This week for Flora and Fauna Friday we have a genus of flowering plants quite unlike anything else in the Lowcountry, the Yuccas of genus Yucca.

Yuccas, often called Spanish Bayonets, are common throughout the coastal plain of South Carolina and one species, Yucca filamentosa, is found all the way into the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains. Members of the genus are easily identified by their blue-green, strap-like leaves that narrow to a folded point, singular stem, and summer blooms that bear head-high flower stalks dangling dozens of fist-sized, pendulous, ivory-white flowers. All species are evergreen, drought tolerant, and bloom during the heart of summer. Yuccas have robust root systems and, unlike Palmettos, will propagate clonally and regenerate if cut down.

On Edisto we have three species: Moundlily Yucca (Yucca gloriosa), Aloe Yucca (Y. aloifolia), and Adam’s-Needle (Y. filamentosa); each is more of a generalist than the last. Moundlily Yucca is fairly uncommon but easily found across the dune systems and barrier islands of Edisto. Its growth is relatively low and its leaves are relatively broad with smooth edges. Aloe Yucca is found across the Sea Islands of the Lowcountry and several miles inland. They have a tendency to clump together and have tall, erect growth habit that produces a spindly trunk beneath. Their leaves are long, narrow, and wield vicious terminal spines and a hacksaw inspired leaf margin. Aloe Yucca also produces a fruit, purple-green and reminiscent in shape to an overinflated baby-banana, which is said to be edible. Yet I can tell you, from personal experience, that that is up for debate. (To me it tasted, after baking, like wet slimy starch and burnt coffee grounds.) Adam’s-Needle is by far the most common Yucca in the state. It can be found from the blistering dune-scapes of the Atlantic Coast to the shadowed rain-slick slopes of the Blue Ridge. It grows low to the ground and often with company. The margins of its stiff, glaucous leaves fray away to leave telltale silver curls down their length, making it the easiest Yucca to identify by far.

This week for Flora and Fauna Friday it’s the symphony of the South, the orchestra of the orchard, and the chorus of the forest: the Annual Cicadas, specifically genus Megatibicen and Neotibicen.

I’m sure you’ve heard before about the mass emergences of Periodical Cicadas (Magicicada spp.) that occur at regular but lengthy intervals. Here in South Carolina we only have one brood of 13 year Cicadas to speak of for that genus (Brood XIX). Unique as they may be, we’re not talking about them today because they’re not found on Edisto Island. Today we’re discussing the Annual Cicadas found throughout the Lowcountry, specifically the large bodied species of Megatibicen and Neotibicen. These species can be painfully hard to differentiate. So we’ll just discuss them at the generic level.

The Annual Cicadas, as the name suggests, come out every year to serenade us with that white noise wailing synonymous with southern summer. A sound to clog our ears like the humidity smothers our skin and the sun sears our eyes. Annual as they may seem, the species does not complete its life cycle in a single year. Each annual emergence only represents a subset of the population. The nymphs live underground for several years where they feed on the sap of tree roots. In the heat of summer they crawl a short ways up a tree trunk into the steamy air to begin their terminal molt. Their exoskeleton splits along the back and a squishy green adult Cicada emerges. The adult lingers as it flushes its wings and solidifies its skin before climbing out of harm’s way to complete the transformation. Left behind is the exuviae, or shed exoskeleton, of the nymph. This shed is usually a translucent yellow-brown in color and, though delicate, will remain clamped to bark or a wall until dislodged and then appropriately repositioned on the t-shirt of an unsuspecting friend. Adults come in many colors and patterns but most are a complex, cryptic blend of browns, greens, blacks, and grays. Their body plan, however, is fairly consistent. A chunky two inch long teardrop-shaped body, long diamond-shaped wings, large spherical eyes set wide on a rounded face, and a mask-like “mouth” of horizontal ribs. Adults feed like their larvae on tree sap, except they eat the above ground kind.

The song of the Cicada is their mating call. Males produce a loud vibrating call using organs on the abdomen called the tymbals. The tymbals are a pair of membranes near the base of the abdomen that the Cicada vibrates rapidly to produces a sound, which then resonates through their body and bounces off their perch to project their voice into the air. In concert, their calls can be deafening beneath the boughs of a shade oak. Females can call as well but reserve their voice for defense, screaming if slighted to startle would be predators. Despite their willingness to be heard, Cicadas are often difficult to find with the eye. Their cryptic colors, static habits, and preference for perches around the tree canopy can make it hard to lay eyes on one, even when you’re trying. However, look not and they seem to fall, almost quite literally, into your lap whirling with a chattering screech.

This week for Flora and Fauna Friday we have a strange stickish sticking plant, Devil’s-Walking-Stick (Aralia spinosa).

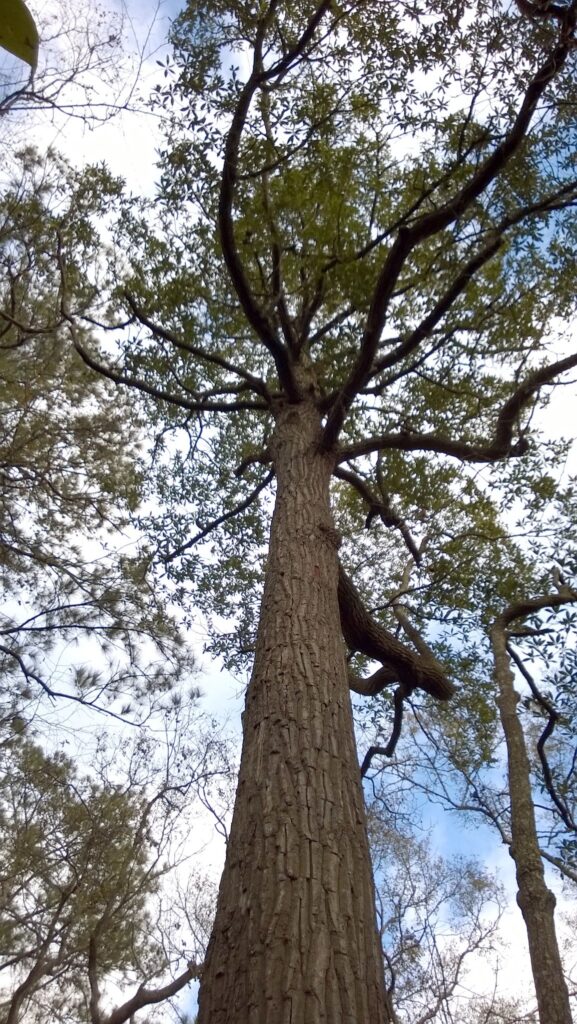

Devil’s-Walking-Stick is an interesting woody plant that grows throughout the Southeast. It’s found in a wide range of understory habitats with variable soils but it does best in moist, rich soils. It spreads clonally by its roots and, when given space, to form thickets in the understory. This plant produces a single, perfectly straight, narrow stem with a fairly consistent diameter. Each year this stem grows taller but hardly any wider, producing no branches even as it stretches past twenty feet in height. That stem is ringed in projections and prominences of prickles all along its length. Most notably, its buds produce a gnarly ring of painful pokers at a regular interval. This is where the colorful colloquial common name comes into play. The stalk is thin, straight, and tough, giving it the ideal features of a walking stick. Yet its bark is so thoroughly armed as to thwart that thought against further consideration. It’s also important to note that Devil’s-Walking-Stick is deciduous. So in winter it reduces its profile down to nothing more than a mere twig until spring.

In stark contrast to its fence-post physique, each year’s fresh growth produces an umbrella of gargantuan, tri-pinnately compound leaves. Each leaf being two feet in width and sometimes twice as long! In truth, they’re the biggest leaves native to the whole United States. In summer their canopy is capped in a profusion of pale-green flowers at a foot or more in diameter. Over the next month or so the flowers set fruit and ripen into a stalk straining haze of glistening purple-black drupes. These fruits are adored by birds and the flowers that preceded are often enveloped in swarms of pollinating insects. These features make Devil’s-Walking-Stick a worthwhile addition to most any pollinator garden or wildlife friendly yard.

This week for Flora and Fauna Friday we have a prolific songbird of both marsh and farm, the Red-winged Blackbird (Agelaius phoeniceus).

A sharp “chek” cracks the air before a torrent of bassy buffeting floods the ear. A rolling cloud of undulating black hoists itself out of the marsh and onto the horizon. Waves and ribbons of sporadic shadows twist and break over the canvas of the sunset. Birds in bulk escape their roost and whisk themselves away into the curtains of twilight. The ascent of a murmuration of Red-winged Blackbirds is a universally awe inspiring event. From a totally unseen position hundreds, thousands, on ten-of-thousands of birds rise into the air in one continuous stream. They darken the sky and smother the senses in a captivating display.

The Red-winged Blackbird is an especially common songbird year-round throughout the wetlands, farmlands, and marshes of the Lowcountry. They can be found in numbers of any scale, from a single soul to the uncountable murmurations of the marsh. Salt marshes and farm ditches are probably the easiest places to spot them. They’re not hard to spot either, as males love to perch atop a stalk of grass or fence post and blurt their curt calls and aggressively bubbling song at any and all who will listen. The male is stately and handsome; brilliant saffron fringed ember-red shoulders blaze down in contrast to his umbral plumage, shadowed by the blue of the sky. Females are much more practically plumed, with brindled walnut and cream and gildings of gold on a penumbral black base. Red-winged Blackbirds feed mainly upon the ground eating seeds and grains as well as an unlucky arthropods they descend upon. A Female Red-wing builds her nest by weaving grasses together around the stalks, blades, and branches of vegetation, creating a funnel suspended in the air. As a species, they prefer to nest above water in marshes but will just as readily spin a cradle over the drainage ditch of a promising corn field.

This week for Flora and Fauna Friday, we have another ubiquitous but unimpressive weed that I feel we all could overlook less, American Burnweed (Erechtites hieraciifolius).

American Burnweed is a rather tall and rather narrow native annual wildflower. It’s partial to sunny sites on a wide range of soils. It most often appears on roadsides, field edges, forest clearings, and other areas where the soil was recently disturbed or the canopy suddenly opened. This is where it garnered the moniker of “Burnweed” as the plant is quick to populate fire-scarred landscapes. Often many plants will grow together into dense clumps. Each plant usually grows to four to six feet in height with a single straight stem. The leaves are long, lance-like, and very variably serrated. The stems are finely ribbed and coated in fine hairs. Overall the plant has quite the unkempt appearance. The flowers are shaped like an oil lantern and rather inconspicuous, with nothing but a wash of creamy yellow and a few flecks of pink on the tip to distinguish them from the lime-green foliage. The flowers, interestingly, are primarily pollinated by wasps of all shapes and sizes. Flowers mature and unravel into a sphere of silky seeds that further frays and floats away in the currents of the breeze.

This week for Flora and Fauna Friday it’s the hoppinest amphibian this side of the Savannah, the Southern Toad (Anaxyrus terrestris).

The Southern Toad is one of four species of Toad found in our state. Of those four, the American Toad (A. americanus) and Fowler’s Toad (A. fowleri) are fairly similar in appearance to the Southern Toad but only found in the upstate. That leaves the Oak Toad (A. quercicus) as our only other Lowcountry Toad. However, those are found almost exclusively in sandy pine forests and are significantly smaller with a prominent yellow dorsal stripe. This leaves our Southern Toad as an easily identified and ridiculously common amphibian member of our Lowcountry fauna.

The Southern Toad is generally two to three inches in length with warm-brown skin mottled by darker spots that are studded with warts. Yet, their skin tone is highly variable and takes on any shade between brick-red, straw-yellow, concrete-gray, and mocha-brown. They have stumpy legs and a squishy, potbelly appearance. Their brow is strong and their mouth wide, sandwiching their large eyes between. Eyes with horizontal pupils and a gold-leaf iris. Their skin is thick, dry, and textured rather than the gossamer, smooth, and clammy skin of frogs. This allows them to better retain water and live in far drier habitats. Southern Toads can be found throughout the Lowcountry in a wide variety of habitats. However, Toads are still dependent on external moisture and high humidity to survive and they require standing water to spawn.

Males Toads are smaller than females by a considerable degree and can be identified by their dark throats. That distinctive throat hints at its extra ability. Male Toads, like frogs, have an expandable throat that they use for acoustic amplification. When singing, their throat inflates like a balloon as they spew their rolling droning tone along the water’s shore. Southern Toads are known for spawning in mass groups in late spring following a heavy rain that was preceded by a dry spell. Hundreds of Toads will congregate in the nearest ditch, pond, or wetland at dusk and summon a deafening chorus that lasts for hours, with waning encores abounding the rest of the week.

Southern Toads are mainly nocturnal and burrow under logs or leaf litter during the day. They are predatory and subsist off a diet of invertebrates. They catch their meals with their extendible, sticky tongue. It’s not a very long tongue but they can move it at impressive speed, lunging their body forward and flinging their tongue in a whip-like motion. Conversely, Southern Toads are an important food source for many of our terrestrial predators. They are a staple in the diet of snakes and herons. However, Southern Toads are also poisonous, which provides some protection against predators. Their poison is concentrated in their paratoid glands. These are the two kidney bean shaped lumps behind their eyes. When agitated, Toads will secrete a toxic substance from these glands onto their skin in an attempt to poison and deter predation. They’re harmless to humans when handled. Just don’t rough one up and then lick your fingers.

This week for Flora and Fauna Friday we have the gem of the murky mire, the Ebony Jewelwing (Calopteryx maculata).

Fluttering on translucent onyx wings and shimmering in a metallic aquamarine the Ebony Jewelwing is the crowning beauty of our damselflies. Males appear cloaked in a reflective foil of deep blue-green that gives rise to wings so thoroughly dark as to at first appear opaque. Females are less reflective along the body but are indeed the namesake sex for the species, with wings a smoky ebony-black and encrusted with a snow-white stigma. They’re one of our largest species of Damselfly, reaching three inches in length. The species is common throughout the Eastern United States and can be easily found almost any time of the year down here in floodplain forests, bottomlands, stream sides, and practically any shaded wetland. Jewelwings are predatory, feeding mostly on mosquitoes and flies.

Damselflies are a close relative of the Dragonflies. As the name implies, they are less voracious and robust than their larger cousins but share many similar characteristics, like elongated bodies, narrow wings, and large spherical eyes. Damselflies generally have a svelter, more delicate appearance and prefer to hold their wings vertically and tilted back. Most notably, they are not as agile or active of a flier as Dragonflies, preferring to flutter and float rather than hover and dart.

This week for Flora and Fauna Friday we have a powerfully poisonous wetland wildflower, Spotted Water Hemlock (Cicuta maculata).

Spotted Water Hemlock is a tall stringy wildflower native to the United States and found extensively throughout both the Lower Forty-Eight and the Lowcountry. It loves perpetually wet and somewhat sunny soils, usually right on the fringes of permanent wetlands. The plant can grow to a respectable eight feet in height and has large, highly divided, compound leaves. Its stem is hollow and streaked with vertical purple lines. It is rhizomatic and perennial, spreading slowly along the wetland edge and returning year after year. It blooms in early summer, producing many umbels composed of hundreds of small white flowers.

Spotted Water Hemlock’s most noteworthy characteristic is neither its size nor its flowers, it’s a chemical in its flesh called cicutoxin. This chemical is found in all parts of the plant but is most concentrated in its roots. It’s a neurotoxin and its potency has won Spotted Water Hemlock the title of most toxic plant in North America. Normally this poison wouldn’t be much of a problem for people as most folks don’t eat random plants they find growing in a ditch. However, this Hemlock is a member of the Carrot family, Apiaceae, and is similar in appearance to several edible wild plants. As a result, a case of mistaken identity with this wildflower is most often fatal. I won’t go into details but it’s an unpleasant way to go.

The week for Flora and Fauna Friday we have a petite and precocious songbird: the Blue-gray Gnatcatcher (Polioptila caerulea).

The Blue-gray Gnatcatcher is our only representative of the Gnatcatcher family here in South Carolina. The Gnatcatchers are most closely related to Wrens. The Blue-gray Gnatcatcher is found throughout the eastern United States and all of the Palmetto State. They’re most common throughout the warm seasons but are a year-round resident in some corners of the Lowcountry.

Blue-gray Gnatcatchers are, simply put, a wee little bird. It’s not as wee as a Hummingbird or Kinglet, but it’s sufficiently small enough to fit the bill. Their plumage is a cool white beneath with a back a shade between aluminum-blue and gunmetal-gray. A black tail with white corners and a heavy white eye-ring supply the needed accents. Males take a bluer hue in breeding season and year-round they wear a black unibrow, giving him an expression of perpetual irritation. Blue-gray Gnatcatchers have an active lifestyle and, much like Kinglets, seem to be in perpetual motion. They bounce and bound between bushes, calling all the while. Their call is a nasally plaintive whine. It’s hard to describe but easy to recognize. Blue-gray Gnatcatchers are gleaners, they move from plant to plant, branch to branch, leaf to leaf in search of any opportunities for nutritious morsels that may present themselves. Their diet consists entirely of invertebrates, but only small ones.

Their preferred habitats are moist broadleaf forests but they can be found in a broad range of ecosystems and forest types. Gnatcatchers nest in trees by building a camouflaged cup to cradle their eggs. Their nest is small, compact, cozy, and anchored to a tree branch or crook with a copious amount of spider webs. The nest is constructed of moss and grass and lined with fuzzy seeds, animal hair, and feathers. It is all then glued together with spider silk. To help blend in with the bark background, the nest is then plastered in a layer of lichen, matching it perfectly to the surrounding lichen lined limb.

This week for Flora and Fauna Friday we have a unique and beautiful tree of the flatwoods: Loblolly Bay (Gordonia lasianthus).

Loblolly Bay is a member of the Tea family, Theaceae, and the only member of its genus found in the United States. Loblolly Bay is found across the coastal plain of the Southeast, from North Carolina to Alabama. Loblolly Bay thrives in the acidic, saturated, and poorly drained soils of our flatwoods and Carolina bays. As such, it is locally common throughout the Lowcountry where there habitats are found.

What distinguishes Loblolly Bays from our other hardwood trees is in its bark, foliage, and, most notably, its flowers. With age the bark of Loblolly Bay becomes deeply furrowed in long vertical ridges. Canyons of carmine or gulleys of gray; bark color is variable in various environments. Its leaves are reasonably sized and evergreen, a deeply enriched emerald delta beneath the basin of the bark. Floating upon this verdant expanse shines a flora flotilla. A quintessentially Tea patterned perfect flower reminiscent in size and position to a Magnolia. Five fuzzy petals of simple whiteness ring a basket of golden anthers. Much like the unrelated Southern Magnolia, this tree can reach an impressive size and its brilliantly colorless flowers act as beacons to beckon insects and admiring eyes. Flower appear at the eve of the summer solstice and linger for the following weeks.