This Week for Flora and Fauna Friday we have the crown jewel of the swamp, Virginia Iris (Iris virginica).

Through the columns of Gums and over the foundation of muck a twinkle of violet shifts under the weight of a Darner. Dangling over a palisade of emerald blades a crown of color beckons. Swallowtails and skippers flutter and flee from its fringes amidst the darting strikes of darners and skimmers. Behind the bulwark flies the standards of its colorful comrades, rising above their verdant outpost. An encampment of Virginia Iris in the barren mire of the swamp.

Virginia Iris is a large species of wetland wildflower found throughout our coastal plain. It grows through its roots into spreading clumps, shin-deep in water on the fringes of permanent, shady wetlands. It’s large, flat grassy-leaves reach waist height as they arch upward and outward from the water in overlapping fans. In April they send up stalks to bear their flowers. Palm-sized, six-petalled, multi-colored, double-decker flowers primed in white, painted in violet, accented with saffron, and inlaid with veins of crimson. These flowers act as beacons not only for the curious naturalist but for the wandering insect. Pollinators, still groggy and ravenous from the prior season’s sleep, flock from across the swamp to this chromatic café, some sipping their first nectar for the year.

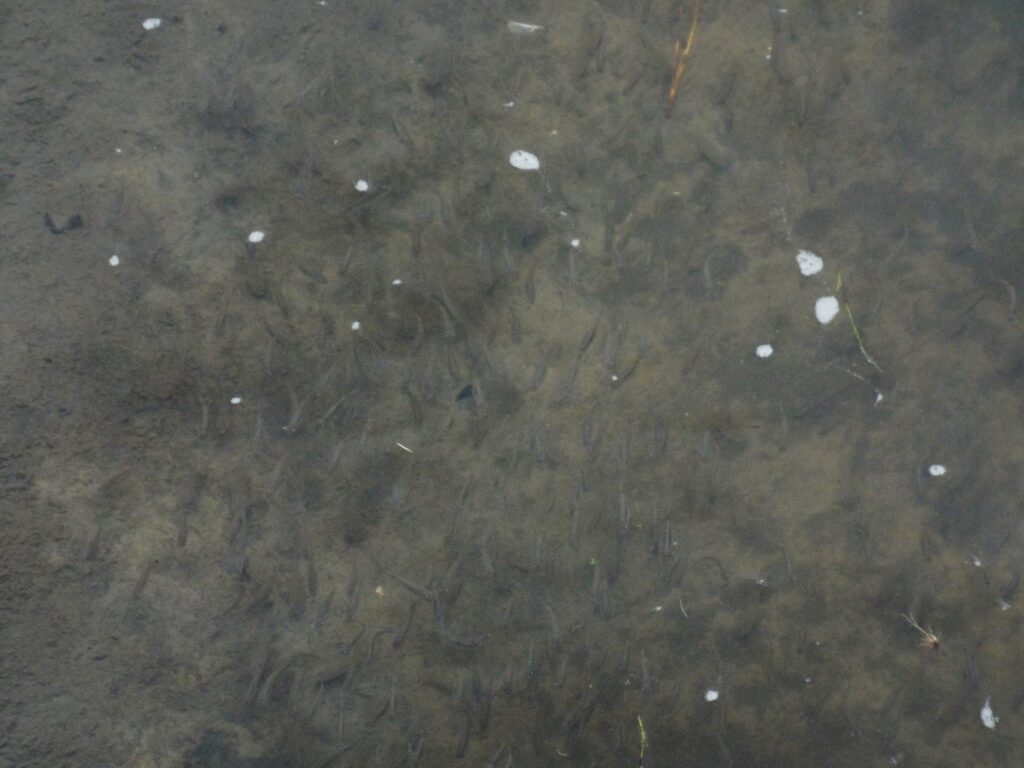

This week for Flora and Fauna Friday we have the unkillable Killifish and the fodder of fishermen, the Mummichog or Mud Minnow (Fundulus heteroclitus).

The Mummichog is a member of the Killifish, which used to be one family but is now several. Just know that this group is composed mainly of species of small fish. Our species is indeed small, about the size of a finger. Their scales are the color of our creeks, a murky greenish-brown above, which fades to a beige below. Their bodies are lightly iridescent and often accented down their side by a dozen or more thin silvery lines. Their body is stubby, their fins are round, and their face is blunt and upturned. Mummichog are found in tidal habitats throughout the seaboard of the Eastern United States and are as common as pluffmud in the salt marshes and estuaries of South Carolina. These Mud Minnows can be found along the edge of every creek and tributary on Edisto Island. They are most known for their value as bait fish because not only are they easy to catch but they’re incredibly hardy. Their value as a bait hints at their two most important characteristics. Mummichog are a critical link in the food web of the salt marsh. They are a primary prey item throughout the year for a long list of species including Egrets and Herons, Blue Crabs, Terns, Mink, Kingfishers, and an uncountable number of fish species. The Mummichog themselves feed on small arthropods, detritus, and larval fish.

In fact, Mummichog are world renowned for their ability to survive the harshest of chaotic environmental conditions and have been used widely as a scientific model because of it. I’d even say they top the Mosquitofish in the environmental survival department. Mummichog can survive not only the wild temperature swings of salt marsh shallows but also the anoxic conditions of stagnant wetland pools, the high toxin loads in polluted waterways, and, most impressively, rapid fluctuations in salinity. Salinity in the salt marsh can vary massively. Some shallow areas can become practically freshwater following heavy rains and others near the coast can be close to oceanic saltiness. Salinity plays a critical role in the biology of aquatic organisms. To briefly summarize, freshwater species are constantly trying to keep salt in their bodies and excess water out. Conversely, marine species are continuously pumping water in and salt out. Plop one in the other’s environment and it’s disastrous for their biochemistry. Fish that live in brackish environments, like some areas of the salt marsh, all naturally have a resistance to these fluctuations and some can slowly shift between the two. Mummichog live on the edge, quite literally the edge, or fringes, of the marsh, and as such can experience these shifts in salinity at the drop of a hat, and tolerate them. They have even been known to colonize freshwater ponds as escaped bait.

This Flora and Fauna Friday it’s an understory florally whorlly pendulous tubular wildflower, Woodbine or Coral Honeysuckle (Lonicera sempervirens).

Up the Wax-myrtle, over the Yaupon, onto the Sweatleaf, and into the Oak the Woodbine climbs. A peeling varnished bark falls back to make way for the ever reaching pastel-pink of a new year’s growth. Wavy glaucous leaves stretch out in the sun as a stem above pushes onward and upward, leaves pulled tauter to this tower with every story added. Atop the tip the leaves become a dish and a coral crest protrudes. At the summit of this upcoming summer’s solar array blooms this spring’s flowers. A stack of whorls extends its soft red fingers until they burst forth with five-petalled tips dusted with the yellow of pollen.

Woodbine is a perennial woody flowering vine in the Honeysuckle family. It’s found throughout South Carolina and the Eastern United States. It prefers sandy soils and full-sun but is most often found in partial-shade along forest edges, where it has something to climb. It is not a particularly high climber but can topple any shrub or sapling it encounters. Its bark is thin and shaggy and its vines fairly fine. New growth is often tinged in red and leaves have a bluish cast. Leaves are oppositely arranged and become perfoliate, wrapping around the stem, as they near a flower bud. Flowers are long, narrow, coral-red, and bunched together. The blooms peak in April but can continue through summer. A combination perfect for hungry Hummingbirds. The fruit is a small red drupe that is eaten and dispersed by birds. Coral Honeysuckle is an excellent addition to most any backyard garden. It can be trellised to produce shade and provides food for both birds and butterflies.

This week for Flora and Fauna Friday we’re bob-bob-bobbing along with the American Robin (Turdus migratorius).

The American Robin is our largest member of the Thrush family as well as the strongest contender for most common bird in North America, with a population estimated at over 300 million. He sings a jarring fluty tune through a carrot-orange bill while his salt-and-pepper beard shudders to keep the beat. Dark glassy eyes look out beyond his perch through broken white eyeliner on a carbon-black head. His shale-gray back reflects a wisp of the morning sun and a red rusting chest puffs out with a gulp of brisk spring air. The male Robin in his territory is a handsome and familiar site across the country. His feminine counterpart is not as contrasting or vociferous as she bobs through the stalks of a dewy pasture’s hedgerow, beak stacked with inchworms. Both make their way to Edisto each year at the dawn of fall with scores more couples in the wing. They mingle with the local for the winter before fleeing from the summer’s sweltering heat.

American Robins are primarily a migratory species, returning to the South for every winter, but can be found year round in certain sections of our state. They’re most easily found in wet lawns, field edges, and the understory of moist forests as they loose their windy tune and short step across the ground. American Robins live on a diet of arthropods and fruit. In the winter their diet is primarily fruits, including holly, crabapple, and redcedar. As the spring approaches and the weather warms, they shift their meals to earthworms, spiders, and inchworms. Robins are best known for their habit of bobbing along as they search for snacks and collect longitudinally extended critters in their mouth. Many songbirds can’t walk and can only move on the ground by jumping due to how their leg tendons are shaped. However, Robins are one of the species that can walk just fine, they just choose not to a lot. You’ll oft see them sprint short distances on open ground. The bobbing helps Robins move in tall grass, as they jump from footing to footing. The worm hoarding is for efficiency’s sake. This is simply so mothers don’t have to make so many trips to and from the nest. It also guarantees they have enough pureed worms to go around for the little ones.

This week for Flora and Fauna Friday it’s another subterranean parasitic plant, Bearcorn (Conopholis americana).

Bearcorn, AKA Squawroot or American Cancer-Root, is a non-photosynthetic, parasitic, subterranean angiosperm. Much like Indian Pipe, which I’ve written about before, it lives its life entirely underground and is only visible when it blooms. However, unlike Indian Pipe, Bearcorn blooms in spring rather than fall and it belongs to a different family of plants, Orobanchaceae. This family of plants is well known for their ability to parasitize the roots of other plants, Bearcorn being no exception. Bearcorn is holoparasitic, meaning it survives entirely from parasitism and its cells contain no chlorophyll. However, unlike Indian Pipe, it parasitizes other plants directly rather than indirectly through the mycorrhizae. Bearcorn taps directly into the roots of an Oak tree, specifically one of the Red Oaks, and siphons off both calories and nutrition while forming a root gall underground. In early spring, Bearcorn blooms with a cluster of flower spikes, thick and creamy-yellow in color. These flower stalks are short and cone-shaped. Their resemblance to tiny corn cobs and palatability to wildlife earned them that common name of “bear corn”. The flower stalks can persist for several months and eventually wither into a dry brush-like shape. This makes it easier to detect for several months after but the flower’s full display is only short-lived.

This week for Flora and Fauna Friday we have the high-flying harbinger of spring, the Purple Martin (Progne subis).

The Purple Martin is found throughout the Eastern United States and is our largest species of Swallow. Like all our Swallows, they feature long, pointed wings, a streamlined body, a small beak, and short, delicate legs. However, unlike our other Swallows, they’re of a stockier build and darker complexion. Purple Martins get their name from the plumage of the male who is drenched from beak to rump in metallic indigo feathers and fringed by semi-gloss black flight feathers. Females are not as striking, with their beige bellies beneath dusky gray backs, but still stand out on the wing. Purple Martins are a fair bit larger and usually a shade or many more darker than our other Swallow species, making them easy to identify in the air. Even so, you’re more than likely to hear them before you see them. Their sky-high chaotic song composed of bubbling electronic samples is hard to mistake for anyone else. Purple Martins are insectivores. They eat insects of all shapes and sizes and catch all their food on the wing. Martins snag their to-go orders by skillfully employing their impressive speed and agility. Swallows are some of the fastest and most maneuverable bird species there are and their large, broad mouths help funnel in prey. They even drink while flying by skimming the surface of the water.

Other than the purplish plumage, the big thing that sets Purple Martins apart is their proclivity for colony nesting. A few Purple Martins begin arriving in the Lowcountry from their wintering grounds in South America in about mid-February. These early birds, nicknamed scouts, are older adults returning to their prior haunts. Over the coming weeks, the remaining birds trickle in in increasing numbers and begin to establish that year’s breeding colonies. These colonies can be anywhere from a handful of birds in a single house to several hundred across a property. It really just depends on housing if the habitat is good. Martins can be defensive and are known for dive bombing people or predators who get too close for comfort. Purple Martins now nest almost entirely in artificial nestboxes in the Eastern United States. Originally, Martins were cavity nesters that used old Woodpecker nests. Yet, they’ve now urbanized to preferentially inhabit avian apartment complexes of hollow bottle gourds and claustrophobic condominiums. Interestingly, this shift occurred only in the last few hundred years and has become a permanent fixture of their ecology. Native Americans erected Martin-houses using bottle gourds prior to the arrival of European colonists. Their reasons for doing so aren’t understood but the Martins took kindly to the gesture nonetheless. Later, colonists emulated the Native American practice and apparently appreciated the beautiful bubbly birds as well. Before long, much of the Martin’s natural nesting habitat had been destroyed by logging and the birds became dependent on artificial nests. Nowadays, not only do they nest entirely in nestboxes but, when given the option, Martins actually prefer nesting near human activity rather away from it. If you’re interested in making friends with Martins, consider erecting a Martin house for next year. They love open fields, ponds, and singing to their ground-dwelling neighbors.

This week for Flora and Fauna Friday we have a widespread spreading shrub that’s all the rage this time of year, Blueberries, genus Vaccinium.

Blueberries are a diverse genus of bushes native to the Southeast. The genus of Vaccinium includes not just Blueberries but also Cranberries and Huckleberries as well as the locally native Sparkleberry bush. Here in the Lowcountry, we have about eight species that can be considered proper Blueberries, at least one Huckleberry, and the aforementioned Sparkleberry. The Blueberry genus belongs to the Heath family, Ericaceae, which includes many of our most popular southern shrubs, such as Azaleas, Rhododendrons, Mountain Laurel, and Fetterbush. Heaths as a whole are gnarled growing, laterally spreading, acid soil loving bushes with spring flowers and a thicket forming nature. Blueberries tick all of those boxes but are not as extreme as many of their relatives.

Blueberries grow in forested habitats on a wide array of acidic soils all across South Carolina. Spreading from fire scorched savannas, up ravenous hillsides, over barren sandhills, and into stagnant Carolina Bays you can rarely go far in our state before running into a Blueberry of some shape or form. Blueberries can differ a great deal in appearance between the different species. Some species form low, expansive thickets only a foot or two above the soil while others crawl along the ground like a vine and yet more climb ten-foot high above the forest floor. However, all share similar traits in their leaves, their stems, their flowers, and, of course, their fruits, which distinguish them as Blueberries. All our Blueberries have small, simple leaves with a slightly leathery texture and of a paler hue of green erring on the yellow side of the spectrum. Some species are evergreen, some deciduous, and some can’t make up their mind. On top of that, they have green stems that can turn orange or red on one side when exposed to light. Regardless, their wiry, twisted growth and loose thicket arrangement are usually enough to discern their lineage while wandering the woods. Another more telling character is in their flowers: small porcelain-white urns, blushed with pink and overturned to spill their scent upon the twilight of winter. Of course, following the flowers is their namesake blue berries. The size, quality, color, timing, and flavor of our Blueberries runs the gambit between species. Some are small, dark, late, and tasteless. Others big, blue, early, and sweet. Just a handful are small, blue, late, and rich in a deep flavor that can only be ascribed as “Blueberry”. All are round and either a powdery blue or deep bluish-black in color. For the record, practically all of our cultivated Blueberries here in South Carolina belong to one of two species: Southern Highbush Blueberry (V. formosum) and Northern Highbush Blueberry (V. corymbosum). Both species are very similar, forming tall bushes that produce plentiful large fruits. They’re so similar in appearance that they used to be considered the same species. The two are both native to our area but Southern Highbush Blueberry is the more common wild plant here in the Lowcountry.

This week for Flora and Fauna Friday we have a spindly spidery critter with a superstitious reputation, the Harvestmen of order Opiliones.

Harvestmen are arthropods with quite the folklore surrounding them. I can recall quite a few childhood tales about them. Chief in my memory is how they’re supposed to be the deadliest spider around, save that their fangs are too small to puncture your skin. In contrast to this playground lore of yore, I’m here today to tell you the truths about this interesting arachnid.

Harvestmen belong to the order Opiliones within the Arachnida class. They share no close relation with spiders and are actually most closely related to Scorpions. They’re common throughout our forests and woodlands and often found huddled together in shady crooks of porches and barns. Although they come in many shapes and sizes, their general appearance is distinct and unmistakable. I won’t even pretend that I comprehend their diverse phylogeny but I believe the genus Leiobunum is the clade most of us will recall when imagining the Harvestmen of the Lowcountry; a round pale-brown body composed of a single segment supported in midair on eight articulated wispy legs. Each barely bristle-thick appendage arcing upward from the fringes of that egg-shaped center. Peering ever closer we can see a tiny cluster of beady little eyes front and center, on what passes for a head, and a pair of tiny pincers for a mouth.

Harvestmen move with either a jittering, bouncy gate or a slow purposeful walk, elongated middle limbs out stretched ahead as they feel their way forward. They have a wide and varied diet that differs between species. Most are omnivorous, some are predatory, and others scavengers. They eat their food, alive or dead, animal or vegetable, by picking it apart with their tiny pincer-like mouthparts. Harvestmen are wholly nonvenomous by the way and completely harmless to humans. However, they will release foul smelling chemicals if handled roughly. They also employ autonomy to escape from danger, shedding their wiry legs if they become ensnared. This is a costly move as Harvestmen cannot regrow their limbs and is why you’ll often find them down a leg or two.

This week for Flora and Fauna Friday we have an almost evergreen understory addition to our upland woodlands, Sweetleaf (Symplocos tinctoria).

Sweetleaf, also called Horsesugar, is a large broadleaf shrub native to the Southeastern United States. Sweetleaf is an important addition to our forest ecosystems here on Edisto as it makes up a significant portion of the understory in mature upland forests around the Island. Both of its common names reference the palatability of the leaves to horses and livestock. Some say you can taste the sweetness yourself by breaking the main vein of a fresh leaf and touching it to your tongue, but I’ve never been able to taste it and Lord knows I keep trying. The specific epithet “tinctoria” means dye and the bark of the plant was once used for making a yellow dye.

Sweetleaf grows a distantly liana-like trunk sheathed in pale gray bark, mostly smooth but periodically split with furrows of cinnamon. This lumber lattice lauds large elliptic leathery leaves of emerald green, often weeping wearily when wanting water. These leaves are somewhat evergreen, as some plants will keep their leaves throughout the winter while others shed them all in fall. For as common as Sweetleaf is, its ubiquity and rather generic appearance can make it unsuspectingly difficult to identify if it’s not already on the mind. The easiest time to pick it out is in late winter. About the start of March Sweetleaf starts to bloom and its scant branches begin to glow with fuzzy flowers of cream-white and gold. Sweetleaf is one of our first flowers of the year and this final frost flush helps wake our pollinators from their winter slumber. Those flowers mature into a small, and otherwise insignificant, drupe.

Another easy way to identify Sweetleaf is by a fleshy gall that often afflicts the plant. This gall is caused by the bacterium Exobasidium symploci and it appears on Sweetleaf twigs. The gall is usually silvery blue over a lime-green base color with a rubbery, foam-like appearance. This gall is a physical mutation caused by the Exobasidium bacterium growing within the leaves or flower tissue of the shrub. These galls are generally not a health concern for the plant. However, their alien appearance in often impossible to ignore for those on an idle amble. They stand out like a sore thumb in the barren winter woods.

This week for Flora and Fauna Friday, we have a pair of fluffy butted, big eared, garden guests: the Cottontail Rabbits (genus Sylvilagus).

Rabbits as a whole belong to the order Lagomorpha. Lagomorphs share some superficial similarities to Rodents, as the two orders are closely related, but they’re distinct clades. One of the simpler ways to tell the two orders apart is that rodents have two incisors and rabbits have four. Here on Edisto Island we have two species of rabbit, both of which are members of the Cottontail genus. Both of our rabbits are roughly the size of a football and about the same color. They both inhabit early successional habitat, prefer to feed on fresh vegetation on the edge of open areas, and are most active at night. Rabbits are herbivorous, feeding mainly on forbs. Like White-tailed Deer, they are a prey species and, similarly to deer, rabbits have a physiology built for detection and fleeing. Rabbits have big side-facing eyes and movable cupped ears for sensing predators. These are coupled with long, muscled rear legs that allow them to accelerate rapidly to high speed in order to escape predators. This is why rabbits never tend to stray far from thickets or other dense cover.

The Eastern Cottontail (Sylvilagus floridanus) is your common rabbit found in a wide range of habitat throughout the eastern half of the United States. They’re most often found in fields, yards, roadsides, and other open habitats. They have a brindled coat of white, tan, and black fur, large beady black eyes, tall elliptical ears, and a conspicuous cottony tail. In general, they have a round shape to their head and a somewhat boney appearance. The Marsh Rabbit (Sylvilagus palustris) is found throughout the coastal plain of the southeast and is partial to marshy wetland habitats. They are quite common on the Sea Islands in maritime forests surrounding tidal marsh. Marsh rabbits have fur that is brindled primarily in browns and black, small eyes, short circular ears, and they like to keep their tail tucked away. Marsh Rabbits usually have a triangular-shaped head and a plump, guinea-pig-like appearance.