This week for Flora and Fauna Friday we have the wick of the savanna, the tinder of the timberlands, the powder keg of the pineywoods, Threeawn (Aristida spp.), aka Wiregrass.

Here in South Carolina we have a little over a dozen species of Threeawn. In the Lowcountry, that number dips to about seven decently common species. Four of the dozen species I want to highlight: Southeastern Slimspike Threeawn (Aristida longespica), Arrowfeather Threeawn (Aristida purpurascens), Southern Wiregrass (Aristida beyrichiana), and Carolina Wiregrass (Aristida stricta).

Southeastern Slimspike Threeawn is the most common species of Threeawn you’ll find on Edisto Island. It’s an annual species that grows most often in sunny sand barrens and other dry clearings. It has a compact and skinny growth form, sparse flower stalks that reach upright to about knee height, relatively small seeds, and narrow leaf blades that curl when they dry. Arrowfeather Threeawn is the most widespread species statewide but not as abundant on the Sea Islands. It grows on deep sands and dry ridges in pineywoods, barrens, and savannas. It’s a perennial bunch grass with an upright form, dense flower stalks reaching up to about waste height, fairly large seeds, a burgundy-purple wash to its upper foliage, and blade-like leaves that curl as they dry. Southern Wiregrass and Carolina Wiregrass are a package deal. The two species were recently split and look quite similar. Carolina Wiregrass is found in the northern Sandhills of South Carolina down our eastern border to and through the coastal plain of North Carolina, but not in the Lowcountry. Southern Wiregrass, however, is found throughout the southern point of South Carolina, from the Francis Marion National Forest to Aiken and down through the savannas to the Savannah River. The two Wiregrasses reside in frequently burned Longleaf Pine savannas and grow on deep sands. They’re a perennial bunch grass that spreads clonally, grows as a dome of thin wiry leaves, and bears narrow but dense flower spikes which may reach up to hip height.

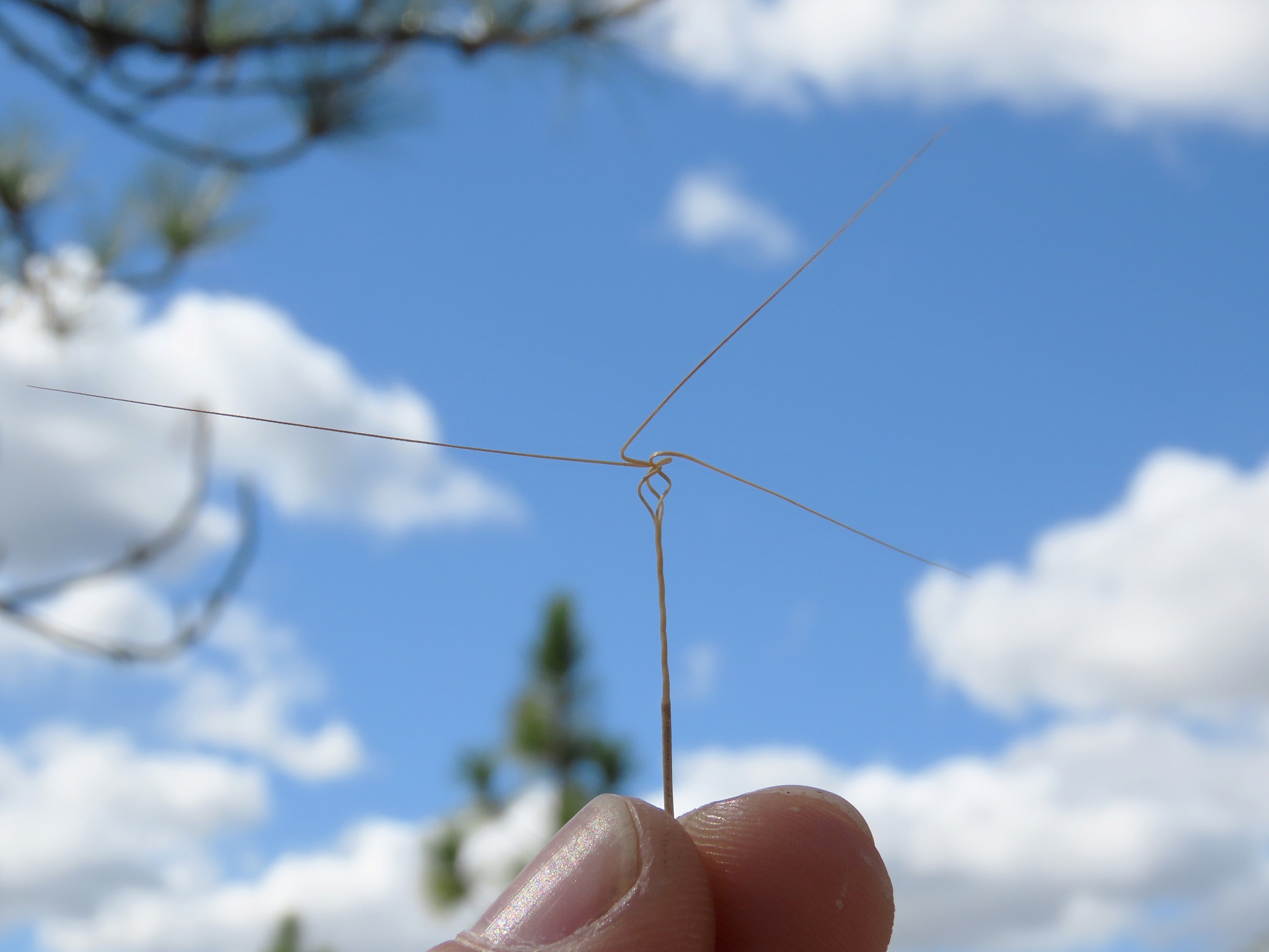

Threeawns are remarkable both physiologically and ecologically for their seeds and foliage. The seeds of Threeawns have three conspicuous awns. That’s where they get the common name. Awns are a long pointed projection of the leaf-like bracts that surround a grass’s flowers and often sheath the seeds. (Recall a head of wheat or barley. Those pointy bits are the awns.) The three awns of Threeawns are notable for twisting around each other, like a basket in a wrought fence, before then bending at a right angle. It’s a shape that’s hard to describe. Imagine an umbrella without the fabric and only three arms, but with a spiral twist in the middle. This twisted tripod of a seed has some innovative properties that enhance its chances of finding a good home. Firstly, that umbrella like shape helps the seed catch the wind and float further than it would just falling straight down. Although, they’re too heavy to float indefinitely. Second, the awns catch on the fur of passing mammals or pants legs of hikers, letting the seeds hitchhike to a new home. Saving the best for last, the awns are a compliant machine that operates as a drill fueled by humidity. These three awns are grown with an asymmetrical composition; one side of each wiry awn is denser than the other. When these awns dry, their difference in internal density causes one side to shrink more than the other, twisting and bending the base of the awns like a clock spring. When rain or heavy dew wets the seed, the awns absorb the water and stretch back out into their original straight shape. As sun dries the seeds, they twist back up. This acts on the same principal as an analog hygrometer, used to measure humidity. You can even grab a seed off a plant on a dry day, breathe heavily onto it, and watch the thing spin in your hand! This hydrated helical spin has an important function, drilling the seed into the soil. When the seed falls to the ground, the heavier seed side lands pointed down. If it’s lucky, it will land on bare soil, but it might be blocked by debris or duff. That’s when the drilling begins. Even in the driest of climes at the driest of times in the Lowcountry, our air is still sopping wet with water. That water condenses and drenches the ground as dew every night. Then, the scorching suns evaporates it all back into the air. This process repeats every day, spinning and shifting our little Threeawn seed. When the awns straighten, their tips anchor into the substrate as they twirl and push the seed forward, deeper towards the soil. When they dry and curl back up, the awns smoothly slide against the litter like a free spinning one-way ratchet, preserving the progress of the seed’s downward spiral. This cycle repeats daily, until the seed strikes pay dirt and sets roots in the sandy soil below. It’s a truly amazing adaptation!

Yet, spinning seeds ain’t the only trick this grass has hidden up its leaves. The foliage of Threeawns is built to burn. When old leaves dry, they do so thoroughly and then twist like a corkscrew together into a ball of tinder. This effect is most evident in the annual Slimspike Threeawn. However, both the Wiregrasses take this strategy to the extreme. Wiregrass is an ecosystem engineer. It combines its flammable foliage with its dome-like shape, its deep and expansive root system, and clonal nature to dominate the understory of the Southern Pine savanna. Hand in hand with Longleaf Pine it turns the forest floor of the pine savanna into a web of fuses, linking the ring of pitch plastered pine needles around each Longleaf Pine into a continuous carpet of fuel. The foliage of Southern Wiregrass in particular is so flammable, it will purportedly still burn in wet conditions. Through this smoldering smothering of the understory, Wiregrass fans the flames of renewal brought by natural and controlled fire. When Wiregrass’s prescription for fire is met, it is astounding how stable an ecosystem Longleaf Pine and Wiregrass have forged, its beauty jaw-dropping and biodiversity awe-inspiring. I’ve even read research suggesting the mycorrhizal fungi living in the sands of these fire-ravaged lands have a third hand in the conspiracy for conflagration, supporting the growth of the pyrophytic plants, promoting the flammability of their duff, and suppressing fire-phobic plants and fungi. The interwoven complexity of the southern pine savanna is an intoxicating realm to ecologists, extending above the pine boughs and below the tortoise burrows with a breadth wider than the Wiregrass roots that tie it all together.

If you’d like to get a gander up close at the glory of our southern pine savannas, SCDNR’s brand new Coosawhatchie Heritage Preserve in Yemassee, SC is a prime site to see a proper Wiregrass savanna. Or if you ever find yourself upstate cruising down HWY-1 through McBee, SC, Carolina Sandhills NWR is unforgettable detour!