This week for Flora and Fauna Friday, it’s the original beachcomber, the Sanderling (Calidris alba).

A trip to a Lowcountry beach isn’t complete unless you spy a Sanderling. They’re by far our most common beach-going shorebird and a regular sight on any barrier island. In fact, they’re a cosmopolitan species found on shorelines throughout the globe. Sanderlings belong to the diverse “Peep” genus, Calidris, whose members are all small, compact shorebirds. Peeps can be notoriously hard to distinguish from one another. Thankfully, Sanderlings are one of the easier species to identify. Overall, they’re middle of the road in size and shape, being most similar in form factor to a Dunlin. But, unlike a Dunlin, their bill is short and unmarked. Looking closer, they have black legs, a black bill, and, in winter, a pale plumage of snow-white below and aluminum gray above. In summer, their head and wings warm to a mottled rusty-orange and ebony-black as they prepare for a long flight north to breed in the Arctic Circle. Juvenile birds stick around in South Carolina over summer and carry their winter plumage, but with a back mottled with black blotches. Another unique feature of the Sanderling, which can help with picking them out of a crowd, is that they only have three toes, lacking the fourth “spur” toe on the rear of their foot. This allows for their unique running gait.

Sanderlings feed on invertebrates that get washed ashore by the tides or that wriggle out of the dampened sand. Sprinting and zig-zagging, they drift along the seashore; dodging wave breaks as they pluck morsels from the wet sand. Often times, darting towards the receding sea to snatch up zooplankton thrown ashore before hightailing it uphill to avoid getting swamped by the surf. This behavior of mad dashing down the beach, pencil thin legs ablur punctuated by whiplash inducing snack breaks, makes this little white shorebird one of our easiest to spot, and most endearing to watch, when our paths cross where land ends.

This week for Flora and Fauna Friday it’s the towering flower of the coastline, Seashore Mallow (Kosteletzkya pentacarpos).

Seashore Mallow (AKA Saltmarsh Mallow) is found throughout the coastal zone of South Carolina as well as all the East and Gulf Coast states. It grows in brackish marshes, ditches, and the upper reaches of other sunny and tidally influenced wetland systems. Seashore Mallow grows to head height as an herbaceous, perennial bush. These Mallows also clump together to create small thickets. They have large triangular-ish leaves and that “Christmas-Tree” growth form that most Mallows tend to have, with a tall and straight central stem and diagonal limbs branching off below it. And again, like most Mallows, it has large and beautiful flower. The flower of Seashore Mallow is two to three inches across with five pastel-pink petals arranged around a central golden style, like a miniature parasol. These flowers attract many bees and butterflies to pollinate them, and even a hummingbird or two. Seashore Mallow is one of very few showy native wildflowers that can tolerate regular saltwater intrusion, making it a great addition to waterfront yards and coastal ponds that see a bit of salt.

Seashore Mallow is typically found in the upper reaches of tidal rivers, creeks, marshes, and ditches. It’s usually growing right there in the brackish transition zone. This is a consequence of its adaptations for tidal dispersal. The large seeds of Seashore Mallow contain air pockets that make them buoyant. This permits them to float downstream after heavy rains and then ride high tides, particularly our king tides, inland to a new home. However, Seashore Mallow isn’t the most salt tolerant plant. So it can’t survive in the true salt marsh or areas with regular full-strength tidal influence. So it relies on exceptional tides to carry it far and deep upstream into the coves and crevices of the interstice we call the brackish zone.

This week for Flora and Fauna Friday, we have a beetle like none other, the Palmetto Weevil (Rhynchophorus cruentatus).

The Palmetto Weevil is a hard one to misidentify. Their inch-long, pill-shaped body is colored a base coat of asphalt-black and accented with variable blotches of cinnabar-red. Palmettos Weevils are our largest Weevil species in North America. Like most Weevils (family Curculionidae) Palmetto Weevils possess an elongated rostrum, or snout, with their antennae emerging from the side of it. At the end of this rostrum is their mouth. Males have a bumpy rostrum and females a smooth one. You might now be wondering, “Why the long face?” Well, it allows Weevils to bore down into vegetation more efficiently than other beetles. For example, this allows them to feed on the inside of a nut by just punching one little hole, rather than having to fit their whole head inside. More importantly, it allows female Weevils to turn around and easily lay their eggs deep in a fruit, nut, or the tissue of a plant, rather than in a shallow cut at the surface like most beetles must. This often circumvents some of the plant’s defenses and gives their offspring a head start.

The Palmetto Weevil is found throughout Florida with a range spanning up the East Coast to South Carolina. As their name implies, they host on palmettos. So their range is ultimately limited by the abundance of host palms. Their primary native host is the Cabbage Palmetto but they will use Saw Palmetto as well. Yet, they will also make use of many of the exotic and ornamental palms when available. Female Palmetto Weevils lay their eggs at the base of live palm fronds. Once hatched, their larvae burrow into the trunk of the Palmetto and feed around the bud at the crown of the palm, growing as they go. Once full grown, they build a cocoon to pupate. All told, it takes about three months for a Palmetto Weevil to go from egg to adult beetle. The adults can live for weeks or months after. The peak time to see Palmetto Weevils is late spring, in April or May, but they continue to fly well into summer.

Palmetto Weevils are not a threat to our palmettos in a natural setting, as a whole. However, they can be destructive of individual trees when conditions are right. Palmetto Weevils, like many beetles, have an incredibly sensitive sense of smell tuned to the specific chemicals emitted by their host plant when it’s in a certain condition. For Palmetto Weevils, they can smell a stressed out or dying palmetto. Male Palmetto Weevils often survey through stands of palmettos to detect a promising palm. If they like the scent, they perch and begin releasing pheromones. Other Palmetto Weevils detect these pheromones and follow them in to join the party. The Weevils will turn this into a colony tree. As their larvae feed, they stress the tree further and draw in even more Weevils. This creates a snowball effect, which is not good for the unlucky palmetto. A Palmetto Weevil infestation can weaken or even girdle a palmetto trunk and subsequently cause its trunk to snap below the crown, killing the tree. Despite the coordinated siege-like character of this “colony tree” behavior, it is better as a whole for the Weevils and the palmettos. The colony tree is sacrificed, concentrating the Weevils there. Yet, the other healthy palmettos are spared. This keeps the two species’ populations stable and healthy, avoiding large population swings and crashes. Thus the Palmetto Weevil plays a small but nuanced role in our Sea Island ecology.

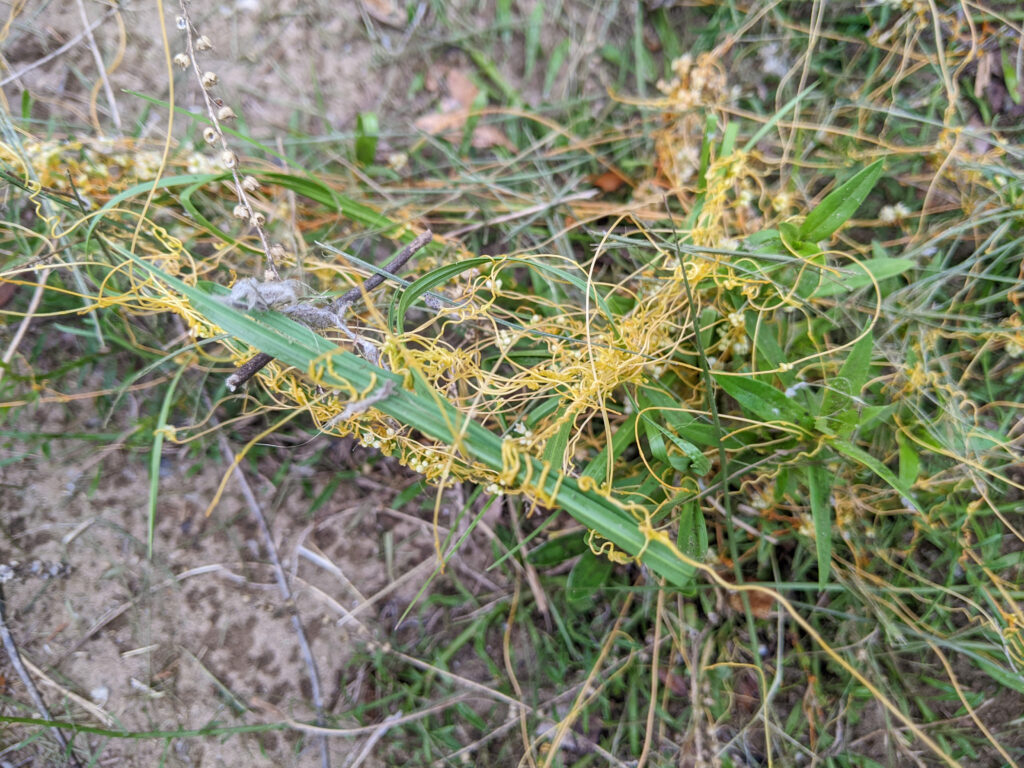

This week for Flora and Fauna Friday it’s a smothering covering of parasitic vines, the Dodders of genus Cuscuta.

Here in South Carolina we have about seven species of Dodder. Of those, four are fairly common in the Lowcountry: Field Dodder (C. campestris), Compact Dodder (C. compacta), Scaldweed (C. gronovii), and Five-angled Dodder (C. pentagona). Each has its own preferred habitats, a typical size range, and can be distinguished from one another by their flower shape and bloom times.

Five-angled Dodder (C. pentagona) is likely the most generalist of our four species. It grows up to a moderate size with moderate aggression. Its white flowers have distinctly pointed petals with inflexed, S-hooked tips. Its peak bloom time is July but can start as early as May and run into September.

Field Dodder (C. campestris) is found in fields, lawns, and other regularly disturbed sites. It’s most similar to Five-angled Dodder but a bit more aggressive and lacking pointy flower petals. Its flowering peak is August, but may begin in May and carry into September.

Sessile Dodder (C. compacta) is a forest specialist, with a compact form adapted to shadier, low energy environs and a greater ability to tap into woody plant twigs. It has smaller, narrower, ivory-white flowers often packed together in dense clusters along a host’s stem. It blooms in late summer, peaking in September.

Scaldweed (C. gronovii) is the largest and most aggressive of our four species. It prefers riparian areas, ditches, and wetland margins. It has larger, pearl-white flowers with rounded petals that emerge at Autumn’s dawn in mid-September.

Apart from subtle differences in life history and flower shape, all our Dodders look remarkably similar. As members of the Morning-Glory family, Convolvulaceae, they grow as thread-like vines, twisting and twining between the stems and twigs of neighboring vegetation. Yet, unlike normal Morning-Glories, Dodders grow no leaves and set no roots, at least no roots in the traditional sense. Dodders are a parasitic plant and subsist wholly through leeching the lifeblood from their hosts. When a Dodder seed germinates, its lone goal is to find a suitable host to latch onto. Dodders typically parasitize herbaceous plants but can tap into the new growth of woody shrubs and saplings. Dodders target stems and twigs, twisting tightly around them. This coiled vine swells and produces adventitious roots that burrow into the vascular tissue of their host. This parasitic root structure is called a “haustorium”, the graft of an involuntary scion. The nutrition sapped from the host sustains and grows the Dodder into a straw-colored net that swallows hedges and thickets in a tan, tangled blanket; a golden fleece that withers and smothers life from the Earth, rather than nurturing and invigorating it like its mythical analog. The vines of Dodders are thin, wiry, and a rich golden-yellow color. They crisscross and climb, entwining everything in their reach to parasitize dozens of host plants at once.

Dodders are generally found in sunny open areas, as the more prolific and better off their host plants are, the better a Dodder can persist as a parasite. This can make Dodders into crop pests when they make their way into agricultural fields, swallowing and sucking dry crops as it spreads. Dodders primarily bloom in summer and into early fall, precise timing varying with the species. Flowers emerge in clusters from the Dodder’s stems, generally at the haustoria. These flowers are small, five-petalled, and white to cream-colored with an urn-like shape. These insect pollinated flowers mature into capsules packed full of tiny round seeds, like grains of sand. Dodders, having no roots and a parasite of forbs, are themselves annual plants. But, perplexingly, Dodders have no obvious means of dispersing their seeds. These seeds attract no birds, cling to no mammals, and catch no wind. They simply fall to the ground. In our modern day they primarily get spread around by tractor, plow, or mower, falling into a crevice only to be shook loose or washed out elsewhere. Yet, their natural vector of dispersal is still mainly a mystery.

This week for Flora and Fauna Friday, we have an odd duck making its way up from down south, the Black-bellied Whistling Duck (Dendrocygna autumnalis).

Black-bellied Whistling Ducks are peculiar creatures. Somewhere between a duck and a goose in appearance and similar in behavior in many respects to a Wood Duck, they’re just plumb an odd duck. As they say, if it looks like a duck, swims like a duck, and quacks like a duck, it’s probably a duck. Well this duck looks funny and can’t quack. So you be the judge. Long pink legs, a stout pink and orange bill, a beady black eye set in a heavy white eye-ring, khaki head, brown crown, chestnut-brown chest and back, white wing coverts, and a trademark black belly make them a unmistakable bird both on the wing, on the ground, or in the trees. Black-bellied whistling Ducks love to perch on trees or stumps. Their genus name “Dendrocygna” literally means “tree swan”. It’s not a bad name given they’re cavity nesters. Much like a Wood Duck, Black-bellied Whistling Ducks nest in old Pileated Woodpecker cavities carved in trees overhanging the water. They can lay up to twenty eggs. The day after their ducklings hatch, they leap straight out the nest and freefall to the water! Black-bellied Whistling Ducks are also at home on dry ground and can readily be seen perched along pond banks, standing tall with a straight posture on long legs, or foraging for grass and grains through lawns and fields like a goose. Even still, they spend a good deal of their time in the water, feeding on vegetation and avoiding predators. So these ducks are quite adaptable! The call of the Black-bellied Whistling Duck is a wheezing whistle, sounding somewhere between a Wood Duck’s cooing and a shorebird’s mutterings.

Here in the Lowcountry, Black-bellied Whistling Ducks can be found in shallow ponds or in freshwater and brackish impoundments along the coast, especially within the ACE Basin. However, it wasn’t always like this. Over much of the last century, the Fulvous Whistling Duck (D. bicolor) was an irregular visitor to the Lowcountry. Then, in the 1990s, the Fulvous Whistling Ducks stopped coming and, about the same time, the Black-bellied Whistling Ducks start appearing. In just the last decade, their numbers in South Carolina have increased by an order of magnitude. Historically, the Black-bellied Whistling Duck has been limited to the American tropics and South Texas. In about the 1970s, a critical mass of Black-bellied Whistling Ducks strayed into the Florida peninsula. At which point they established a permanent breeding population. From those few pioneers, they multiplied and spread outward and upward to occupy much of Florida. Some enterprising young ducks eventually made their way north along the Atlantic and found the well-kept duck fields of the sub-tropical ACE Basin festooned with vacant, low-rent Wood Duck boxes. You could liken it to the Promised Land for this peculiar duck. In just the last ten years they’ve established a breeding population in the ACE Basin, particularly on Edisto Island. I’ve seen more and more of their ducklings with each passing year and pairs appearing on the banks of most all our small ponds.

This week for Flora and Fauna Friday, we have a western wildflower with a love of wastelands, Bitter Sneezeweed (Helenium amarum).

Bitter Sneezeweed is a small wildflower, usually only reaching a foot or so in height with an upward, bouquet-like shape. Its leaves are thin, wiry, and numerous. They lend the plant a hazy, almost blurry look from a distance, where its leaves are too fine for the eye to individually resolve, like a mirage shimmering above a desert. Bitter Sneezeweed gets its common names from its foliage. Its leaves are chock full of bitter chemicals to discourage herbivores from chowing down. Yet, dairy cattle will eat it incidentally or when pickings are slim. Then those bitter compounds will transfer to that cow’s or goat’s milk, making it unpalatable for people. The generic Sneezeweed name comes from an old practice of drying and crushing the leaves of related Common Sneezeweed (H. autumnale) to make a powder that induced sneezing when inhaled. Above those leaves and atop this minute, multi-stemmed bush appears its handsome flowers, golden spheres served upon a dish of lemon-yellow rays. Bitter Sneezeweed begins to bloom about the summer solstice and carries forward through the end of summer. Its blooms are often the only flash of color, and one of a scant few sources of pollen and nectar, in many locales during the dog days of a Lowcountry summer.

Here in South Carolina, we have about a half dozen species of Sneezeweed, with Bitter Sneezeweed being the most widespread by far. However, Bitter Sneezeweed is a native to eastern Texas and its neighboring states but, thanks to us, has spread to new habitats throughout the South, to include all of South Carolina. Bitter Sneezeweed is adapted to the sedimentary soils of East Texas and is especially tolerant of the acidic, droughty, and calcium heavy soils found there. Across the South, it has settled into a second home on the disturbed and barren soils mankind leaves in the wake of our infrastructure. Bitter Sneezeweed is most often found along dirt roads, causeways, dirt pits, gravel parking lots, abandoned buildings, and others such sites on the fringes on man’s influence. These areas often have poor, compacted, weathered, droughty soils that are high in calcium from surrounding concrete, limestone, or oyster shells. Sprinkle on a little bit of shade from the midday sun, cast by a tree line or building, and this is the humble niche Bitter Sneezeweed has nestled into across the South.

Bitter Sneezeweed is a notable example of a plant where the line between native and non-native is blurred. It is native to the Southern United States, but certainly not to South Carolina. Here in the Lowcountry I could hardly call it an invasive species. (Although I’m sure there are some dairy farmers elsewhere in the Southeast who have a justifiably opposing perspective.) If anything, Bitter Sneezeweed in the SC Lowcountry is often a passive member of, or even a positive addition to, the barren, unnatural landscapes it inhabits, rather than an existential threat to their reclamation. It’s a secondary symptom manifest of a larger issue, rather than the source of poor health itself. I view Bitter Sneezeweed, and similar Gulf Coast advents, as honorary native plants here in South Carolina. These are beneficial plants that can augment and enhance our impaired landscapes by occupying the unfilled artificial niches we humans accidentally create. Thus they’re filling an open niche and simultaneously excluding exotic invasives species, who could have established there instead and threatened biodiversity in the surrounding landscape.

This week for Flora and Fauna Friday we have a two-stage, bi-colored insect that’s doubly easy to recognize, the Giant Leopard Moth (Hypercompe scribonia).

The Giant Leopard Moth is a fairly large moth in the Tiger Moth tribe, Arctiini. This moth is about two-inches long and mainly monochromatic in pattern. Their wings are pearl-white and spotted with rings and blotches of matte black. Yet, beneath those wings hides an abdomen of pastel-orange and iridescent-sapphire. A hard to miss and elegantly beautiful moth if ever there was one! What’s equally hard to miss is their caterpillar. The larval stage of the Giant Leopard Moth is what is colloquially known as a “wooly-bear” caterpillar. Their caterpillars get this name from being cloaked in a pincushion pelage of stiff hairs, giving them a thick and fuzzy appearance, like a bear’s winter coat. We have several species of Tiger Moth whose caterpillars go by the Woolly-bear nickname but the Giant Leopard Moth larvae’s are particularly recognizable. When fully grown, their larvae are a deep, semigloss-black with burgundy tones below and flashes of ruby-red in the joint between each body segment. In their younger instars, they have a banded two-tone appearance of black and cayenne-red. These caterpillars reach nearly three-inches in length in their final instar!

The Giant Leopard Moth’s caterpillar feeds on a wide variety of plants and the species is a common sight for gardeners throughout the Lowcountry. They’re often found scurrying around in backyards or cozied up in a silken hammock beneath yard debris, palmetto fronds, brick piles, forgotten pots, and wayward lumber. Unlike some of our other fuzzy caterpillars, these Woolly-bears are safe to handle and can’t sting. Their only defense is rolling into a difficult to swallow ball when bothered. Giant Leopard Moths overwinter as caterpillars, pupate in late spring, and the nocturnal adults emerge and fly throughout the summer.

This week for Flora and Fauna Friday, we’ve got a genus of wet-footed wetland shrubs, our Willows (Salix spp.).

Here in South Carolina we have four native species of Willow: Black Willow (S. nigra), Carolina Willow (S. caroliniana), Prairie Willow (S. humilis), and Silky Willow (S. sericea). Of those, Black Willow can be found statewide and Carolina Willow lives throughout the coastal plain. Prairie Willow is adapted to fire and found sporadically here in Longleaf Pine savanna ecosystems. Silky Willow is found in the Blue Ridge Mountains and its foothills. You’ll also see the ornamental Weeping Willow (S. babylonica), an exotic from China, planted around the State. For today, I’ll be focusing on Black Willow and Carolina Willow.

These two common Willow species share a variety of characteristics. Both grow on wet soils, all the way from damp to standing water. Both prefer full sun but can tolerate some shade. In growth form, they tend to be multi-stemmed shrubs, spreading outward into a spherical shape from ground to crown. These two species have leaves that are simple, finger sized and shaped, but with a long pointy tip. Both bloom in April to May with short spikes of goldish-green flowers. These mature into white tufts of windborne seeds which are blown far and wide with the aim to nestle along a damp pond bank. Willows also spread by their roots and through stem layering. They have pliable but fragile limbs, which break and propagate readily from cuttings, an adaptation for life on river banks where violent floods can rip a Willow apart and cast it downstream. Its weak wood allows the limbs to break away, protecting the roots and allowing the Willow to re-sprout. Simultaneously, the broken branches can root anew on a sandbar or logjam downstream.

Black Willow is a highly adaptable species, growing in a plethora of soil types and into a myriad of shapes. Most commonly, it’s found growing along pond edges, stream banks, and in shallow, sunny wetlands. Normally it grows as a hedge of expanded shrubs but, in stable conditions, will grow up into a reasonably sized tree.

Carolina Willow is very similar in appearance to Black Willow but needs wetter soils to thrive. It also doesn’t really grow into a tree, staying as a large hedge or shrub. It’s found in similar wetland margin habitats but has more salt tolerance, and so is often found closer to the coast and in old tidal impoundments. The quickest way to tell these two species apart is by their leaves. Black Willow leaves look about the same on the top and bottom. Conversely, Carolina Willows have silvery-white undersides to their leaves.

Willows have a lot of wildlife associations and provide ecosystem services. Their flowers are dual-pollinated, spreading pollen on the wind but also working with pollinators, specifically bees, trading pollen for transport. Willows are also the caterpillar host plant for three of our large, showy butterflies: the Eastern Tiger Swallowtail, the Viceroy, and the Red-Spotted Purple. The ecosystem services Willows provide make them a valuable asset in wetland systems. As a supple, spreading shrub that grows on wetland margins, Willows provide three key benefits to wetland ecosystems. They stabilize banks with their roots, they slow water and trap sediment in their labyrinth of stems, and they provide both shade to fish and structure to aquatic animals living beneath them. One final fun fact, the living tissue of Willows contains Salicylic Acid, which is used widely in indigenous medicines as a pain reliever and was isolated in the early 1800s to create the drug Aspirin.

This year for Pollinator Week (6/17 – 6/23) we’re doing a 7-part series about native pollinators on Edisto Island!

We, as a civilization, need pollinators. They keep the gears of agricultural and ecosystem services turning behind the scenes, rendering an invaluable service to plants, which yield these values to us. Pollinators need our help. Thankfully, pollinators are everywhere and anyone can lend them a helping wherever they are.

Pollinators are a diverse group of animals adapted to a wide range on ecosystems, habitats, and environmental conditions. They’re able to fend for themselves and don’t need any special treatment as a whole. However, they are all being hit from every angle with overwhelming forces they can’t overcome on their own. The biggest threats to pollinators right now are misuse of insecticides and habitat loss. As an individual, these threats are easy to dissipate at the small scale. Don’t fog for mosquitos, don’t spray insecticides in your garden, leave leaf litter around the edge of your yard, create a brush pile, leave dead flower stems alone, don’t mow as often, and plant native plants where ever you can.

However, the biggest contributor to both these threats in the Lowcountry is suburban sprawl. The best way to curb sprawl is by supporting local land conservation efforts. Land conservation is what we do here at EIOLT. We protect dirt from destruction. We save special places for tomorrow. We humans rely on natural ecosystems and agricultural crops for food and natural resources. Food crops and natural ecosystems need pollinators. Pollinators need native plants. Native plants need soil. Soil is the land. In order to protect our native pollinators and safeguard our futures, we need to first protect the land that we all rely on. Protect places for plants, for pollinators, for people, for the future, forever. The work of the Edisto Island Open Land Trust protects the capacity of land to support pollinator habitat, our native plants, our wildlife, our natural resource economy, and the intrinsic beauty of Edisto Island. We need your help to conserve land, and everything that relies upon it. If you’re not a member already, please considering joining EIOLT and, if you are, thank you, sincerely, for all that do to protect the one-of-a-kind Edisto Island.

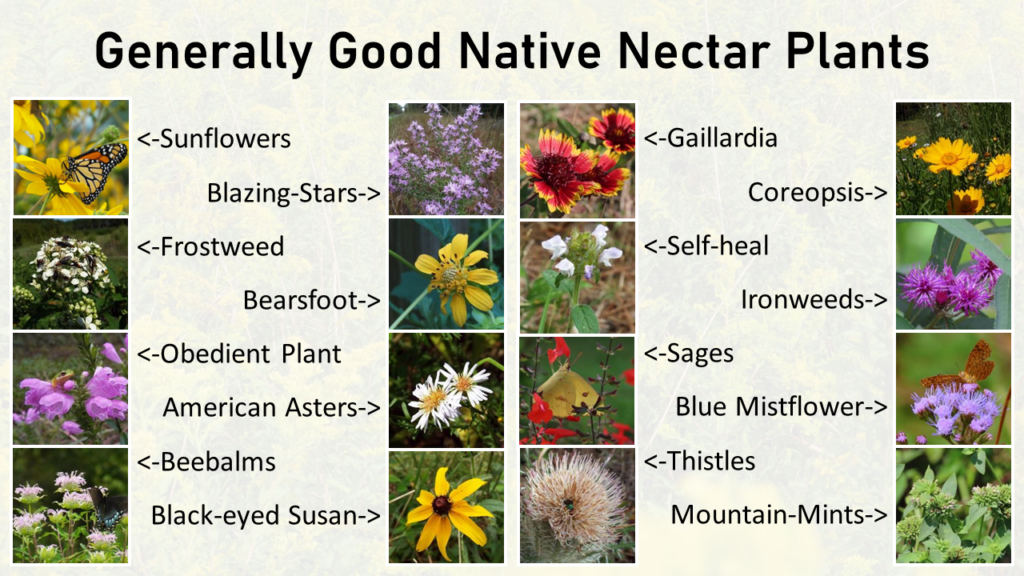

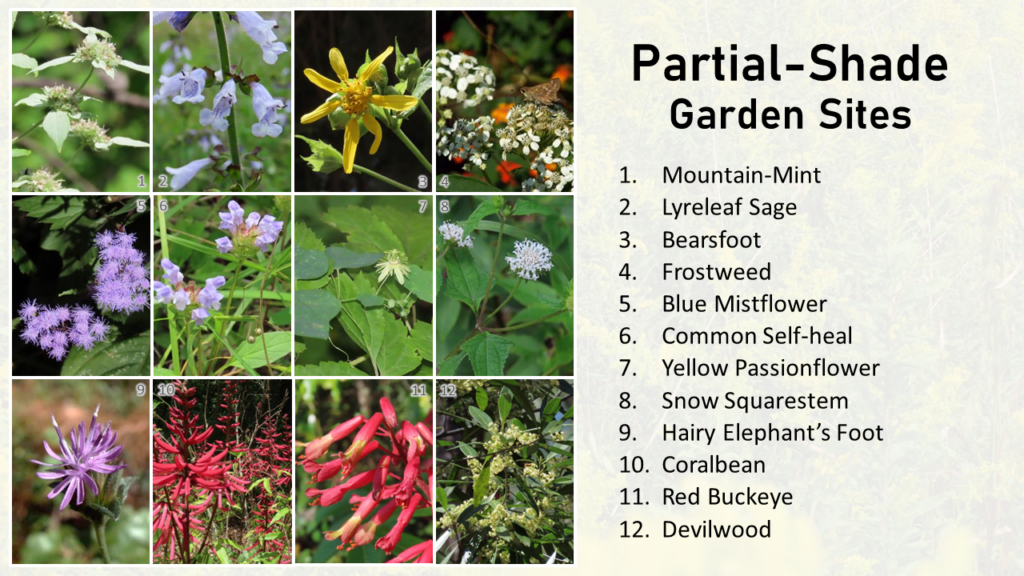

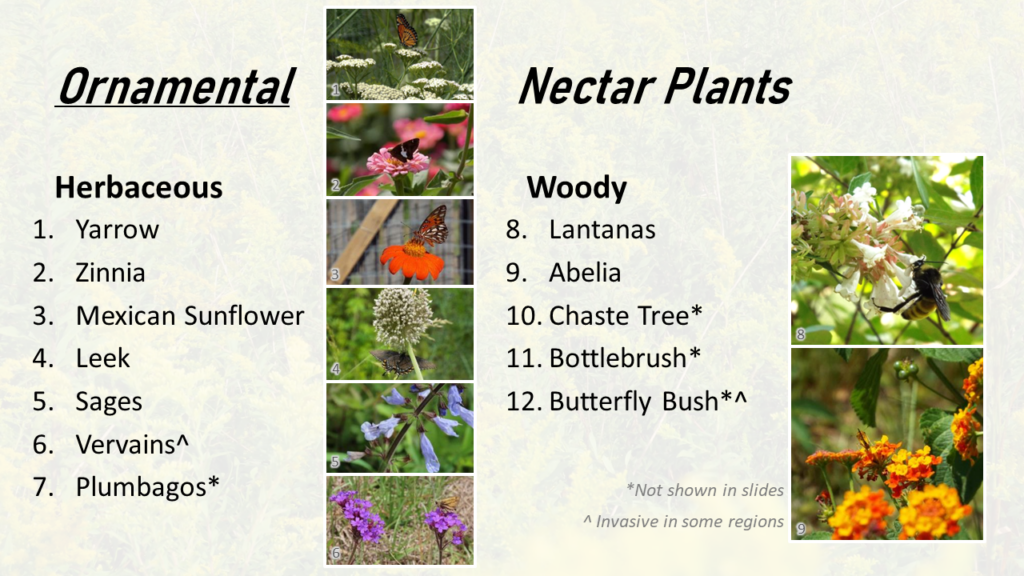

Pollinator Week 2024: Pollinator Plant Recommendations for Edisto Island

This year for Pollinator Week (6/17 – 6/23) we’re doing a 7-part series about native pollinators on Edisto Island!

If you’re considering building a pollinator garden, bringing native plants into your yard, or managing land for pollinator habitat, you’re going to need to know which plants work best for Edisto Island. Here, we’re in the borderline subtropics of the Lowcountry, meaning many plant recommendations you’ll find online for the Southeast US often aren’t worth much of anything. However, lucky for you, I’ve spent the better part of the last decade planning, planting, and managing native plant gardens in the Edisto area. So, I’ve got a good handle on what works and what doesn’t here and I know the plants that are specialized to our unique sea island soils and climate. I also spent all of this spring building out a set of slides and a pollinator garden plant recommendation list focused on Edisto Island.

If you’d like to give them a gander, check out the link below:

These plant recommendations of mine are specifically focused on butterflies (because, as a butterfly researcher, I’m biased) but almost all are good for a wide range of our native pollinators. One thing I do want to stress is the importance of using native plants in your pollinator garden, yard, and lawn. Native pollinators are adapted to make use of native plants. Native plants are adapted to our local climate, soils, and wildlife. Native plants, pound for pound, will always be better for our native pollinators and wildlife than any exotic ornamental plant. Further, many ornamental plants, even the ornamental varieties of native plants, have been bred in such a way that they no longer provide all the benefits they should to pollinators. So, plant native and, if you can, plant local ecotypes of native plants. These plants will grow better, require less care, and provide the maximum benefit to our native pollinators and wildlife.

For further information, recommendations, and sources of native plants and seeds, you can also check out the SC Native Plant Society and Xerces Society, both linked below:

https://xerces.org/pollinator-conservation/native-plant-nursery-and-seed-directory