There is nothing like history when it comes alive. Too often tossed aside in unread books, or overlooked in cavernous museums, our shared history is needed more than ever as we collectively work to build a more inclusive, compassionate, and tolerant community. The c.1885 Hutchinson House, is one of the oldest surviving houses built by African Americans during the Reconstruction Era on Edisto Island.

Henry began building the home on Point of Pines Road after his marriage to Rosa Swinton. To get the full picture of the home’s significance, we need to start with the life of Henry’s father, James “Jim” Hutchinson.

Jim Hutchinson was born enslaved c.1836 on Peter’s Point Plantation, the son of an enslaved woman named Maria and her enslaver, Isaac Jenkins Mikell. In his twenties, Jim and his first wife, Nancy, were beginning their family and had two sons, Lewis & Henry just as the American Civil War was brewing. South Carolina seceded from the Union on December 20th 1860. A few months later, on April 12th 1861, Fort Moultrie fired upon Fort Sumter, beginning the American Civil War. In the fall of 1861, Port Royal, just south of Edisto, was captured by the Union Navy and the Confederacy ordered the evacuation of all Whites on Edisto Island. Many plantation owners took their enslaved individuals with them but few, if any, evacuated with all. This left many previously enslaved, Jim and his family included, abandoned. The Union Navy soon came and occupied the coast, now referring to formerly enslaved people as “contrabands.” In 1863, ten planters’ sons volunteered for a scouting mission to Edisto Island. They left Adam’s Run and crossed over at Jehossee to set up camp at Tom Seabrook Plantation on Milton Creek. There they monitored the movements of the Union Navy and reported back to the mainland. Their presence was soon known to Jim Hutchinson and his companions and in April of 1863, they hailed the Kingfisher, a Union patrol boat, and informed the crew of the location of the Confederate Scouts. Soon, the Union Navy surrounded and captured nine of the ten scouts including Townsend Mikell, the son of Jim’s former enslaver, and his half-brother. The following winter, Jim joined the Union Navy and served aboard the Kingfisher before being transferred to the Vermont and then the McDonough. He was discharged in April of 1865 and returned home to Edisto Island a free man and a Civil War hero to many.

Near the end of the Civil War, General Sherman’s Special Field Order 15 confiscated the coastline from Charleston, South Carolina to the St. John’s River in Florida. The plan was to give the land to newly freed Black people. The Freedmen’s Bureau began issuing land certificates on Edisto in July of 1865. By October, 369 land certificates were issued to freedmen on Edisto, giving each 40 acres of land. The land grants were short lived, however, after the assassination of President Lincoln. On October 19th, President Andrew Johnson canceled General Sherman’s order, returning the land to its previous owners.

As a result, James Hutchinson and other African Americans organized clubs to pool their money, purchase former plantation lands, and subdivide them into farms. By 1880, Black Edistonians owned more than 4,000 acres of land in farms ranging from 10 to 60 acres in size.

Freedmen were looking for economic empowerment for themselves and their families, as well as the ability own their own land. Jim Hutchinson began fighting for the freedmen of the Sea Islands. Jim engaged in political activism in his community, ran for election in local politics, partnered in the creation of a black-owned ferry company, and organized land purchase cooperatives among freedmen. All to get titles to land in the hands of the people that needed it and establish Black land ownership.

In 1870, Jim chaired the committee that sent a letter to the Governor petitioning for the purchase of a plantation to divide among the freedmen of Edisto. In 1872, he organized a land purchase cooperative for him and twelve other freedmen to purchase 234 acres of Seaside Plantation. In a land purchase co-op, each member pays a share of the purchase price and receives a proportional amount of land in return. This allows buyers with limited funds to work together to purchase large tracts of land to subdivide amongst themselves. Jim purchased approximately 30 acres of Seaside Plantation and moved his family there. He planted the land to make a living. In 1874, Jim was appointed the Trial Judge for Edisto Island for a short period. In 1874, Jim entered into a partnership with several other investors to start the Toglio Ferry Company. Given that there were no bridges on or off Edisto Island at the time, having a Black-owned ferry company was a great boon to the freedmen community. They could now rest easier knowing that they would receive fair treatment and prices from the ferry when shipping crops to market or heading into town for business. In 1875, Jim organized a second land co-op with 21 other freedmen and was successful in purchasing 404 acres of the Clark’s Shell House Plantation. From this co-op, Jim received 74 acres of high ground and 90 acres of marsh, including the old Clark Manor and all its outbuildings. In 1878 and 1880, Jim was elected as a delegate to the Charleston County Republican Party Convention and, in 1882 and 1884, he was elected as Precinct Chairman for Edisto Island in the Convention.

On July 4th 1885, Jim Hutchinson was murdered at the home of his son Lewis, by a man named Frederick Barth from Wadmalaw. There are several articles published in the News and Courier about the incident, describing the circumstances that led up to the shooting by Mr. Barth and his conviction for murder. Barth appealed his sentence one year later and was acquitted by an all-white jury.

Jim was a man full of conviction, fiery passion, and persistence. He did much to better the lives of his friends, family, and neighbors on Edisto Island and he fought for what he felt was right and just. He put his whole effort into his goals to secure land and voting rights for African Americans. Born into enslavement, Jim rebelled against his situation, fought for his freedom during the American Civil War, was a skilled sailor, and eventually became a respected investor, broker, politician, and community leader.

Henry was born enslaved in 1860 on Peter’s Point Plantation to Jim and Nancy Hutchinson. Little is known about Henry’s early years, but we can surmise growing up on an isolated island in a war-torn country wrought with political turmoil and economic depression was difficult. By the time he was twelve years old, his father, Jim Hutchinson, had purchased 30 acres at Seaside Plantation and Henry moved there with his family. By 1879, nineteen-year-old Henry, had become a farmer and was working 10 acres of his father’s land. In 1885, Henry Hutchinson happily married Rosa Swinton (from Georgia) and built their family home, but sadly would soon mourn the loss of his father, James “Jim” Hutchinson, who was murdered on The Fourth of July.

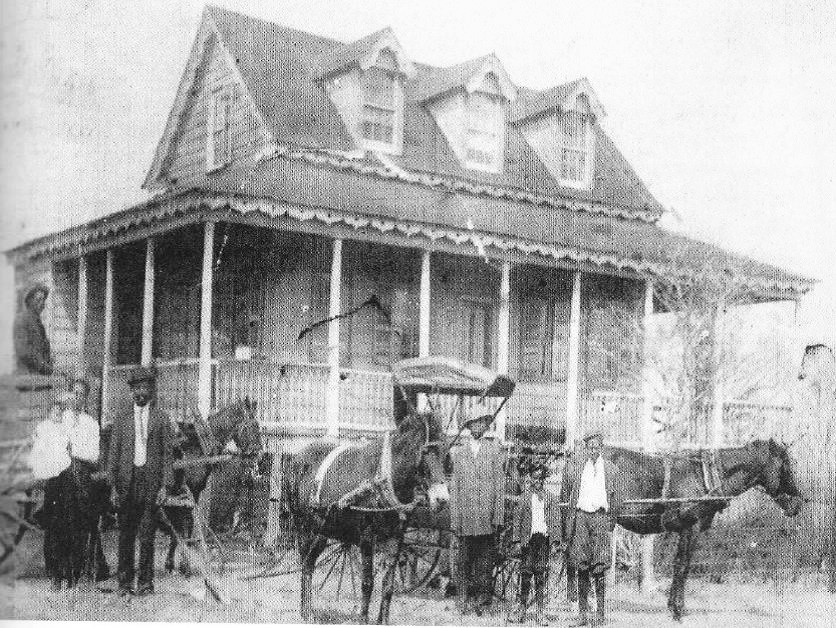

Henry and Rosa’s home, The Hutchinson House, is a rectangular, two story residence featuring side gable roofs and eaves decorated with stylish Victorian bargeboard details. The weatherboard clad house rests on a raised brick pier foundation with a long, divided rear room on the back of the house. The house sits atop a shallow ridge of land overlooking marshland and surely commanded attention from the start. Part of the Clark Community, a Black Settlement Community started by his father, the Hutchinson House faced Point of Pines Road and took advantage of the well, stable, barn, and cotton house from the old Shell House Plantation. Henry and Rosa had eight children and took in many more children. Henry raised livestock, grew subsistence crops, and planted Sea Island Cotton on most of his land.

Henry made the bulk of his living from Sea Island Cotton. Freedmen typically grew vegetables and raised livestock for their families but they also planted whatever spare land they had in Sea Island Cotton. Sea Island Cotton was a cash crop that stored well and grew strongly on the Sea Islands. It was reliably sold for cash, which was necessary to purchase supplies that could not be easily made or grown on the farm. Cash was needed for things like sugar, tools, lumber, and clothing. Henry eventually set to refurbishing the old cotton house and purchased his own steam-powered cotton gin. After the turn of the century, his gin was up and running and he was processing and shipping cotton to market for his neighbors. Henry acted as an intermediary between his neighbors and his factor, Dill, Ball, & Company. A factor is like a sponsor for a farmer. They loaned the farmer funds to purchase cottonseed, fertilizer, and supplies and the farmer pays them back at the end of the year in bales of cotton. Henry essentially ran a farming co-op. Black farmers brought their cotton to Henry for processing and packing, Henry shipped that cotton with his own to the factor, the factor sold the cotton, took their payment, and returned the profit. Henry distributed the proceeds to the farmers. The farmers then returned the following spring to report what supplies they needed to plant that year, Henry took out a loan for the group, purchased supplies, and then distributed them. By doing this, Henry gave neighboring small farmers, and himself, access to the crop liens and better prices that factors offered.

The arrival of the Boll Weevil decimated the Sea Island Cotton Crop and eventually collapsed the market. Henry continued to farm the rest of his life and passed away in 1941 at the age of 80. Rosa passed away in 1949 at the age of 83.

Lula was born in 1887, the oldest daughter of Henry and Rosa Hutchinson. She pursued a career in teaching and received her teaching certificate from the Avery Institute in 1905. She met her husband, William Whaley, Jr., shortly thereafter on the job. Lula began teaching at the Larimer Colored School the day its doors first opened in 1906. She also taught at the Central Colored School. She was living with her parents, Henry and Rosa, in the Hutchinson House in the 1940s. After her parents passed, she continued living in the house. Lula retired from teaching in 1958 after a 52 year career. Lula is thought to have planted the pecan and fruit trees around the property and started the flower gardens in front of the house. Lula passed away in 1974 at the age of 87.

The land where the Hutchinson House sits is just as significant as the home itself. It is land steeped in history dating back to the Oristo Indians and continuing through the first settlers of Edisto Island, Plantation Aristocracy, Reconstruction, Jim Crowe, the Great Depression, into modern day. The full history of Edisto Island is displayed through this one family’s farm.

The property is located along the only high ground route from the interior of Edisto Island to the Native American shell rings of Fig Island along the North Edisto. The Oristo tribe wintered on Edisto, harvesting her bountiful oysters and seafood and manufacturing pottery until spring. Over the years the shells of the oysters they ate and the shards of pottery that failed the kiln were piled high in rings along the marsh. Millennia old archaeological treasure troves that exist to this day. It is no stretch to think the Oristo trekked for many years through the land that would come to belong to the Hutchinsons.

When English colonists first settlers Edisto Island, they divided the land through grants. The first grant on Edisto Island, to Paul Grimball in 1683, included the land where the Hutchinson House sits. Being on the far end of the 1,500 acre land grant, this land was likely the last to be cleared and scarcely worked until after the Revolutionary War, when Sea Island Cotton made its debut.

Sea Island Cotton became widely planted on the Sea Islands of South Carolina starting around 1790. It filled the need for an upland cash crop in the wake of the Indigo markets collapse. With it came an insatiable demand for its long, silken lint and a growing hunger to plant it as far and wide as possible, no matter the cost in human suffering. Around Sea Island Cotton was built the Plantation aristocracy that swallowed Edisto Island whole. Africans were enslaved and shipped into the North Edisto by the thousands annually to fuel the cultivation of both Cotton and Rice. Untold pain and grief was endured by the enslaved in the antebellum. During this period, this property was subdivided and eventually married out of the Grimball name and into the Clark name. It belonged to a plantation known as Shell House or Clark Plantation. The Clark Manor stood next door to the Hutchinson House, just a few hundred feet to the west. It contained several outbuildings, including a cotton gin house and nine slave cabins.

In 1860 the Civil War began. Port Royal fell quickly and the Union Navy was poised to take Edisto. All white Edistonians evacuated Edisto Island in fear of being captured. For a short time, slaves on Edisto were without masters and governed the Island as they saw fit. Clark Manor was occupied throughout this time by former slaves and its lands worked to feed their families. However, soon the Union Navy came to occupy the Island. A number of Edisto men joined the Navy to fight and many families were relocated to Port Royal.

With the end of the War and the Confederate’s defeat, the formerly enslaved were granted their freedom and white Edistonians returned to their plantations. With shocking speed the land grants freedmen held and the authority the Freedman’s Bureau possessed began to evaporate. Plantation owners reclaimed their lands and freedmen were forced to sign labor contracts or be evicted and risk starving. Seeing the need for action, freedmen on the Island moved politically to seek aid from the federal government to secure land for Freedmen, a movement led by community leaders like Jim Hutchinson and John Thorne. Sadly, their plights fell mostly on deaf ears. Unable to be deterred, Jim Hutchinson and John Thorne took matters into their own hands. Jim continued his political campaign while supporting his family through his farm on Seaside Plantation. John, being a business man by trade, supported the community through economic pursuits. Both men organized cooperative land purchase agreements on Edisto Island to secure land for freedmen.

The site of the Hutchinson House was purchased by a cooperative organized by Jim to purchase all 404 acres of Shell House plantation. The land, once purchased, was divided among the contributors to the agreement according to the amount they contributed. Jim Hutchinson secured 74 acres of highland and 90 acres of marshland, including Clark Manor and all its outbuildings, from the purchase in 1875. Other members of the cooperative, each having received between 10 and 20 acres of unimproved land, had their doubts on the fairness of this deal and a lawsuit was levied against James Hutchinson. The suit was long and drawn out; Jim’s murder in 1885 complicated it further. Eventually, the suit was settled and the Hutchinsons retained all of their lands. Jim’s son, Henry Hutchinson, inherited the tracts where Clark Manor still stood and where he had finished building his home.

Henry Hutchinson began building his home after his marriage to Rosa Swinton and completed it around his father’s death in 1885. Located adjacent to Clark Manor on a shallow ridge, the elevated two-story building was ideally located to catch the breeze of Ocella Creek and access the road to Point of Pines. Once his home was complete, Henry refurbished the cotton gin house next door. By 1900 Henry had become a successful Sea Island Cotton planter. He made a name for himself in Charleston through his early maturing, high quality Sea Island Cotton that he sold to his factor Dill, Ball, & Co. Henry became a pillar of his community by operating a local cotton gin and offering loans to neighbors to purchase farming necessities. By ginning cotton for his fellow freedmen and acting as a middleman to sell their baled cotton directly to his factor in Charleston, Henry was able to circumvent many of the economic prejudices his fellow freedmen farmers faced in the cotton market. This secured them a better price per pound of cotton and the extra volume of product allowed Henry to work directly with a factor to receive investment capital and agricultural loans. The crop that had once trapped them into slavery was now their means of means of economic sovereignty. Henry also grew vegetable crops for his family to eat and raised both cattle and chickens.

As Henry entered his 60s the Boll Weevil entered Edisto Island. With it came the decimation of Sea Island Cotton harvests for decades to come. No longer profitable to grow, farmers abandoned cotton to pursue truck cropping and livestock. Henry continued to grow Sea Island Cotton, if only as an ornamental, into the 1930s. Henry passed away in 1941 and Rosa in 1949. With Rosa’s passing, their daughter, Lula, inherited the land. Lula Hutchinson Whaley was a school teacher at Larimer High School on Edisto Island. Lula raised her family in her parent’s home and cared for many a grandchild under its roof. She planted the bulb-flower gardens and the fruit and nut trees that surround the house to this day.

The land and home passed through the hands of several Hutchinson heirs after Lula before it eventually found itself for sale on the open market in 2016. A community wide push was made to purchase the property to preserve the home. The Edisto Island Open Land Trust stepped up as the organization to purchase the home and secured a short term loan to buy the 9 acre parcel. Through fundraising we were able to pay off the loan by the end of the following year. With the financial assistance of the Charleston County Greenbelt Program, EIOLT was able to purchase the adjacent 9 acre parcel in 2019 to buffer the home from residential development. Now the Edisto Island Open Land Trust owns the home and the land it sits on with the goal of restoring the home, interpreting the history of the land, and building a community driven public greenspace for Edisto Island.