This week for Flora and Fauna Friday, it’s a departure from the norm to talk more generally about an ecological concept, and to highlight some foreign flora and fauna. Today you’re getting a crash course on the major Invasive Species of the South Carolina Lowcountry.

I’ve been writing this series for nearly seven years now and, if you’re a loyal reader, you may have noticed that I tend to look at practically all aspects of our Lowcountry ecosystems with an air of positivity and reverence, bordering occasionally on unfeigned evangelism. I tend to take the side of the scorned and maligned members of our natural world. The vipers, sandburs, spiders, coyotes, thistles, and even the rats; I’ve praised them all and preached of their importance.

Today’s subject is different. There are a select few species that have wrought my utter contempt. Beings so wretched and vile they deserve no safe harbor in this landscape. Invaders from exotic lands who undermine the foundation, tarnish the beauty, and corrupt the sanctity of this Sea Island we’ve toiled so hard to conserve. I’m speaking of invasive species, both plant and animal. Insidious and existential threats to the ecological integrity of Edisto Island and the whole of the Lowcountry.

First, let’s define what an invasive species is. An invasive species is an introduced exotic organism that has a measurable, harmful, damaging impact on native species and, by extension, the natural ecosystem which it invades. To expound upon this we have to also detail what an invasive species is not. Firstly, a native species cannot be invasive within its natural range. This generally extends to “Range Changers” which are native species that expand their range into a new area due to favorable changes in the landscape, for example Coyotes and Cattle Egrets. An “exotic” species is simply an organism native to someplace else, which now exists in a place where it never naturally occurred. Further, not all exotic species are harmful or damaging. An exotic species that establishes in a new area but doesn’t cause any meaningful harm is referred to as a “naturalized” species. So it’s only when things end up where they’re not supposed to be AND when everything else starts to go wrong as a consequence that an “invasive species” manifests.

But, before we continue, it’s important to note that an invasive species is not invasive in its own native range. It has a home where it belongs and where it plays an important role in its natural ecosystem. There, they also have predators and pests that keep them in check and competing species to level the playing field. It’s only when they’re introduced as an exotic in a foreign land that they become freed from these natural biological controls and can usher in an ecological plague.

Out of all the invasive species that occur in the South Carolina Lowcountry, of which there are well over a hundred, there are three plants and two animals that come to my mind as the worst of the worst. These five have precipitated unfathomable ecological destruction and economic burdens throughout the Southeast: Chinese Privet (Ligustrum sinense), Feral Hogs (Sus scrofa), Chinese Tallow Tree (Triadica sebifera), the Red Imported Fire Ant (Solenopsis invicta), and Common Reed (Phragmites australis).

Chinese Privet (Ligustrum sinense) is the poster child for invasive plants, a wanted poster that is. Chinese Privet was introduced to the United States in the mid-1800s. It has opposite, evergreen leaves and showy clusters of white, spring-blooming, fragrant flowers. As such, it was planted widely as an ornamental shrub. However, following the Civil War, many agricultural fields were laid fallow and Chinese Privet began leaching out into the Southern landscape. Its dark blue-purple drupes in summer are attractive to birds, who gorge themselves before flying off, spreading the seeds as they go. Chinese Privet can grow on a wide array of soils, tolerates full sun and partial-shade, spreads clonally, and is evergreen with a dense canopy. These characteristics create the crux of what makes it so terrible. Once established on a field row or roadside, it begins a generational march into the forest understory, creating an impenetrable privet thicket that slowly snuffs out all plant life below it. When a tree falls and light hits the forest floor, it creates a pocket of prime songbird habitat, which Privet then exploits. The birds unknowingly hop-scotch the Privet into these clearings, allowing it to advance its front with ease. Soon the Privet saturates the forest floor and withers away the surrounding biodiversity. Privet is an over-bearing threat in the upstate of South Carolina. Here on Edisto Island, we have a fair bit of privet but, thankfully, it is mainly kept in check by our native Sea Island flora. Our native trees and shrubs often grow fast enough and thick enough to freeze Privet in its tracks before it can spread. Yet, it often still secures a foothold in fallow fields and around human developments. A quick tangent, many of our invasive plants here in South Carolina originate from China or Japan. This is not a coincidence. Certain regions of Japan and especially coastal China have a very similar climate and soils to the Southeast. So, when brought here, their plants grow equally as well, but without the other species that naturally control them.

Feral Hogs (Sus scrofa) are a special kind of blight. They look like a typical pig, albeit more athletic and hairier, because that’s all they are. Feral Hogs are descendants of domesticated pigs, gone feral. Their ancestors escaped from captivity centuries ago and returned to life in the forest. Just the wrong forests on the wrong side of the ocean. Although they’re fully feral, they’ve retained all those traits that make pigs a versatile and adaptable livestock. Feral Hogs can reproduce at an astonishing rate, with sows able to breed at less than a year old and capable of raising 15 or more piglets a year. Under ideal conditions, a Feral Hog population can more than quadruple in a year. Hogs are unbelievably intelligent, being smarter than most dog breeds, and they learn how to evade people, defeat barriers, and avoid traps rapidly. They’re also big, tough, and fast. Weighing over 100 pounds, not much can threaten a full grown sow. Full grown, a boar can exceed 200 pounds and wields a face full of pointed tusks. Hogs, especially boars, can be aggressive and a deadly threat to people and pets. A Hog’s nose is incredibly sensitive to both smell and touch, letting it find food buried underground. Yet it is also strong enough to function like a plow and is capable of upturning the most hard-packed soils and digging under fences. Hogs will eat anything and everything, and I mean that. They are true omnivores and will eat plants, tubers, seeds, nuts, insects, reptiles, fresh carrion, bird and sea turtle eggs, and any mammal or bird they can catch. All these factors combine to make Feral Hogs, by no exaggeration, an existential threat to the conservation of many rare and endangered species in the South. Feral Hogs can single-handedly decimate native plant and wildlife population, and may even extirpate them from the landscape. They destroy farmer’s crops at every chance they get and pollute waterways by upturning, wallowing, and defecating in creeks and wetlands. Their constant digging and eating of native plants plows and primes the soil for invasive plant species to set seed and take root, further destroying an ecosystem. Wherever they go, Feral Hogs wreak havoc and bring destruction. The only silver lining to this blight is that they are at least made of bacon! There are ostensibly no harvest limits or hunting restrictions on Feral Hogs in South Carolina. This is to encourage continuous and relentless population control. However, a sickening trend has developed nationwide, some people have deliberately spread Feral Hogs to new counties and states in order to create sport hunting opportunities. This is a highly illegal and a morally bankrupt practice, but still it continues to spread Feral Hogs within the United States. We are extraordinarily blessed on Edisto Island to not have any established populations of Feral Hogs. However, Hogs do occasionally swim across the South Edisto River. Thankfully, so far, they have been kept off our Island by our responsible local landowners.

Chinese Tallow Tree (Triadica sebifera), or perhaps more widely known as Popcorn Tree, is in my opinion the most destructive invasive plant established on Edisto Island. It has alternate, diamond-shaped leaves, white seedy fruits, and a pale-gray lightly flakey bark. Chinese Tallow was first introduced to the United States in the late 1700s for soap making but later became a popular ornamental tree due to its colorful fall foliage and large white seeds. It is well adapted to growing in coastal wetlands and tolerates shade, full sun, well drained soils, saturated soils, and even occasional saltwater flooding. Once established, Chinese Tallow grows unimpeded, as its foliage is toxic to herbivores. It grows quickly into a small tree and can begin to produce seeds when it is only a few years old. Its seeds are coated in a thick wax, which gives them their characteristic white color and the “popcorn” common name. This wax is an attractive food to many birds, including bluebirds, woodpeckers, and cardinals. They swallow the seeds whole, digest the wax, and pass the seed some time later somewhere else. This disperses Chinese Tallow seeds far and wide. At the same time, seeds that aren’t eaten fall to the ground in winter. Our Lowcountry wetlands are often flooded in winter and these seeds float, allowing them to disperse by wind and floodwater to distant shores. Some seeds inevitably germinate below the parent tree as well. These two dispersal mechanisms result in Chinese Tallow taking root in every inaccessible corner of an intact wetland in as little as five years. That’s when the real problems start. Chinese Tallow is an ecosystem engineer, one that engineers the subversion and destruction of healthy wetland ecosystems. Once established in a wetland, its seeds can lay dormant in the soil. All it takes is one disturbance event, like a flood, a drought, a fire, or salt intrusion, to activate these seeds like sleeper agents, which quickly grow into full blown trees. Each one of these trees acts like a water pump that sucks water from the wetland soils and evaporates it into the atmosphere. This upsets the balance of the wetland, which allows for more Chinese Tallow seeds to germinate. This creates a positive feedback loop where Chinese Tallow starves the native wetland plants for water and then takes their place the following year. This eventually creates a nearly pure stand of nothing but Chinese Tallow, which then wrests control over the wetland’s hydrology. Eventually, if the soil dries out enough, upland plants may try to intrude. The upland plants shade out the tallow and the Tallow stops pumping water, which causes the wetland to flood, which kills the intruding upland plants, which allows the Tallow to repopulate. It is truly a diabolical strategy, a vicious cycle by design.

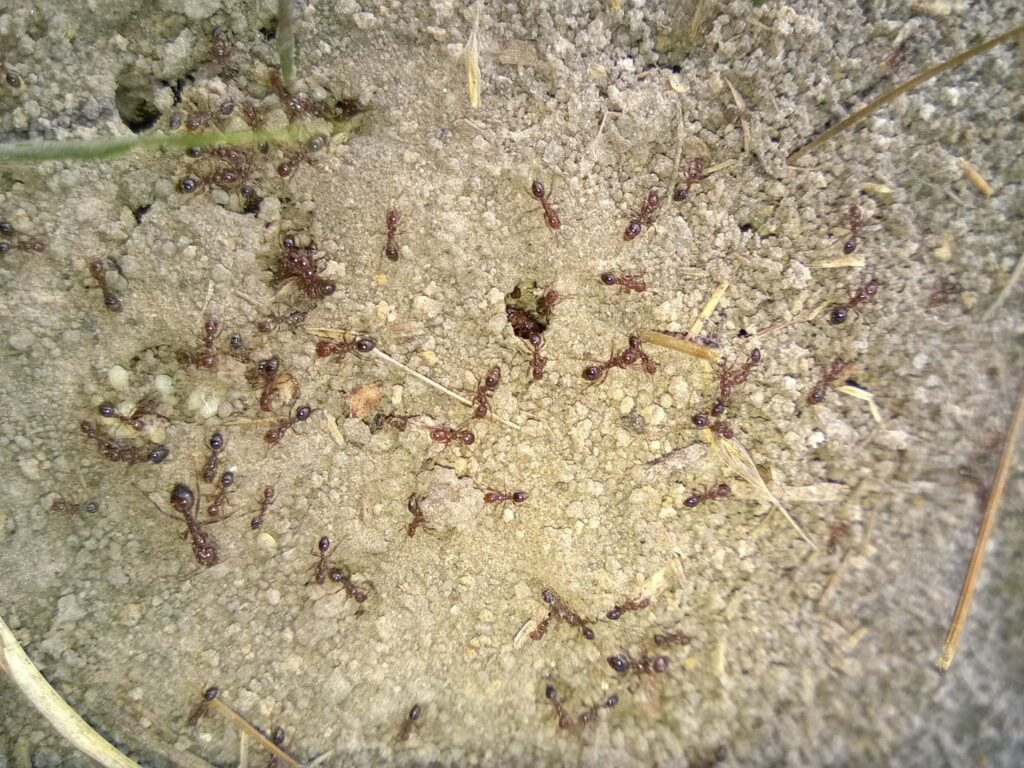

Red Imported Fire Ants (Solenopsis invicta) are small ants with a dark-red head and thorax and a darker-red or black abdomen. They build large, porous mounds with a sponge-like appearance and no central entrance. Fire Ants are likely the single most destructive invasive animal to southeastern wildlife biodiversity, even more so than Feral Hogs. The difference between these two invasive animals is that Hog damage is often isolated and is impossible for any land manager to miss. Fire Ant damage is omnipresent and insidiously hidden. Red Imported Fire Ants were unintentionally introduced into the United States in about 1920. These ants have then spread like a fire across the United States since and can be found in every corner of South Carolina. The full extent of the ecological damage that has been caused by Fire Ants is almost impossible to quantify or gauge. Fire Ants eat practically any animal they can reach and they can live in practically all habitats from fields to savannas, from forests to beaches, from parking lots to even rice field marshes. Over the last century they have systematically invaded every corner of South Carolina and secretly waged an unyielding war of attrition on all fronts against our native wildlife. They’ve imperiled turtles, butterflies, quail, salamanders, bumblebees, snakes, bats, and even our native ants, nothing is safe from the onslaught of Fire Ants. What makes Fire Ants so particularly destructive is multi-fold. To start out with, unlike all our native ant species, they’re violently aggressive, attacking anything they encounter whether it be a threat, potential food, or a human foot just minding its own business. Our native wildlife have no adaptations to deal with these unprovoked swarm attacks. But fleeing does little good as Fire Ants are everywhere. Fire Ants have spread so far and wide because they’re adaptable, but also because of their teamwork. Normally, ant colonies fight with other neighboring ant colonies, even within their own species, over resources and territory. However, Red Imported Fire Ants colonized the United States through just a few isolated introductions. This has resulted in all the Fire Ants being one giant extended family, meaning they see each other not as enemies but as allies. The consequence is that all the Red Imported Fire Ants in the United States operate as one gargantuan, unstoppable supercolony which persists at unnaturally high colony densities and, like an out of control fire, slowly and surely consumes everything it envelopes. This unceasing horde of ants has decimated the populations of many ground nesting birds, turtles, endemic amphibians, pollinators, and native insects. Much of this destruction occurred rapidly and out of sight, before ecologists even knew it had begun. When wildlife populations plummet, it has ripple effects throughout an ecosystem. If there is a population decline in pollinators, herbivores, and/or seed dispersers, their decline can cause native plants to either suffer or grow out of control, creating a positive feedback loop known as a trophic cascade. These ecoregion-wide ecosystem changes caused by Red Imported Fire Ants have been ongoing for over a century now in some places, their scale and severity are so acute yet diffuse as to be nigh incalculable by ecologists.

Common Reed (Phragmites australis), better referred to as Phragmites, represents a threat like none other to the tidal marshes of the east coast. It is a tall wetland grass with bluish-green leaves, a thick cane-like stem, and a large plume-like seed head. Phragmites was introduced from Europe in the 1800s, assumedly by accident. Phragmites thrives in the brackish tidal wetlands of South Carolina where it can grow over fifteen-feet tall and spreads by rhizomes underground to form vast monocultures in our tidal wetlands. A monoculture is when only one species of plant grows in a specific area. This can be normal and healthy, as in the case of our Smooth Cordgrass saltmarsh, but more often than not it is the destructive consequence of an invasive species invading a natural habitat and being left unchecked. The latter is the case with Phragmites. Phragmites has characteristics unlike any of our native wetland grasses which give it an unnatural advantage in our coastal wetlands. Phragmites grows almost twice as tall as any of our native marsh grasses, allowing it to shade out its competition. It forms dense, evergreen thickets that, in addition to the shade, further prevent native plants from competing by raising the elevation of the marsh substrate. It can also tolerate fairly high salinity levels and dramatic tidal fluctuations, allowing it to establish on the margins of saltmarsh or within the brackish zones where native wetland plant populations are naturally unstable. These traits together give Phragmites the ability to elbow its way into even the healthiest of marsh ecosystems, where it runs amuck unfettered, smothering native marshes as it goes. These Phragmites marshes have a much lower species biodiversity and don’t support all the same endemic species that our native marshes nurture. Many of these species being already critically imperiled from habitat loss, over harvest, water quality degradation, and sea level rise. Phragmites also threatens managed tidal impoundments and historic rice fields, which many species of waterfowl and shorebirds depend upon within the Atlantic Flyway. On Edisto Island, the spread of Phragmites is sporadic and so far has been limited to impoundments and brackish systems along the Intracoastal Waterway, where ships and dredging machinery from out-of-state have shed hitchhiking seeds to be swept inland by the tides. Phragmites is not able to survive the full brunt of saltwater like Smooth Crodgrass can, but it certainly is trying to gain a foothold around Little Edisto and deeper into the heart of the ACE Basin. [Phragmites is not to be confused with Giant Cane (Arundo donax). Giant Cane is a very similar looking ornamental exotic that usually exceeds ten-feet in height and grows on moist uplands, rather than marshes. It can also be invasive, just not to the same degree nor in the same habitats.]

The truly insidious thing with these five invasive species is that there is currently nothing that we can do to thoroughly control them. They are all still ever spreading on the American landscape. All have been running rampant, mostly unchecked, for nearly a century or more but some have only truly unleashed havoc in the last 50 years. Once any one of them becomes truly entrenched, they’re practically impossible to stamp out. The only solutions to controlling them so far require expensive, continuous, active management just to keep their populations under control. If these efforts cease, the destruction would be unfathomable. This makes the idealistic concept of preserving ecosystems in their natural state (E.G. taking a hands off approach and letting nature take its course) now untenable in the Southeast. Right now, the damage done by the hands of man can only be staunched with the deliberate and desperate actions of those same hands. Taking a hands off approach with our natural landscapes today is tantamount to throwing what’s left over to the Hogs.

That’s also just the big 5. There are over a hundred more invasive species in South Carolina and more keep appearing with each passing year. Some have even made their debut in the State in our own backyard, for example the Asian Long-horned Beetle (Anoplophora glabripennis) outbreak in Hollywood, SC and the Cuban Bulrush (Oxycaryum cubense) invasion in Green Pond, SC.

However, all hope is not lost! The more people who recognize and rectify these existential environmental threats, the sooner we can snuff them out. Biologists are feverishly working on developing biological controls to wrangle these five pests into submission and one day these efforts will come to fruition. In the meantime, ecologists and land managers toil day in and day out to expunge invasive species from our natural landscapes. You too can play a vital role, especially when it comes to controlling invasive plants. Take a gander around your garden, your yard, your driveway, or your property. You might be surprised to find where invasive plants have already taken root. If they have, cut them down and dig them up. Then keep an eye out for when, not if, they return. If you don’t have land yourself, considering volunteer with SCDNR, USDA, EIOLT, or other local nonprofits on invasive species work days. On the other side of the coin, when you’re perusing plants at your favorite big box store or nursery, double check that that shrub you’re eyeing isn’t a Trojan horse. If we all do our part, if we plant native plants and root out invasive species, we can conserve and improve what we’ve still got left of the Lowcountry’s natural history.