This week for Flora and Fauna Friday we have an aggressive and expansive wetland plant critical to our Island: Black Needlerush (Juncus roemarianus).

Black Needlerush is a member of the Rush family, Juncaceae. Rushes are one of the big three “grass-like” families, along with the Sedges of Cyperaceae and Grasses of Poaceae. The quick trick to telling these three apart are their stems. Grasses have flat leaves, Sedges triangular stems, and Rushes tubular leaves. As we all know, biology is the study of exceptions to the rule. So this quick trick can get you quickly tricked, but it at least holds water for today’s Rush.

As stated, Black Needlerush looks similar to a grass but has tubular leaves. These perennial leaves are often three to four foot long and dastardly sharp. Walking unprepared into a sea of Needlerush is never a pleasant experience. Plants grow in bunches and spread laterally by rhizomes. Needlerush blooms in spring to produce an open, palm-sized cluster of mahogany-brown seed capsules. Black Needlerush is the other half of the tidal tag-team that makes up our salt marsh. Smooth Cordgrass tackles the low marsh and Black Needlerush takes the high marsh. Black Needlerush grows naturally in massively expansive single species meadows across sandy marsh lands and salt flats of the Lowcountry. Needlerush grows on higher elevations than Smooth Cordgrass but often in soils just as saline. It grows on the firm sandy substrate rather than the nutrient fluff that is pluff mud. Its perennial nature provides a more permanent home for our marsh birds and rodents during winter. Its tightly woven leaves create a natural sieve to filter and collect eroding soils and tidal flotsam as well as break apart storm surges and wakes.

This week for Flora and Fauna Friday we have a pair of personable Parids: the Carolina Chickadee (Poecile carolinensis) and the Tufted Titmouse (Baeolophus bicolor).

Today’s Titmouse and Chickadee are both members of the Tit family, Paridae, and the only members of said family found here in the Lowcountry. Parids as a whole are small, vocal, social songbirds that inhabit woodlands. This is a description that fits our two birds perfectly. Chickadees and Titmice can be found living in small social colonies wherever trees abound throughout the state of South Carolina. They’re regular neighbors in the backyards of suburbia and staple feeder birds. Both eat a varied diet consisting primarily of insects and seeds.

The Carolina Chickadee is a minute monochrome bird. A small ball of clearly sectioned ivory, coal, and gunmetal with a short beak and round head, they’re hard to mistake for anything else. The Chickadee’s namesake alarm call of “Chick-A-Dee-Dee-Dee…” is far more slurred than the onomatopoeia leads you to believe but is nonetheless distinctive. The Tufted Titmouse is a small, subdued plumage songbird with a small pointed crest for a touch of flare. Their belly is a dingy white and their back an aluminum-gray with subtle chestnut flanks below their wings. Their “Peter-Peter-Peter” song can be heard ringing clearly through the hollow winter canopy. Both species are found throughout our woodlands on Edisto. Chickadees seem to me tolerant of planted pine and swamps and Titmice more plentiful in dense forests. The two species are non-migratory and nest in cavities. Chickadees and Titmice are curious creatures. They will often go out of their way to come fuss at any people or predators they feel are intruding on their turf. Sometimes drawing in a crowd of nearby songbirds who want to know what all the hubbub is about.

Resident Titmice and Chickadees are what are known as a nuclear species to bird watchers. During fall migration, mixed flocks of migratory songbird species move through the Lowcountry. They feed while snaking through the treetops on their journey south. Nuclear species, like our little Parids, attract these mixed flocks. Like tourists stopping to grab a bite and chat with the locals, these migrants collect around and tag along behind a Parid colony briefly before hopping back on the highway in the sky. Because of this, birders like to keep a watchful eye on flocks of Chickadees and Titmice in the hopes that a mixed flock will drop in to say hello.

This week for Flora and Fauna Friday we have a carpeting coastal wildflower: Indian Blanket (Gaillardia pulchella).

Indian Blanket is a species better known generically as just Gaillardia. It’s a low growing wildflower in the Aster family, Asteraceae. It’s soft, seafoam foliage bubbles up from the sand beneath as it spills onto a dune side. Floating up between these leaves light burning pinwheels of flame. A roaring disc of color over a bleak landscape that hovers and flickers on the seabreeze. Indian Blanket is one of our few wildflowers so specialized for our sandy shores. It’s a common sight razing the lots and lawns along Palmetto Boulevard as it consumes the sand and flicks tongues of color into its own updrafts.

Gaillardia is a curious and carefree wildflower that appears to grasp no concept of the seasons. It blooms chaotically and constantly throughout the year and never rests but finally. It is truly neither annual nor perennial and seems to choose it’s time and place to perish of its own accord. Sometimes it sprouts in fall and blooms in spring, other times the opposite. Typically neither but never predictable. It is a statistical plant that must be spoken of in generalities and assumptions for looking at the individual for answers yields none of use. Although it places such emphasis and effort into its floral art it invites few visitors in for exchange. Scarce nectar and sparse pollen entice few but the most mundane of neighbors as their petals pyre and roar to our attention. It is a true artist in its field, absorbed and isolated in its own methods, reveling in the craft of its creation and seeking no approval of others. Its work is meant for its own joy and not for ours. What significance we gleam is but coincidence for it seemingly exists merely for the sake of it.

This week for Flora and Fauna Friday, we have a high-waisted, rattling, regal angler wearily watching us: the Belted Kingfisher (Megaceryle alcyon).

The Belted Kingfisher is a stocky, compact bird found throughout the continental United States. It’s the only member of the Kingfisher family with a substantial range in our country. They can be found in the Lowcountry for most of the year but vanish in spring only to return in mid-summer. Belted Kingfishers nest in caverns that they tunnel into the side of river bluffs. When breeding season rolls around, they mostly leave our relatively level coast to head for more exaggerated geology further inland.

Kingfishers are about a foot in length with a robust build, blade-like bill, and a tall cranial-crest of feathers. Their mantle and mask are a watery shade of aluminum-blue that wraps across the breast and extends down to the flight feathers. Their primaries and tail feathers are a slate-gray and checkered by bars of white. In contrast to their dark backs are their icy-white bellies. Like their fellow angler the Osprey, female Belted Kingfishers sport a ruddy-brown waistband across the upper belly. The call of our Kingfisher is a loud rattling cry of rapid, aggressive, low-pitched squeaks. They issue this distinctive call universally in response to all manner of disturbances, be they greeting a mate, defending territory, or alerting to danger. Belted Kingfishers are notoriously hard to approach but easy to spot and observe from a distance.

Belted Kingfishers are piscivorous. They eat almost exclusively fish. In our tidal creeks, the ever present Mummichog is most often their target. Kingfishers hunt by sight. They perch atop a tree limb, shrub, or dock and scan the water for anything fishy. When something catches their eye, they burst from their perch and ascend into a hovering flight above their target. They linger in the air for a moment before diving headlong into the surf. With a splash they split the water, stabbing or snapping their bill into any unsuspecting fish that crosses their path. Using their natural buoyancy, they pop back to the surface and clap their wings against the water to launch themselves back into the air, returning to its preferred perch to enjoy a meal with a view. Kingfishers swallow their prey whole. So they make sure to thoroughly wallop their unlucky catch against their perch before gulping it down, bones and all.

This week for Flora and Fauna Friday we have a pleasant, laid back late season wildflower: Camphorweed (Heterotheca subaxillaris).

Camphorweed is a bushy perennial wildflower partial to sandy open habitats and found throughout the southern United States. It loves to grow in fallow fields, abandoned lots, roadsides, and beach dunes. It’s even a plentiful component of our wildflower meadows at the Hutchinson House. Camphorweed grows well where many other plants struggle to survive, making it a welcome addition and burst of color on many an idle acre. The flowers of Camphorweed are about three quarters of an inch in size, yolk-yellow, and with an unremarkable aster-like appearance evenly spaced across the surface of the plant. As its appearance suggests, it is a popular plant among pollinators. Although its flowers are rather run of the mill, the foliage helps define this plant from its peers. The foliage of Camphorweed is a silvery, bluish-green. The leaves themselves are roughly triangular, covered in a fine coat of hair, and, lacking a petiole, cling directly to the stem. Overall the plant has a very coarse, scraggly appearance in my experience. Although, its growth form is quite variable. Most often on Edisto it can be seen as a short bush but it can also grow as a small forb or a tall, organized stalk. As the name suggests, the plant contains camphor oil. Camphor is the compound that gives Vicks VapoRub its signature scent. However, Camphorweed does not contain its namesake chemical in any substantial amount. So the scent is fairly faint.

This week for Flora and Fauna Friday it’s everyone’s favorite bivalve, our snotty Lowcountry delicacy: the Eastern Oyster (Crassostrea virginica).

Our Eastern Oyster of the Lowcountry is a translucent, salty morsel sandwiched between two razor sharp shells of calcium-carbonate, one freely flapping and the other glued permanently into an amalgamated cluster of other Oysters. Our Oyster is found only in saline waters and is a bivalve just like a mussel or clam. Oysters are notable for their behavior of spitting at low tide. It’s a behavior that’s purpose is not well known but whose tune is trademark to our creeks; a melodious nasty habit of a dirty habitat. They attach to structures as free-swimming larvae and grow larger year after year, layer by layer. Overtime, more oysters cling to the oldest oysters as the community develops into a cluster. The cluster sheds and blossoms as it expands into a reef and eventually a bed in a larger system of beds that blanket the banks. These beds are centuries old and litter the shores of our rivers and creeks throughout the Lowcountry.

The Eastern Oyster is not just delicious, it’s an ecosystem engineer. A species of such utmost importance that its mere existence brings wealth and health to the environment surrounding it. Oysters are sessile. They swim through the water as larvae before attaching to a structure and staying put. The favorite thing for an Oyster larva to stick to is another Oyster. This makes good sense. Oysters can’t move so if it sticks to another Oyster, it’s probably someplace where an Oyster can live well enough. This tendency to self-adhere creates an oyster reef, a piling up and accumulation of decades of Oyster shells along the bank of a tidal river or creek. Spires of bleached shells tile and summit over each other above a foundation of pluff mud. These oyster reefs are critical habitat to many of our estuarine species. Stone Crabs, Mummichog, Terrapin, and an untold variety of fry nestle into this limestone mountain at high tide; its jagged peaks and deep ravines warding off the predators that encircle their retreat.

Oyster reefs not only nurture life on their shoulders but shape the very terrain around them. Oysters are filter feeders, they inhale surf filled with silt and plankton, strain it through their bodies, and exhale clean water. This filtration acts to do two things of great benefit to us. It removes potentially harmful bacteria from the water column, that the Oyster then eats, and sequesters sediment onto the Oyster reef. Oysters eat plankton, which is a catchall term for little critters that float in the water and can’t get around too good. This includes harmful bacteria, like fecal coliform, that we pollute our waterways with. However, Oysters don’t eat sand, silt, or most detritus. So they spit that out, where it falls into and behind the oyster reef. This serves to clear the water and build up the bank of the creek beneath and behind the oyster reef. This effect is strengthened by another passive effect of oyster reefs, wave-breaking. Oysters reefs are large, broad, vertically chaotic structures made of mortar that functionally act as a breakwater. Boat wakes and windblown waves crash and shatter against the oysters, scattering the sediment they carry behind the shells. Over time the bank builds up behind the oyster reef enough that the Smooth Cordgrass can send down its roots to stabilize it. The Oysters and Cordgrass work in tandem to close that gap and solidify the stream-edge against erosion.

This is why restoration and proper management of our oyster beds is critical to the health of our tidal creeks. Oysters clean the water of harmful contaminants that close our fisheries and restrict swimming. Their reefs buffer the pluff mud against boat wakes and storms, protecting and bolstering the Cordgrass that protects us from storm surge. Oysters need other oysters to establish and thrive. If we degrade our oyster beds with unsustainable harvesting and boat traffic, then that supply will evaporate in short order.

This week for Flora and Fauna Friday is the slithering fear of fishermen, the Cottonmouth (Agkistrodon piscivorous).

The Cottonmouth, or Water Moccasin, is a modestly sized viper at up to three feet long and fairly bulky. Their scales have a corrugated, studded appearance that takes on a deep brown coloration in adults. In contrast, younger snakes show disorganized lighter bands of tan or greenish-brown that contrast their umber scales. Cottonmouths are an aquatic snake prolific in our freshwater rivers, streams, ponds, swamps, ditches, and marshes across the Lowcountry. They’ll also patrol soggy fields and wet meadows in search of a meal. Their favorite foods are fish and frogs but they’ll eat birds and rodents when given the chance. Unlike Copperheads, Cottonmouths will gladly make their presence known when they feel threatened. They’ll coil their bodies to face the trespasser, vibrate their tail, spit a sickening hiss, and throw open their jaws to flash a palate of ghostly white gums. The contrasting blink of white signals their discontent and is usually sufficient to let most mammals know to back off.

A Cottonmouth’s preference in most cases is to remain motionless to avoid detection. If that fails their next course of action is to escape to the nearest body of water. Cottonmouths are clumsy on land but masterful swimmers; if they can swim away they will. Confrontation is used as a last resort when cornered or startled. However, they are not ill equipped for a fight as their bite is venomous and more potent than their coppery cousin. If you encounter a venomous snake in the wild, the best course of action is to leave it well enough alone. The number one cause of envenomation is attempting to move or handle a viper. They’d rather not waste their venom on you to begin with, you’re too big to eat. So to alter an idiom, let coiled snakes lie.

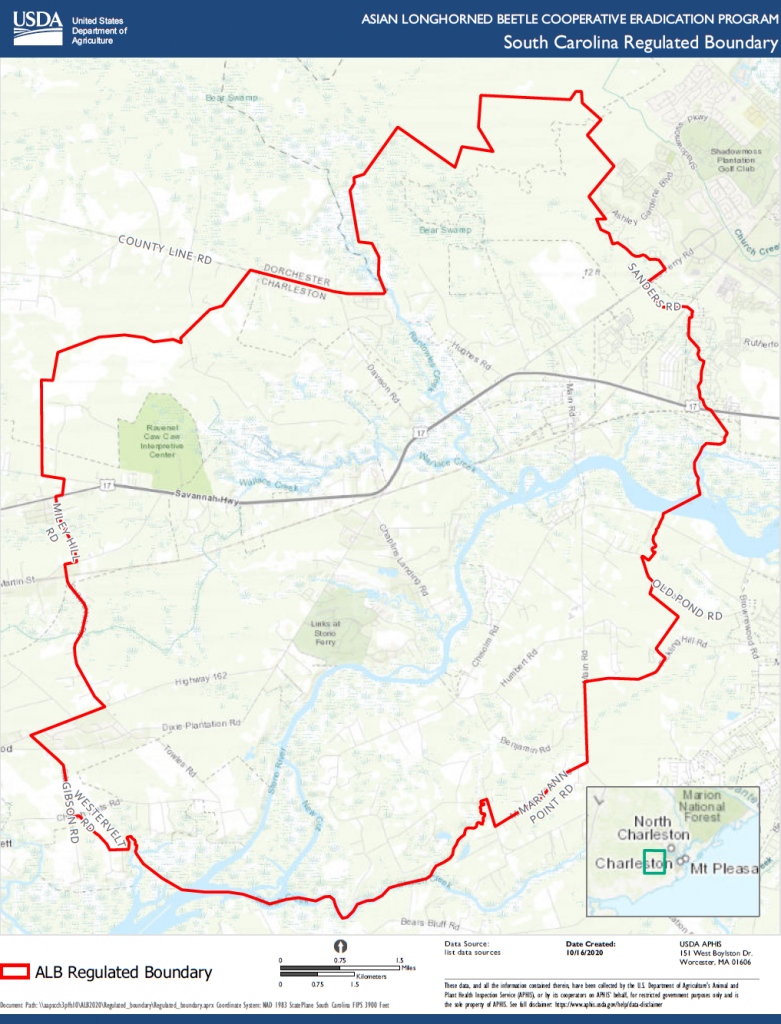

As you may have heard, the Asian Long-horned Beetle (Anoplophora glabripennis) was recently discovered for the first time in South Carolina. The species is a native to Southeast Asia. It first appeared in the United States in 1996 in Brooklyn, New York followed by Illinois in 1998, New Jersey in 2002, Massachusetts in 2008, and Ohio in 2011. In June of 2020 it was discovered in Hollywood, SC. Biologists suspect the infestation has been ongoing for five or more years. So far, more than 2,000 trees have been confirmed to be affected in Ravenel, Hollywood, Meggett, and Johns Island. The infestation appears to be centered on Rantowles and Stono Ferry, encompassing more than a 3-mile radius.

The Asian Long-horned Beetle is an invasive species of insect. Its larvae feed on the wood of native trees, leading to the structural collapse and eventual death of those trees. As a non-native exotic, the beetle has few natural controls and the trees lack sufficient defenses to fight the beetles. This can result in the beetles spreading unchecked through the ecosystem, destroying forests and altering habitats permanently. This potential for uncontrolled growth and ecological damage is what defines the species as an invasive and what makes its discovery so alarming.

The primary larval host plant for Asian Long-horned Beetles here in the Lowcountry is by far Red Maple (Acer rubrum). Red Maple is a native tree that is extremely common in our forested wetlands, bottomlands, and river floodplains. Red Maple is also used extensively in suburban landscaping. The beetle will feed on other tree species as well including Ash, Willow, Elm, Birch, Cottonwood, Sycamore, and possibly Tupelo. They are not known to infect Oaks or Conifers, including Pine. Biologists fear that the beetles will escape into the remote bottomland and floodplain forests surrounding Ravenel. Here they will be much more difficult to control and they may make the jump into infesting Tupelos. The uncontrolled destruction of the Maples and Tupelos of our bottomland forests would be devastating for one of the most critical ecosystems here in the coastal plain of South Carolina.

The adult beetles are metallic blue-black, covered with white spots, and an inch or more in body length. They are quite large and have black and white banded antennae longer than their body. Female beetles leave behind distinct marks on the bark of trees when laying their eggs. Females chew a shallow 3/4 inch scar in the tree’s bark, nicknamed a “cigar burn”, and lay an egg inside. The newly hatched larvae first feed near the surface of the trunk before moving into the heart of the tree. Wood of infected trees can be identified by the finger-width tunnels the larvae leave behind inside the wood. Adults emerge in summer, leaving a deep and perfectly circular half-inch hole in the side of the trunk.

However, all is not lost! The USDA, Clemson University, College of Charleston, and the SC Department of Natural Resources are making a serious and concerted effort to eradicate this dangerously invasive beetle from the South Carolina Lowcountry for good. The College of Charleston’s Stono Preserve was one of the first confirmed sights of Asian Long-horned Beetle in the state and they are working to facilitate the USDA’s establishment of a quarantine headquarters on the property. The USDA and Clemson University are jointly working to assess the scope of the infection and are drafting quarantine protocols and regulations for the area. SCDNR is proactively surveying all Red Maples on their 690-acre Dungannon Heritage Preserve, which is located in the heart of the infestation. The USDA was previously successful in eradicating the Asian Long-horned Beetle from New Jersey, Illinois, and much of New York and Massachusetts. There is still a good chance we can nip this problem in the bud before it gets out of control, especially with your help.

You too can help control the spread of the Asian Long-horned Beetle. Together we can stop it from ravaging our native ecosystems! First and foremost, if you see an adult beetle or the distinct marks they leave behind on host trees, report it to the USDA’s APHIS or Clemson Extension immediately! (Contact info below.) They’re the experts on handling this pest and they’ll know what to do. Other than that, the best thing you can do is not transport firewood or woody yard debris out of or within the infected area. Asian Long-horned Beetle larvae may be living inside of the wood and, if brought out of the quarantine area, can emerge to infect new areas of our state. The adult beetles only emerge during summer, do not live very long, and don’t move very far during that time. By not transporting wood within the infested area, we can drastically reduce the chances of live beetles escaping quarantine and destroying habitat in the surrounding coastal communities, such as Edisto Island.

Further reading on the Asian Long-horned Beetle:

USDA: THE LATEST NEWS ON THE ASIAN LONG-HORNED BEETLE

CLEMSON: MORE INFORMATION ON THE BEETLES IN SOUTH CAROLINA

Where to Report Asian Long-horned Beetle sightings:

Call the USDA at: (866) 702-9938

Contact Clemson: (864) 646-2140 or invasives@clemson.edu

Article by: Tom Austin, Land Protection Specialist for EIOLT

Photos by: Steven Long, Clemson University, Dept. of Plant Industry

Greetings from the EIOLT Education Outreach Committee! We have another learning opportunity for your presented by one of our local experts in the field.

In our third episode of Conversations in the Field, Melinda Hare is joined by local biologist and EIOLT’s very own Land Protection Specialist, Tom Austin. Tom explains the importance of grassland ecosystems to agriculture and the environment here on Edisto Island and in the surrounding Lowcountry. Tom also shines a light on what EIOLT is doing to conserve the gorgeous wildflower meadows at the Hutchinson House.

We hope you enjoy this informative presentation on a topic seldom covered.

Greetings from the EIOLT Education Outreach Committee! It’s time for another learning opportunity with one of our local experts in the field. In our second edition of Conversations in the Field, join EIOLT Board member and Master Naturalist, Lindsey Young, as she takes us on a special kayak trip through Big Bay Creek and the surrounding creeks on Edisto. This is your chance to learn about the variety of shorebirds that are often seen around our waterways as well as one of our local favorites – the Atlantic bottlenose dolphin.

If you’ve been stuck inside and want to experience the zen of a peaceful paddle on the water, this conversation about creek life is for you!