a stout frame, and a sturdy, pointed bill. These two Crows constitute our largest species of Songbird in the Lowcountry and both are highly intelligent, generalists, move in groups, and have loud, distinct calls.

The American Crow is the bigger of the two, growing a touch larger than the Fish Crow. The American Crow is found throughout much of the lower forty-eight states and Canada, to include all of South Carolina. Their call is that stereotypical, repeated bark-like “Caw” we all know of Crows. However, they make a wide array of other, often strange, calls for communication with each other. American Crows are social and form tight knit family groups that move together throughout the landscape. They prefer open wooded habitats, like savannas and suburban neighborhoods, as a home base but will can be found almost anywhere and will venture into almost any habitat, to include cities, beaches, farm fields, swamps, and clear-cuts. They are extremely accomplished generalists who eat just about everything and, due to their very high intelligence, can capitalize food resources few other birds can access.

The Fish Crow is ever so slightly smaller than the American Crow and is found exclusively in the Southeast and Atlantic coastal plain of the United States. Their population numbers fluctuate throughout the year, being most abundant on Edisto Island in winter, but can be found year-round. Their calls are more simplistic but a little less consistent than the American Crow. Their calls are delivered with a distinct, nasally tone, most often as a “kah” or two-note “kah-ha”. The Fish Crow is a predominantly wetland species, being found extensively along beaches, tidal creeks, impoundments, freshwater marshes, and flooded duck fields. If you see a Crow walking on an oyster bed or foraging in a marsh, it’s almost always a Fish Crow. They’re also an expert generalist and will eat just about anything. A unique trait to Fish Crows is that they don’t form close knit family units like American Crows. In summer they pair off and raise their young, but in winter they coalesce into flocks of hundreds or thousands of birds. At dusk in winter, one can watch great rivers of Fish Crows flying west over the Island to roost overnight in the heart of the ACE Basin. They then wake in the morning, disperse, and feed across the landscape before returning again to their common roost. In early February their numbers swell in the ACE basin before the birds fly south en masse to greener spring pastures.

This week for Flora and Fauna Friday, we have a compact, clustering cousin of Carolina’s iconic palm, the Saw Palmetto (Serenoa repens).

Saw Palmetto is a small species of Palm found on the coast of the Southeastern United States, from the Mississippi River, to the South Carolina Lowcountry, and down throughout Florida. Edisto Island is on the extreme edge of its natural range, with at least a handful of healthy populations existing along the west edge of our Island. Saw Palmetto is long-lived and highly tolerant of salt, drought, and poor soils, just like Cabbage Palmetto. However Saw Palmetto does not tolerate freezing temperature well and so on Edisto Island is limited to hammock islands and other thermally insulated maritime fringe habitats. The overall appearance of Saw Palmetto is very much Palmetto-like. It has fronds with a circular blade radiating out from one central point, stringy bark, and a spherical crown. However, its fronds are much smaller than even Dwarf Palmetto and their stems are lined with sharp, hooked teeth. This makes any attempt to walk through a thicket of Saw Palmetto a dicey, and often slice-y, maneuver. Furthermore unlike our other two native Palmettos, Saw Palmetto has multiple stems, spreads clonally, and will regenerate from the roots if it’s leading bud is destroyed. This is an adaptation to the historically prevalent wildfires in Florida and the coastal Southeast. Research indicates that some clonal colonies in Florida may be several thousand years old. When not regularly set alight, Saw Palmetto grows slowly into a large bush that’s as tall as it is wide, usually about six to eight feet tall in our area. Like our other Palmettos, it blooms in spring with huge clusters of small, creamy-white flowers that are scoured for pollen and nectar by bees and other pollinators. The pollinated flowers mature into small black drupes that are eaten and dispersed by birds. You may have heard of Saw Palmetto Extract, which comes from the fruit of Saw Palmetto. (As of this writing, there is no conclusive evidence that this extract can treat any medical conditions in humans.)

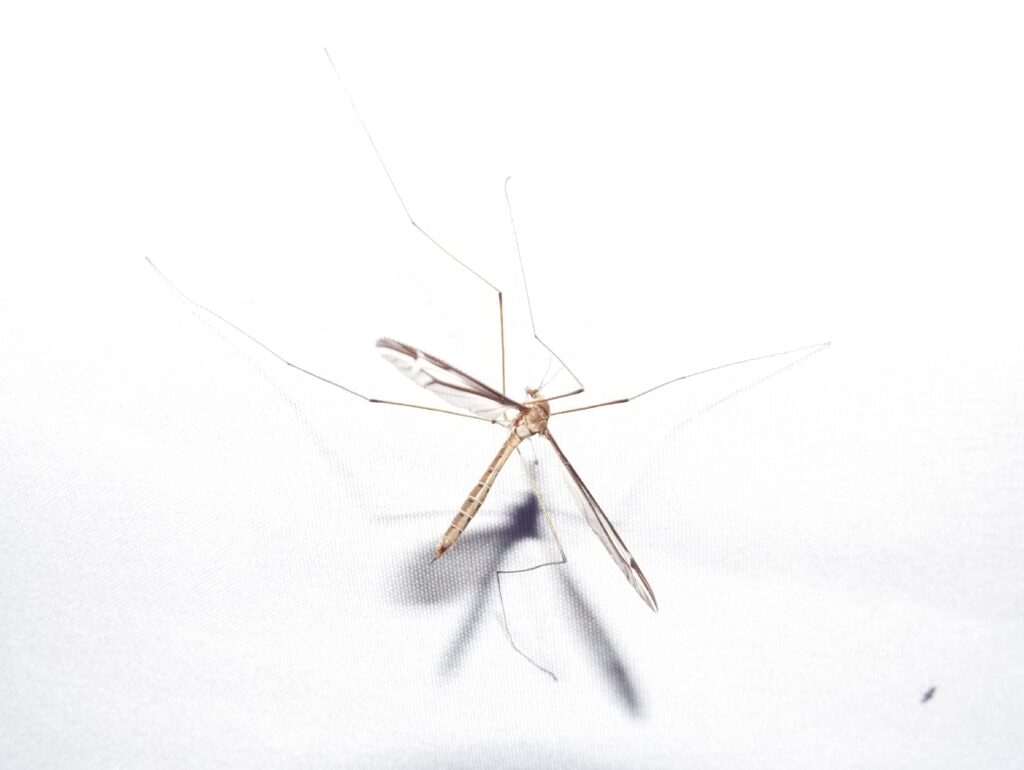

This week for Flora and Fauna Friday we have the spindly, sprawling sprites of spring, the Crane Flies of genus Tipula.

Crane Flies are true flies and in the same lineage as Mosquitos, Midges, and Gnats. They belong to family Tipulidae and today I’m focusing primarily on the members of genus Tipula. Like all Flies, they’re a pain to identify to species, so we’ll just be looking at them generically. Crane Flies are found throughout the United States. They are large, lanky flies with a long abdomen, slender legs, and narrow wings. They can be found across a wide range of habitats, particularly forested areas, pastures, and residential areas with moist soils. Crane Flies are sometimes colloquially called “Skeeter-eaters” but don’t let that nickname fool you, they don’t eat mosquitoes. In fact, most adult Crane Flies don’t eat at all and those that do, drink nectar. They’re completely harmless but can be annoying when they slip into your house through an opened door and incessantly ram themselves against a lampshade while driving your cat mad. The adult Crane Fly only lives a few days. They instead spend much of their life as a subterranean larva and then emerge as adults only to reproduce. Adult Crane Flies fly throughout the year but notably are some of the earliest flying insects to emerge, sometimes cropping up in number during warm spells amid winter. The larvae of Crane Flies are detritivores who feed on the decaying organic matter on and within the surface of the soil and on the edges of wetlands. As detritivores and herbivores, they form an important link in the food web and in nutrient cycling. Crane Fly larvae are gray, leathery, and can grow over an inch long. Notably, the larvae of Tipula Crane Flies can become an agricultural and residential pest under certain conditions. The larvae live in lawns and pastures and will feed on the live roots of plants when decaying plant matter is scarce and they will even emerge from the ground at night to feed on the leaves and buds of turf grasses, clovers, and the like. Their midnight munching leaves behind burnt-looking patches of grass in lawns. However, Crane Fly larvae present more of an intermittent, seasonal issue when conditions are right, rather than a chronic pest.

This week for Flora and Fauna Friday, we have an evergreen ornament of the winter woods, Striped Wintergreen (Chimaphila maculata).

Striped Wintergreen is found throughout the Eastern United States and across South Carolina but is most common along the Appalachians. It’s a distant member of the Heath family, which includes Rhododendrons and Blueberries. It’s a very small, perennial plant rarely ever amounting to more than a three-inch stem and seven leaves. It’s found almost exclusively and ubiquitously in the deeply shaded forest floors of upland woodlands. Striped Wintergreen gets its name from its leaves, which are evergreen, oppositely arranged, leathery with a sparsely toothed margin, and colored a dark blue-green with a thick, pale stripe down the center. Further inland, it’s one of the few evergreen plants found below the winter woods and resembles few other plants in the southeast, making it very easy to find and identify. In late May, Striped Wintergreen begins to bloom. It produces a flower stalk that nearly triples the plant’s height to a miniscule 8-inches tall. This flower stalk is thin and straight, ending in a streetlight-shaped set of arches, each ending in a single flower. These five-petalled, pendulous white flowers curl open to create an inverted bowl and are pollinated primarily by bumblebees. Pollinated flowers mature to produce a dry fruit, which is held above the plant for several months more. Striped Wintergreen is not an ecosystem defining species nor is it a species that is integrally dependent on complex mutualistic relationships with its neighbors. It’s simply a species that has done quite well for itself, living a quiet life on its own accord between the shadows of giants.

This week for Flora and Fauna Friday we have our intermediate icy-white egret, the Snowy Egret (Egretta thula).

The Snowy Egret is common year-round throughout the coastal plain of the Southern United States and also ventures further inland during the warmer months. Standing at roughly knee height, it’s pretty dead center in the size range of all our Egrets and Herons and has a lankier appearance than most. Their plumage is a uniform snow-white across its whole body but it can easily be differentiated from other white Herons and Egrets by its bill and legs. The Snowy Egret has a black bill with a patch of lemon-yellow skin in front of its equally yellow eyes. It also has black legs that end in bright-yellow feet. Both coloration combinations are unique for our local Egret species. The Snowy Egret is our most common Egret here on Edisto Island throughout much of the year. Like all Egrets and Herons, it’s an ambush hunter and, like most, it hunts fish, crustaceans, amphibians, and aquatic insects. Snowy Egrets are most often spotted patrolling the banks, shallows, lagoons, and marsh edges of our tidal creeks, shifting locations as the tides change. However, they can be found in a wide array of brackish and freshwater systems. Snowy Egrets tend to be more sedentary than some of our other medium-sized Egrets and will often be spotted posting up motionless at the mouths of small gullies, tributaries, and culverts. During spring, their breeding season begins and mature birds will disperse to large multi-species rookeries further inland. Breeding plumage Snowy Egrets will display delicate, long plumes from their back and elongated plume-like feathers from their head and throat. Their feet and eye-patch can also become orangey-pink. The plumes of the Snowy Egret were highly sought after for the millinery trade in the late 1800s, which resulted in huge population declines for the Snowy Egret and many other wading bird species. This severe market hunting pressure and species decline was one of the catalyzing factors for wildlife conservation laws in the early 1900s and resulted in the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, which prohibited the hunting of most of our native bird species and allowed Snowy Egret populations to fully recover to where they are today.

This week for Flora and Fauna Friday, we have a pair of tree species that help define some of our most iconic Lowcountry ecosystems, the Bays of genus Persea.

Here on Edisto Island we have two species of Bay, Redbay (Persea borbonia) and Swamp Bay (Persea palustris). Both species share many similar physical characteristics. However, the two species differ most notably in their habitats. Redbay is predominantly found in maritime forests on barrier islands and sparsely in maritime fringe forests on our sea islands on the wet but well-drained soils possible with our unique geology. Swamp Bay is found in stagnant, freshwater wetlands on acidic, poorly-drained soils. They are particularly abundant in Carolina bays and are the source that lent these isolated wetlands the “bay” name. They can also be differentiated by their twigs, with Redbay having smooth twigs and Swamp Bay having fuzzy twigs. Both teeter somewhere between a small tree and a large shrub, Swamp Bay tends to be more tree-like and Redbay shrubbier. Yet the two are more similar than different, in fact they were lumped together as one species until recent decades. Our Bays have somewhat blocky, light-gray bark and usually a gnarled or kinked stem. Their evergreen leaves are narrow but close to hand length with a glossy, dark-green upper surface. Both bloom in mid-spring with small pale yellow-green flowers and bear an egg-shaped dark-blue drupe. Both of our Bays are also the primary host plants for the Palamedes Swallowtail and can host the Spicebush Swallowtail too. The Avocado (P. americana) is a tropical member of the Bay genus but not native to the United States.

Our Bay trees are in trouble, particularly Redbay. Redbay has long been feeling the impacts of coastal development, as its barrier island and maritime fringe habitats have been rapidly developed over the last century. Swamp Bay has a much wider distribution and has been secure from such pressures. However, early in the 2000s an exotic pest carrying a pathogenic fungus was introduced from Asia and has been ravaging native populations of Bay trees since. A miniscule female Redbay Ambrosia Beetle locates a healthy Bay tree and bores a hole into its living wood. This beetle carries a pathogenic fungus called Laurel Wilt which is deposited by the beetle during the wood boring process. The beetle and the fungus have a symbiotic relationship. The beetle and its larvae feed on the fungus as it spreads throughout the tree and, in exchange, the fungus inoculates the beetles with spores and is spread deliberately and directly to the sapwood of new host trees by dispersing female beetles. The life cycle of the Redbay Ambrosia Beetle is fascinating but ultimately spells doom for infected Redbay and Swamp Bay trees, with infected stems dying within a matter of months. Infected trees can be identified by fine tubes of sawdust emerging from the trunk and dying trees are easily recognized by sudden wilting and browning of foliage across entire limbs or whole crowns. This disease affects not only our native Bay species but also other members of the Laurel family, including Sassafras, Spicebush, and Avocados. It is now becoming a serious economic threat to Avocado orchards in south Florida.