This week or Flora and Fauna Friday, we have a lavish lavender limbed local shrub to discuss. We’re shining a spotlight on the American Beautyberry (Callicarpa americana).

American Beautyberry is found throughout South Carolina. From the Appalachian foothills to the barrier islands of Edisto. Its appearance is open and spreading with large, opposite, simple leaves. The bushes can reach head height but are usually about chest high. Beautyberries are often found growing along forest edges or beneath trees in open forests, yards, and fields. In the early summer, American Beautyberry produces clusters of small, pale pink flowers at the nodes below the bases of its leaves. By late summer, these nodes are bursting with rich lavender berries.

American Beautyberry is a hardy native shrub that makes for a great ornamental. Their flowers, while small, do attract a number of pollinators. The vibrant purple fruits remain on the plant for weeks, providing not only a treat for the eye but a treat for many species of birds. Northern Mockingbirds are a particular fan of the berries and a major disperser of their seeds. When crushed, the leaves of the plant release the chemicals callicarpenal and intermedeol, which can act as a mosquito and tick repellent.

This week for Flora and Fauna Friday, we’ll be talking about an insect from an order that we’ve yet to discuss, but you’ll hopefully be seeing more of them in the future. This week we’ll be looking at our first Dragonfly, the Eastern Pondhawk (Erythemis simplicicollis).

Eastern Pondhawks are one of our most common and widespread dragonflies here in the lowcountry. They can be found along almost every quiet body of fresh or brackish water. I’ve seen them along ditches, ponds, lakes, wetlands, rivers, lawns, creeks, floodplains, retention ponds, impoundments, ephemeral wetlands, and marshes. Eastern Pondhawks are a medium-sized dragonfly. Larger than our Dashers and Dragonlets, smaller than our Skimmers and Darners, and somewhere in the middle of the size range for our Pennants. Males are a powdery blue throughout the body and females sport a lime green thorax with a black and white striped abdomen. Both sexes share the characteristic clear wings, green head, and white abdomen tip of the species. The species also has a habit of landing on the ground or as low as they can on vegetation. This makes them an easy species to identify.

Like all dragonflies, the Eastern Pondhawk has an aquatic nymph. A wingless first stage of life for living underwater. Dragonfly larvae are accomplished hunters. They possess a hinged, extendable lower jaw that they use to grab prey. Once the nymph is fully grown, they climb up a stem, branch, pole, or wall near the water and begin to molt. From the shell of this nymph will emerge an adult dragonfly. This process may take an hour or more to complete. Dragonflies are ancient and accomplished hunters. Their aerial agility is surpassed only by Hummingbirds. During the day, Eastern Pondhawks feed on flying insects like mosquitoes, flies, moths, butterflies, lacewings, and even other dragonflies.

Surprise! I’ve got a biology bonus post for ya’ll. It doesn’t pair with tomorrow’s Flora and Fauna post at all but it was too cool not to share.

Last Friday out at the Hutchinson House, I noticed something strange poking through the brush pile in the front field. There was a Crape-Myrtle blooming in the middle of it! The strangest part about that is there was never a Crape-Myrtle planted in that spot. It was a regularly disked and bush-hogged field before we acquired the property. When the EIOLT began cleaning up around the Hutchinson House we piled the woody debris we cleared in the middle of the field, so it would be out of the way of construction and could eventually be disposed of. Last fall, we cleared a strip out in from of the house so the footers for the cover could be poured and the boom lifts would have level ground to work on. On the far end of that strip was a large Crape-Myrtle stump that had been choked by Chinese Wisteria until it was just barely clinging to life. The inside of the stump was totally rotten and what was left of the tree was too far gone to make a proper recovery. So we had it removed and it ended up in the brush pile with the other debris. Eight months later, that same nearly dead stump, ripped out of the ground and left in a pile in the middle of a hot sandy field, is not only still alive but doing well enough to bloom! On top of that, what’s left of its old root system is putting out shoots where the stump was torn out. You just can’t kill a Crape-Myrtle.

This week for Flora and Fauna Friday, we’re looking at another common wildflower of SC. This week we’re examining Meadow-beauties, genus Rhexia.

Meadow-beauties are a genus of low growing, wildflower shrubs common to the savannahs, fields, roadsides, glades, and meadows of the south. Each of our common species are similar in appearance. They sport four wide magenta petals and eight finger-like anthers of pollen above opposite, simple leaves. Meadow-beauties produce very little nectar, so they don’t draw in many butterflies or wasps, but their ample pollen supply is a magnet for native bees. Their flowers are rather ephemeral and only last a short while before their petals are shed. Beneath the flowers, an urn-shaped capsule full of miniscule seeds forms.

Around these parts, I’ve stumbled upon three species of Meadow-beauty: Maryland Meadow-beauty (Rhexia mariana), Handsome Harry (R. virginica), Maid Marian (R. Nashii), and Savannah Meadow-beauty (R. alifanus). Maryland Meadow-beauty is by far the most common and can be found across Edisto and SC as a whole. It loves roadsides, fields, and meadows. It grows as a short, open shrub and can also be found as a white-flowered variety. Handsome Harry is more suited to pine savannas and shows up more inland. It’s just as short a shrub as the others but with much fuller foliage. Maid Marian is mostly coastal and prefers wetter soils. It looks a lot like Maryland Meadow-beauty but is given away by special hairs on the back base of its petals. Savannah Meadow-beauty is easy to pick out from the others because of its smooth, blue-green leaves held upwards against its stem. Its flowers are a little larger and more vibrant than the others and the plant thrives in sandy Pine savannas.

This week for Flora and Fauna Friday, we’re taking a look at another unmistakable bird of Edisto. This week we’re talking about the Painted Bunting (Passerina ciris).

The Painted Bunting, just like the Roseate Spoonbill, is an unmistakable sight in the Southeast. A blur of color that streaks along the hedgerow and launches in through your peripheral vision. They were even given the French nickname of Nonpareil, meaning “without equal” or “unrivaled” in reference to their striking plumage. The male is a vibrant patchwork of red, blue, and chartreuse. The female a blend of greens and yellows not seen on any other bird in our region. They are roughly sparrow sized and relatives of the Cardinal and Tanager. Painted Buntings eat seeds and insects. They often visit bird feeders in their territory. Their preferred habitats are maritime forest, agricultural fields, and the shrubby edges of causeways, roads, and forests. Females build their nests in dense scrub a few feet off the ground or in Spanish Moss well out of reach. Males mark their territory with a warbling song they sing from an exposed perch, usually about 30ft above the ground. Painted Buntings are here most of the year but vacation in Mexico for the colder parts of winter.

This week for Flora and Fauna Friday, we’re looking at grassy wetland plant whose appearance betrays its heritage. This week we’re talking about the White-topped Sedge (Rhynchospora colorata).

The White-topped Sedge is a resident of wet meadows, ditches, and other open shallow wetlands. (It’s even growing in the ditches across the street from the EIOLT office.) It grows in dense strips or clumps that reach about 2 feet tall. In late spring, the Sedges bloom producing a small cluster of white flowers ringed by a pale corona of long, variegated bracts. Bracts are the leaves found just below a flower. In the White-topped Sedges, these bracts are up to 6 inches long, white at the base, and green at the tip. They form a whorl beneath the true flowers where they resemble petals, much like the bracts of Dogwood or Hydrangea flowers.

White-topped Sedges are interesting because they’re a member of the Sedge family, Cyperaceae. Sedges are an incredibly diverse group of plants that are closely related to, and strongly resemble, Grasses. Just like Grasses, Sedges are rather plain and their flowers mostly inconspicuous. The white-topped Sedges are an exception. They’ve developed a showy flower unlike any of the members of their family. These white bracts standout like a beacon to insects and attract pollinators to the plants. As the pollinators move from flower to flower, they distribute pollen between flowers. Almost all the other members of the Sedge family rely on wind pollination, making the White-topped Sedge’s adaptation unique among Sedges.

This week for Flora and Fauna Friday, we’re discussing the hot-pink ladle-faced wading bird that draws birders from far and wide to the ACE basin. This week we’re taking a gander at the Roseate Spoonbill (Platalea ajaja).

It’s unquestionable. Roseate Spoonbills are the most striking of all our wading birds. Their hot pink wings, bubblegum legs, bony spoon-shaped bills, large stature, and glowing ruby eyes will give even the most seasoned birder whiplash when one turns up unexpectedly. No other bird, save a very lost Flamingo, commands the same presence in the marsh. Despite their resemblance to Wood Storks, of the species in SC, Roseate Spoonbills are most closely related to Ibis.

Roseate Spoonbills are quite common in coastal TX and LA as well as southern Florida but are a much more special sight on Edisto. They migrate our way come summer, trickling in along the intracoastal waterway. We’re only just on the edge of their breeding range in SC. So most of the birds you will see are immatures coming more north than the breeding grounds to feed. Adult Roseate Spoonbills have a bald head but immature birds still have a full head of feathers. Roseate Spoonbills feed in the saltmarshes and impoundments of our coast, slicing their flattened bills from side to side as they march along in the shallow water. When they bump against something tasty they snap their bill shut, trapping their prey in a spoon-y embrace. Roseate Spoonbills eat a diet of small fish and crustaceans, including mummichogs, blue crabs, and shrimp.

If you want to appreciate the beauty of our utensil-snouted fusia-feathered friend in person, I can recommend two hotspots on Edisto. I often see Roseate Spoonbills below the bridge along the Dawhoo River in early summer and more reliably on the back of Jason’s Lake in Botany Bay WMA in late summer. So grab your binoculars and camera and get out there!

This week for Flora and Fauna Friday, we’re looking at a common but unique wetland plant. This week were talking about Lizard’s Tail (Saururus cernuus).

Lizard’s Tail belongs to the family Saururaceae. This family only contains 7 species, of which only two are found in the United States. Of those two, Lizard’s tail is the only one found East of the Mississippi. This leaves Lizard’s Tail quite unique in appearance from anything else in our area.

Lizard’s Tail is a perennial wildflower that thrives in shaded freshwater marshes and open swamps. It’s alternate arrowhead-shaped leaves carpet the mud of many a shallow backwater and bottomland in the Lowcountry. The plants grow in dense stands and can reach about 4ft in height. In the spring the plants produce a slender spike of green-white flower buds. These flower buds open from the base of the inflorescence to the tip, creating a white bottle brush at the bottom with an off-green “lizard’s tail” of buds still hanging from the tip. In the winter the plants die back to their roots to start the cycle anew.

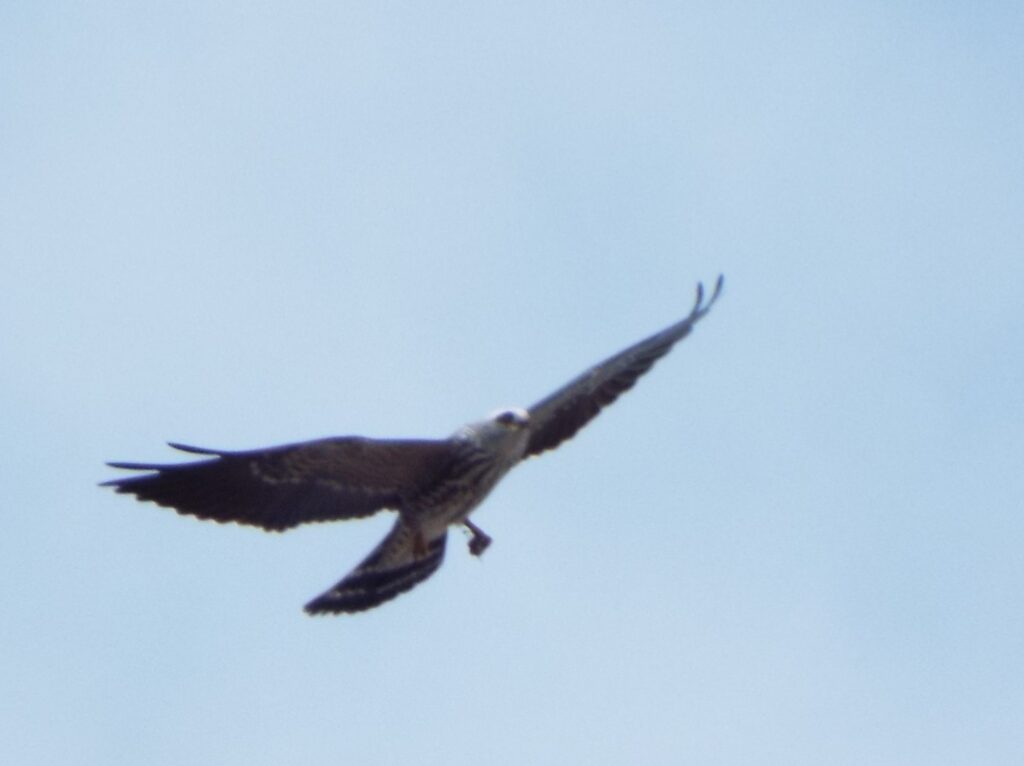

This week for Flora and Fauna Friday, were taking a look at a pair of raptors who glide into our horizon every summer. This week were talking about the Kites.

Here in on Edisto we have two species of Kite that regularly grace our skies come summer to feed and breed. They are the Mississippi Kite (Ictinia mississippiensis) and the Swallow-tailed Kite (Elanoides forficatus). Both species are similar, but not identical, in habits, habitat, diet, and behavior. Kites are highly agile and efficient fliers. They spend their days hunting on the wing. Soaring high over fields, marshes, and open wetlands or skimming just a few feet above the treetops. Rarely ever flapping their wings. Kites feed primarily on large insects, like beetles, wasps, and moths, that they catch in mid-air or on small vertebrates, like lizards, frogs, and bats, that they snatch from the treetops. Kites take their meals on the wing, eating it from their talons. Kites are rather social and can often be seen hunting in large swarms of birds over open areas. Mississippi Kites are much more social than their Swallow-tailed cousins but the latter won’t hesitate to join in on a feeding frenzy if the opportunity arises.

Both species are partial to lowland forests with intermittent open habitat, but the Swallow-tailed is definitely the more specialized of the two. Swallow-tailed Kites have a strong preference for swamps, marshes, and floodplain, riparian, and bottomland forests. Mississippi Kites are more generalist in habitat, utilizing some drier forest habitats as well as pastures, farmland, and even urban areas. Predictably, Mississippi Kites thus have a much larger range and are found throughout much of the state. Swallow-tailed Kites are almost exclusively found in the coastal plain. Both species are common here on Edisto in the summer, but the Mississippi Kite is definitely easier to find. There’s usually at least one, if not 20, circling over the fields at King’s Market. Swallow-tailed Kites are harder to pin down but the edges of lowland forests or marshes are always a good bet.

This week for Flora and Fauna Friday, the subject is a naturalized exotic plant that is, nonetheless, a staple of old Edistonian gardens and the shoulders of Highway 174. This week we’re sneaking a peek at the Dragon’s-Head Lily (Gladiolus dalenii).

Like other members of the Iris family, Gladiolus dalenii loves wet soils. On Edisto it thrives in the shady, disturbed, sandy, and wet soils of the ditches along Hwy-174 and it’s many branches. The species is perennial and spreads clonally through its roots. The large, flat, erect leaf blades give the genus their common name of “Sword Lilies”. The Dragon’s-Head Lily produces a single flower stalk per leaf clump that can reach over 5 feet in height. Each stalk bears about a dozen large flowers along one side. The flowers are a fiery blend of yellow and red-orange. Although the species is exotic, it’s quite innocuous to the native plant communities.

The Dragon’s-Head Lily is a native throughout tropical and eastern Africa with quite an expansion range on the continent. Its history and range in the United States is poorly understood, with only a few isolated reports of it in LA, MS, and AL. However, I can tell you for certain that it’s made quite the home for itself on Edisto Island. Decades in the past it was a popular ornamental planting in both Edisto and Beaufort. Part of a horticultural trend that has long since been forgotten. However, although the history of its planting, origins of the horticultural stock, and even its botanical name was forgotten by the descendants of its propagators, those same plants and the beauty of their flowers still remain. A torch that burns each spring though we know not why it was lit.